My diving compadres and I were sitting around one evening slurping down Cadillac margaritas after a great day at the islands, and I was rattling on about a book I’d just finished called Diary of a Sea Captains Wife, by Margaret H. Eaton, et al. Besides the interesting concept that the town of Santa Barbara, on the California coast, had too much “hustle and bustle” to live in during the early part of the 20th century; the descriptions of variety and fecundity of marine life surrounding the offshore islands were truly astounding.

Words & Photos by Joseph C. Dovala

The isles reside within what’s known as the California Bight (pronounced bite). This isn’t the price of Golden State real estate, but rather a natural occurring missing chunk of land. If you look at a map of California it appears as if a giant took a big mouthful out of the southern coastline and then left behind a few crumbs. This indentation in the seashore provides a very different environment than if the coast continued straight down toward Mexico. The “crumbs” of islands and rocks sit within this bight and owe much of their richness to this geological feature. These land masses include, Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel, and Santa Barbara Islands. It also encompasses Richardson and Wilson Rocks as well. Collectively there’re known as the California Northern Channel Islands.

During the last ice age geologists surmise that all these islands were linked up into one large mass called Santarosae. The giant island was still not connected to the mainland, so this allowed for some unique animal and plant life to evolve. There was even a dwarf mammoth that happily munched away in the pine and cypress forests. After the great ice sheets melted the islands became separated with many creating their own versions of Santarosae flora and fauna. San Miguel and Santa Rosa Islands sit the farthest out primarily bathed in the nutrient rich colder California Current flowing from the north. Santa Cruz and Anacapa are closer to the mainland awash in the Davidson Countercurrent from the south. This confluence of two quite different water masses, along with seasonal upwelling, accounts for the large variety of marine life found here. Everything from gobies to the Blue whale plies these seas.

Human habitation in the Channel Islands has now been pushed back more than 12,000 years. A number of diverse Native American Chumash villages had been established on several of the islands, while others were used for gathering and hunting. The first Europeans, under Juan Cabrillo, showed up in 1542. With the huge influx of fur traders, sealers, fishermen, and others, the peaceful Chumash were “displaced”. By the early 1800’s, most of the Native Americans on the islands had either been wiped out or vacated to the mainland.

After the hunters decimated the local animal populations, sizeable sections were turned into ranches. Most of the heavy ecological damage occurred during this time from grazing farm animals. Several large full time ranches were in operation for many years, the last of which didn’t end until 1984. Promoted to a National Park from a Monument in 1980, nearly a quarter of a million acres came under limited protection. Over the past two decades significant progress has been made in restoring endemic environments as well as reintroducing nearly extinct island flora and fauna.

Only twelve miles from Channel Islands and Ventura Harbors, four mile long Anacapa Island (actually three islets) sees everything from kayakers and jet skis to mega yachts filming porn on their decks. The name Anacapa comes from the Chumash name of Ennepah, which means mirage. Aptly named, for it can appear quite different one day to the next depending on atmospheric conditions. The half mile wide land mass was never permanently occupied by the Native Americans because of lack of fresh water. It is a very popular diving destination due to the short travel distance. Also, there is little runoff so visibility tends to be better than at other islands. Anacapa has been hit pretty hard by excessive overuse but there are still some very nice dives to be had in a number of sites around the island.

Words & Photos by Joseph C. Dovala

Visit Joe’s website at www.jcdovala.com

There is a marine reserve on the eastern section but the more exciting immersions usually are off the western tip. Nearly always bathed in currents, you can expect lots of bigger critter sightings. Giant black sea bass, lots of sea lions, occasional sharks, and larger schools of blacksmith are typical. This area is for experienced divers only and commercial dive boats only rarely make a stop here depending on conditions. A little farther to the east is a place called Coral Reef. Obviously there isn’t a coral reef but the rocky environment can be quite colorful with a variety of invertebrates. At times kelp is fairly thick which attracts large schools of mackerel and blacksmith.

There are a number of sunken wrecks too. They’re quite old and flattened out but they have quite a story to tell. One ship, the Winfield Scott, a wooden three-masted side-wheel steamship, sank in 1853 in a mere thirty feet of water. Loaded with gold coins the “Winnie” has been a popular place to fan sand. Some of these coins found there way into collections ashore. Of course, today the site is protected and no salvage whatsoever is allowed. There is little left and it’s quite easy to swim right over the wreck site and not know it. After a good storm however, square copper nails, fittings, and an occasional shiny bobble are exposed.

The largest of the Channel Islands is Santa Cruz. At twenty-two miles long and up to six miles wide it was home to a sizable permanent Chumash population. The largest rancheros were also on this island. There are many different diving environments and you can experience colder temperate conditions practically right next to warmer sub-tropical environs. One such area is called Yellow Banks. There are often large kelp beds that stretch along this part of the island. Closer to shore typically has giant brown kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera). Once you get in deeper water, say around 80-90 feet, you can find large expanses of bull whip kelp (Nereocystis leutkeana). This alga needs colder current rich water, and you can expect bottom temps to be 4-8 degrees lower than closer to shore. This area is prime for drift diving.

Close to the island are sites such as Drop-Off-Reef and Little Scorpions. One interesting ship wreck is that of the Peacock, located in Little Scorpian Anchorage. The history is quite spotty and the sinking is some what of a mystery. She probably was sunk on purpose in 1979 for unknown reasons. The Peacock started her career as a navy minesweeper during WWII; just like Jacques Cousteau’s Calypso. Over the decades the vessel had many owners and one of the stories is she ended up as an offshore “boat of ill repute;” servicing gentlemen at sea. As it turns out no one knows the full story but the old wood wreck makes an interesting dive. It now resides within a no-take reserve so the fish life is becoming interesting again. Up the northwest side of the island is Painted Cave. This is a huge sea cave and some charter boat skippers will actually drive into it a short distance for a very interesting experience. It is more than 1,200 feet long and 100 feet wide at the opening. The water is around 60 feet deep at the mouth and the sheer rock walls are covered in strawberry anemones of various colors and hues. Actually diving inside the cave, or any sea cave for that matter, is very dangerous. Ocean surge is often funneled into the crevice and can then be magnified to disastrous proportions. Only the foolish venture inside sea caves without proper training and gear.

The next island out is Santa Rosa. At 10 miles wide and almost 15 miles long it’s the second largest of the Channel Islands. Kelp beds are extensive here and while dive sites are numerous, weather is often a deal breaker. Once you hit the far western end of Santa Cruz Island, sea conditions usually become much harsher. By the time you’re at Santa Rosa the prevailing northwest open ocean swells are bearing down unabated. This is not to say that you can never make a safe highly enjoyable sub surface visit, you just have to pay more attention to weather and sea conditions. And often, the dive charter boat sets off for Santa Rosa but you wake up somewhere on eastern Santa Cruz or Anacapa Islands.

Some very good dive sites include the East End Pinnacles and Johnson’s Lee. The Pinnacles, on a calm day, offer stunning underwater vistas with thick kelp growing on the tops of steep escarpments. Depth ranges here push 100 feet. Lots of fish congregate and the carpet of colorful anemones are quite abundant. This area is often bathed in currents -hence the fecundity of life – so the Pinnacles are the realm of the advanced diver. Johnson’s Lee is used as an overnight anchorage by charter boats and offers night diving and a shallower venue of reefs in contrast to the Pinnacles.

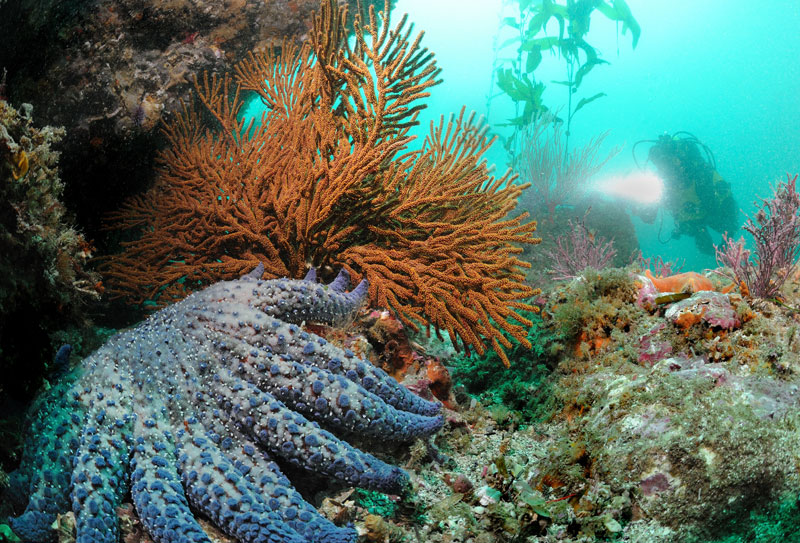

The western most of the islands in the archipelago is San Miguel. With only 800 feet of elevation, the eight mile long island takes the brunt of gales sweeping down from the north. Its windswept topography is a major haul out for sea lions, fur seals, and elephant seals. If Santa Rosa is tough to get to, San Miguel is downright arduous. If you can make it though, some of the best diving is actually around the partially exposed rocks nearby. Wilson’s Rock, located less than two miles to the northwest, has large populations of California hydrocoral (a true coral endemic to California). The walls and crevices are carpeted in colorful invertebrate life. Everything from anemones to nudibranchs to sea stars explode in vibrancy and diversity. Visibility can exceed 100 feet on a good day. Since there is essentially no bottom, good buoyancy control and attention to gas supply is the hard and fast rule to dive here. Richardson’s Rock sticks out quite a bit more than Wilson’s and actually qualifies as an islet. You’ll need to travel another six miles out in the open ocean, but if you can make it it’s like Wilson’s Rock on steroids. There have been reliable visibility reports exceeding 150 feet and the profusion of life is simply staggering. There’s even room for sea lions and Guadalupe fur seals to haul out occasionally. Even under the best conditions, diving usually doesn’t start until below 50 feet due to the effects of the oceanic swells meeting solid rock. Every square inch is covered with life and massive schools of pelagics sweep around the steep rock walls.

Back on San Miguel proper there are also some very good dive sites. One is Point Bennett Foul Area. An extremely large population of pinnepeds call this area home. The low lying reef supports many fish and invertebrates. Visibility is often quite good even in the 30 to 50 foot diving ranges. One last thought about San Miguel; with the abundance of marine mammals living on the island there have been more great white shark sightings here than any other Channel Island. The outer islands of San Rosa and San Miguel are not for the newly certified or inexperienced.

Over 50 miles southeast of Santa Cruz Island lies Santa Barbara Island. Though it is a good clip from the rest of the Channel Islands the one mile square land mass is part of the National Park. For its small size Santa Barbara Island has a huge variety in underwater terrain. There are kelp forests, archways, caves, small pinnacles, even very white sandy bottoms with numerous bat rays. The largest of the archways is called, appropriately enough, The Archway. It sits in about 80 feet of water and is festooned with gorgonians, anemones, and small clumps of hydro corals. Kelp grows heavily behind the arch and with the large assemblages of fish that often congregate; the whole vista looks like it was created for a giant public aquarium. On the opposite side of the island lies Southeast Reef. The large high relief area features small drop-offs, rocks, and ledges interspersed with sand corridors. There are also two smaller arches here as well. Bat rays and electric rays cruise the sand stretches, while moray eels thread through the rocks and sea lions play in the water column above. Southwest of the main island is Sutil Island, actually more of an islet. When conditions warrant, the caves, canyons, and walls make for lively and beautiful diving. There are few adequate over night anchorages at Santa Barbara Island so most visits are for the day only. This is the last of the offshore islands that are incorporated into the Channel Islands National Park. San Nicolas, Santa Catalina and San Clemente Islands to the south are not part of this park system.

The islands are not only worthy of visiting below the waves but topside too. All five allow visiting ashore. There are restrictions dependant on the island and sometimes the time of year. Anacapa and Santa Cruz have year round camping opportunities while the others have a season, typically April – November. All have great hiking prospects. Most have Park Rangers present at least part time.

A lot of years have passed since Diary of a Sea Captains Wife was written. And I highly doubt that Mrs. Eaton’s sea captain husband would find the current state of affair of his beloved isles acceptable. To be sure they have felt the sting of over use and effects of various polluting influences – and still do. In spite of everything though they are unique. The tremendous variety in marine life and topography is truly distinctive. It would be very hard indeed not to include a peaceful glide through the Northern Channel Island’s kelp forests as some of the finest diving in the world.

Words & Photos by Joseph C. Dovala

Visit Joe’s website at www.jcdovala.com