We gathered in the frigid pre-dawn hours, our gear and luggage piled in front of the snowmobiles and our noses freezing in the -22ºF (-30ºC) temperatures. It was time to be saying good bye to our Russian hosts after a week of diving the frozen White Sea but we were tempted to linger just a little bit longer. It was during these last few moments, as we stood under a curtain of stars on a deep, dark winter’s night in Russia that we reflected back on the events of the past week.

Story and Photos by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher P. Weaver

We had come to this remote spot a week earlier filled with both excitement and anxiety over the prospects of exploring the icy waters of the White Sea. Nestled alongside the Kola Peninsula, and straddling the Arctic Circle, the White Sea, technically part of the Barents Sea, is the only inland sea to completely freeze in the winter. Our base of operations for this ice-diving expedition was the Arctic Circle Dive Lodge, located near the seaside village of Nilma and just north of the Arctic Circle. To get here, we chose to fly to Finland, arriving in the alpine town of Kuusamo. After spending one day dog-sledding in a National Forest in Finland’s fabled Lapland, it was time to complete our journey with an over land transit into Russia.

An 8-hour white knuckle ride across the border and through the Russian wilderness brought us to the lodge, ready to dive.

Diving the White Sea in winter requires preparation, equipment, fortitude and, most important adequate training in ice diving techniques. Please note, divers will not be permitted to dive unless they are ice certified by a recognized training center like PADI. However, for those divers who are not ice certified, the Arctic Circle Dive Lodge does offer an ice certification course that can be taken during their stay. With surface temperatures routinely dipping as low as -22ºF (-30ºC), and with snowfall an almost constant factor, divers must be prepared for extreme conditions. The entire White Sea is frozen with almost 3 feet of ice and the ice is covered with six inches or more of snow. Once below the ice, divers will find water temperatures hovering near 28ºF (-2ºC). Although visibility is generally good, the water can be extremely dark. Many of these dives can almost be considered night dives due to the lack of ambient light penetrating the snow covered ice ceiling. Fully functioning cold-water gear and good training are essential.

Indeed, divers must come equipped with well-tested dry suits complete with adequate thermal protection capable of withstanding near 28ºF (-2ºC) temperatures. For our dives in this region, we used an integrated glove system that permits a constant exchange of warm air over the hands during the dives. Beneath the dry suits, we employed a layering system to fend off the extreme cold. A thin base layer of wicking material worked in conjunction with a warming fleece layer and was topped with heavy-duty dry suit underwear. Since a lot of heat escapes from the head and feet, we also chose to dive with ice caps beneath our dry hoods and at least two pairs of thick thermo-type socks. Environmentally sealed regulators are a must to reduce the likelihood of free-flow from freezing temperatures and ice crystals inside the regulators.

The diving protocol employed here provides everything necessary to protect divers from the elements. Divers and gear are first transported from the lodge to the dive sites via snowmobile. The dive sites vary and can be as close as a 10-minute run or as far as a 45-minute trek across the ice covered sea. Once on site, specially constructed small wooden huts are used as shelters for donning on doffing equipment. Each hut is equipped with a wood burning heating system so divers can gain much needed warmth before, between and after dives. Indeed, the temperatures inside the huts are almost too hot and divers will often be seen propping the doors open to let in some cool air!

The huts are on skis and can be moved from location to location. They are generally placed within a few feet of the dive site, usually a triangular cut made into the ice and referred to locally as a “Maina”. Once suited up, divers shuffle to the entrance and begin the icy plunge into the magical world beneath the frozen sea.

Our first dives in the White Sea took us to a site known as “Anemone Rock”. Here, in 45 FSW (14m), a huge boulder lies on the bottom, perhaps 20ft (6m) in height. This rocky outcrop rises up from the slope of Bolshoy Krestovy (Big Cross) Island. Some say it is as big as a three-story building and shaped like a dragon’s tooth. The seabed is very silty, so care must be taken so as not to stir up the bottom. Otherwise you will raise a tremendous cloud of sediment!

Anemone Rock is so named because of the profusion of life that literally covers this massive structure. Frilled Anemones, colorful tunicates, beguiling nudibranchs and a wide variety of other small invertebrate life abound on this oasis of life in an otherwise nondescript sloping bottom. Wedged inside cracks in the rock are Wolf Fish, expertly positioned to avoid the range of our cameras! Looking more closely alongside the rock, we did find small bottom dwelling fish such as the Arctic Sculpin. Measuring close to 4 inches (10cm) in length, these wary denizens seemed unfazed by our attempts to photograph them…perhaps they were too cold to move!

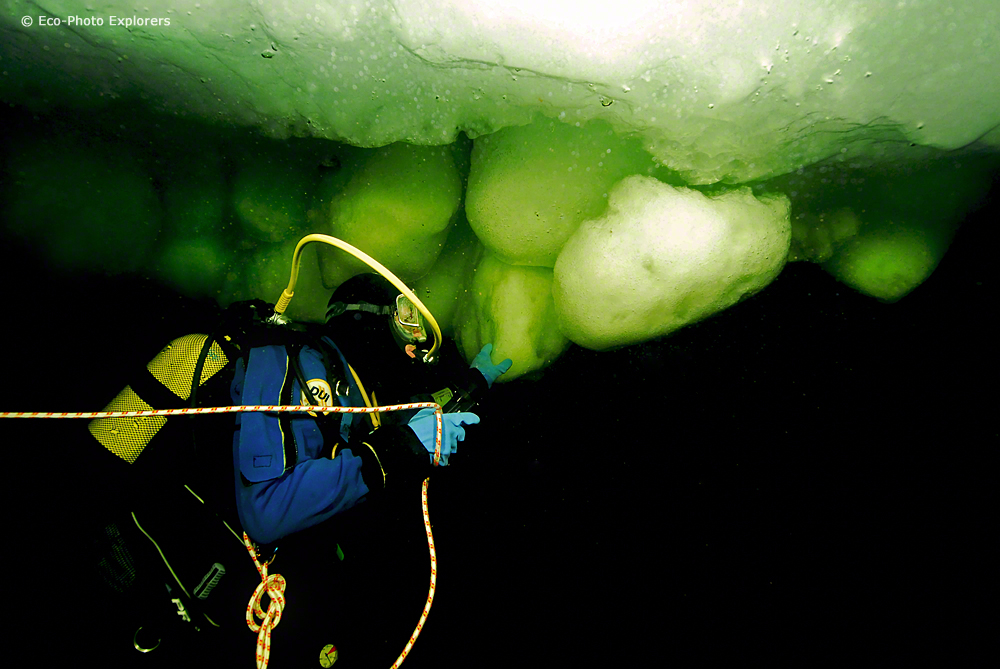

Subsequent dives took us to dive sites alongside some of the islands in the White Sea. Small Cross Island is a small rocky outcropping with a tumbling, rocky slope, which we eagerly explored, photographing the kelp (laminaria) covered rocks and the dramatic ice ceiling above. Diving beneath the ice affords the diver an out-of-this-world experience as the surface ice takes on a greenish tint from the surrounding water.

Typically, our dive days consisted of a maximum of two dives. The extreme cold coupled with the rigors of diving under the ice makes more than two dives impractical and physically difficult. Each dive would last about 30-40 minutes before we would begin to lose dexterity on our hands and begin to suffer the chilling effects of the cold throughout our body.

Photography in these conditions is especially challenging. Besides the crippling cold, we struggled with an absence of light in the otherwise clear water column and careful attention to exposure and lighting was a constant necessity. In addition, the chilled water sapped the energy from the batteries in our camera systems. Each evening, our room was strewn with battery chargers working hard to breathe life back into our stressed camera system batteries. The equipment functioned properly for the most part, but there were times when the electronics began to fail in unpredictable ways. Replacing your camera system with fresh batteries before each dive and keeping them in a warm place before use is key! The adventure and challenge of diving in this frozen sea extended beyond our physical abilities to the constant care and feeding of our camera systems!

Towards the end of our week’s expedition, the temperatures plummeted from a rather comfortable 20ºF (-7ºC), to a bone-chilling -22ºF (-30ºC). Suddenly, our dives became more arduous as we struggled to stay warm and keep our equipment functioning. Residual water would freeze instantly in the air and our equipment became encased in ice in a matter of minutes. The entrance to the dive site would become a slushy mix of ice and snow, and any water exposed through the hole would also start to quickly freeze solid. As we descended through a 2-foot (.6m), tunnel of slush and ice, it took all of our self-control not to breathe off the regulators until fully submerged lest we risk causing a free flow. And once under the ice we preferred not to think too hard about whether the surface tenders were keeping the hole cleared of solid ice!

At Biofilter Bay, a location named for its abundance of shellfish and filter feeders covering its rocky bottom, we descended into a cathedral of ice. Biofilter Bay is nothing extraordinary in summer, but it completely changes in winter. The most interesting thing about ice diving here is the ice itself. Because of the strong tidal currents, the high and low water levels differ by up to 6ft (2 m), and the tidal cycle lasts about 12 hours. As the ice rises and falls within the water column, it freezes to the rock faces and other ice formations. It then breaks off and tumbles around bumping into each other, then freezes again to these surfaces. This constant tumbling and moving about allows the ice to carve amazing underwater ice sculptures.

As we drifted along the sloping shoreline just under the ice ceiling, we were able witness and explore these chaotic jumbles of fragmented ice crushed together in magnificently sublime formations. Huge slabs of ice along with bulbous ice boulders floated in the frozen sea, and as we swam in and around these icy monuments to nature’s true beauty and power, we became reflective of how special this place really is. With only our line to lead us back to the opening and to the spine tingling cold of the world above, we were truly encapsulated in the silence of the frozen ice spectacle below. We floated among these grand ice displays, becoming one with its frozen beauty before reluctantly returning to the entry hole and the surface.

Beneath the White Sea, in the mysterious and seldom visited Russian Arctic, we had experienced moments of true physical hardship along with experiences of fabulous and magnificent beauty. And now, as we stood in the bitter cold waiting for our transport back to Finland, we swapped stories and reflected on our experiences. Suddenly, as if on cue, a shout rang out in the night:

“Aurora!”

We all excitedly scrambled back to the edge of the frozen sea, our feet standing in newly frozen snow, and we looked up to the sky. There, a shimmering, undulating miracle of nature was being displayed across the night sky…the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights)! The script could not have been written more perfectly…it was as if we were being bid farewell by the Arctic itself. With brilliant greens and yellows, the Aurora danced for us as we departed…a dance of indescribable beauty that has beguiled people for millennia in the northern latitudes. And one that will continue for millennia to come.

White Sea Information

- Dive Time: Usually 20-45 minutes, diver dependant

- Breathing Gas: Air; Nitrox is not available. Argon gas for dry suits is not available.

- Depth: Rope dependant; usually not more than about 65ft (20m)

- Water Visibility: 50-150ft (15-50m)

- Ice Thickness: up to 5ft (1.5m)

- Water temperature: 30-28°F (-1°C to -2°C)

- Air temperature: 43°F to -22°F (+6°C to -30°C)

- Salinity: 27.5–28 parts per thousand, lower than the mean salinity of the Arctic Ocean

- Heated huts are available for divers to don/duff gear, and to relax between dives

- Snowmobiles are used to transport divers and equipment to and from the dive sites

- Diver tenders help divers exit the dive hole, ladders are not used

White Sea Expeditions

http://ecophotoexplorers.com/whitesea.asp

Photo Gallery (Please click on an image to see a larger version):

- The spectacular Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis). Nikon D200, 18mm, f5.6, 30sec

- Author (Chris Weaver) prepares to dive beneath the ice.

- Authors (Chris Weaver, Mike Salvarezza) prepare to take the icy plunge under in the White Sea.

- Authors (Chris Weaver, Mike Salvarezza) prepare to enter the Maina, or ice hole.

- Siberian Huskies are hardy dogs well suited for the arctic environment.

- Dive tank filling station at the White Sea Base Camp.

- Diver exiting through the hole in the ice surface.

- Dive team on the way to the dive site across the frozen surface of the White Sea.

- Divers enter and exit through the hole in the ice surface.

- The ice formations of Biofilter bay are extraordinary.

- Divers are secured to the surface using a system of ropes.

- Divers explore the ice formations of Biofilter Bay.

- Beautiful ice formations mark the dive sites at Biofilter bay.

- Ice diver in the White Sea.

- An Arctic Sculpin warily eyes the photographer.

- Starfish can be found beneath the ice.

- Anemone beneath the ice.

- Snowmobiles are used to go from base camp to the dive sites.

- The dog sled team is led by Siberian Huskies.