Photo by Parker H. House

Back in April 2011, my friend and I were diving off Casino Point on Santa Catalina Island in chilly waters when we looked up and saw four large black fish. They were about four to five feet long, cruising slowly in around 20 feet of water at the edge of the kelp. To my friend they looked like underwater cows; to me they seemed more like mellow hippies on floating motorcycles. Whatever they were, I was in awe of them. We were told they were giant sea bass (GSB), Stereolepis gigas, which return to the waters off Catalina Island every summer, and we were the first to see them that year.

Story by Mary Ann Wilson, photos as credited

These apex predators have had a rough time, being nearly fished to extinction until saved by legislation. Commercial fishing of giant sea bass began in Southern California in 1870 when fish were taken with hand lines. But as the take declined between 1915 and 1920, fishermen switched to gill nets, temporarily increasing catch. Commercial landings peaked in 1932 at 115 tonnes but then decreased rapidly. By 1935 most commercial fishing had shifted to Mexico. And by 1980 commercial landings in California waters had declined to 5 tonnes.

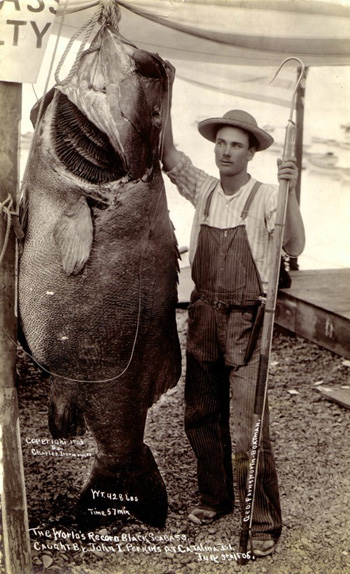

June 1906 world record at 428 lbs. Library of Congress, Digital Collections

In 1981, the California State Legislature banned commercial and recreational fishing for giant sea bass, but still allowed commercial fishermen to retain and sell two fish per trip if caught incidentally in a gill net or trammel net. This law also limited the amount of giant sea bass that could be taken in Mexican waters and landed in California. The law was amended in 1988, reducing the incidental take to one fish in California waters.

After the moratorium was enacted in 1981, catches decreased substantially. From 1983 to 1992, incidental catches remained low, ranging from 1.7 to 5.9 tonnes.

But the moratorium didn’t prohibit fishing over giant sea bass habitats where they could be caught incidentally. Entangled giant sea bass that would exceed the catch limit if landed were discarded at sea or distributed among fishing boats.

Other fish have also suffered from nets and overfishing. Soup fin sharks became scarce in the early 1940s, while leopard sharks declined in the mid-1980s. In a drastic move to save the fish, gill nets were banned as of 1994 from within three miles of southern California’s mainland. This regulation signaled a turning point for fish populations.

Dr. Larry Allen. Photo by Mary Ann Wilson

In a presentation given this past October, Dr. Larry Allen, biology department chair at CSUN, said the Proposition 132 ban on gill nets is what turned the tide for many commercially fished species. “We’ve seen a response of halibut, a response of giant sea bass that we’ve published, a response of leopard sharks and soup fin sharks and a variety of other large elasmobranchs which seem to have gotten some relief from commercial fishing.”

Dr. Allen worked for 20 years before seeing a juvenile giant sea bass in 1993. His first observation:

“Last year while trawling in Newport Bay on a sampling trip for Cal Fish and Game’s BENES program targeting local sport fishes, something memorable happened…Almost as soon as the trawl had hit the deck, my chief research assistant, Motz (Tom Grothues), began yelling something about a black sea bass. I was on the back deck in an instant grumbling in disbelief. I had never seen or heard of a black (or now, more properly, a giant) sea bass being taken from inside Newport Bay in all of my 20 years of experience there. But, sure enough, there it was. An absolutely gorgeous little fish about 6 inches long. It was reddish-bronze in color with jet-black circular spots and huge black fins…From the likes of this tiny, elegant fish — the largest, the eldest, and most magnificent of our nearshore fish species will emerge.” (Western Outdoors News, 1993)

He was right. A scientific monitoring program conducted quarterly by SCUBA divers with the Vantuna Research Group (see OceanBights Vol. 3, No 1) didn’t report any along Palos Verdes Point from 1974 to 2001. The giants were finally seen there from 2002–2004. That’s when Allen decided it was time to begin a study of giant sea bass. But his article entitled “The decline and recovery of four predatory fishes from the Southern California Bight” was turned down by Science, Nature and PNAS, because “there was one reviewer that simply didn’t believe our data. He thought we made it up,” Allen said. It was finally published 2008 in Marine Biology.

Giant sea bass swims by a Hydrophone. Photo by Parker H. House

Giant sea bass start life as brightly colored orange juveniles with large black spots, and ride the sand riffles in shallow water. According to Allen, the juveniles gorge on opossum shrimp, while the darker adults eat pretty much anything they want including fairly large spiny lobsters which they are more than capable of sucking out of their crevices with their large, gaping mouths. As the only “megacarnivore” inhabiting the kelp beds in southern California, they also consume Pacific mackerel, ocean whitefish, midshipmen, stingrays, white croakers, small sharks, crabs, and mantis shrimp.

Juvenile giant sea bass. Photo by Phil Garner

Historically, giant sea bass were distributed from Humboldt Bay to southern Baja California and the Sea of Cortez with populations concentrated south of Point Conception in shallow rocky reefs. According to Allen, the current primary range is Pt. Conception south to about Punta Abreojos, Baja Mexico and in the northern Gulf of California (north of the Midriff Islands). “We think they occur off the coastline of southern Baja California, but if they occur there, they are probably in deep water — say 200 to 400 feet,” Allen said. “We also think they or their larvae migrate around the tip of Baja joining the populations on either side of the peninsula, based on anecdotal and personal observations as well as genetic data.”

Very little is known about giant sea bass, but their increasing numbers enable better research on lifespan, size, mating and population diversity. In recent years, scientists have determined that the Stereolepis gigas are not even related to sea bass. They’re in a completely different group of fish, the wreckfish (Polyprionidae) which are very distantly related to groupers.

Photo by J.R. Clark

To estimate age, Allen counted the number of annuli on otoliths from 64 heads, obtained from the Santa Barbara Fish Market between January 2010 and May 2013. These fish were incidentally caught by fishermen working between the Northern Channel Islands and northern Baja Mexico. When he counts the rings he places a dot on each ring to ensure accuracy. Then he figures out how much bomb radiocarbon it has, and fits that into the calibration curve of bomb radiocarbon present in the Eastern Pacific. Bomb radiocarbon was produced from atmospheric nuclear testing in the 1950s and shows a very distinct pattern in most oceans, as the atmospheric fallout worked its way into the bony structures of all fishes and invertebrates. In 2012 Larry Allen and Allen Andrews were the first to validate annual growth rings for one individual and provide a verified maximum age, 76 years, for giant sea bass using bomb radiocarbon validating techniques.

Wild, live fish are being studied at Catalina. Two of Allen’s students, JR Clark and Parker House, received WIES Wrigley Institute Summer Graduate Fellowships and spent three months diving off Catalina Island, first locating the giants’ aggregations, then trying to determine their size, densities, and mating behavior. They also hope to learn what impact their return will have on kelp bed fish populations. Grants and $6,000 dollars in crowd funding help to pay for the students’ underwater hydro-acoustic equipment and sea scooters.

To find the minimum population size around the entire island, they chose eight sites: four where they thought they’d see giants and four where they thought they wouldn’t see them, and did the back side as well as front side. At one of these sites an aggregation of 24 was found.

To accurately size giants underwater, the students use length-calibrated lasers and a GoPro video camera mounted on top of SeaDoo SeaScooters. Two laser beams calibrated four inches apart are pointed directly (90 degrees broadside) at an individual fish so that the laser dots are visible in the video. Stills are later extracted from video and then measured using a software program. Using length to weight relationships, biomass is determined for different areas.

Photo by Parker H. House

Their calculated average biomass for the eight sites was 36.29kg/1000m2, which was higher than expected. House said this was due to the unexpected and very large aggregation at the Vee’s. The most individuals observed were 36 counted during the sampling period from July 15 to July 23, 2014. The least were seen during June with only nine individuals. The giants ranged from 0.9 to 2.7 meters while the majority were around 1.3 m (4.2 feet) in length. The International Game Fish Association all-tackle world record for this species is 563 pounds 8 ounces, caught at Anacapa Island in 1968. But the largest one seen this summer was 2.7 meters or 8.9 feet and weighed at least 325 kilograms or 800 lbs, and is the largest ever measured.

“It was relatively easy to count the individuals as many stayed in a general area,” House said. “Many of them have different characteristics; some had many parasites on their face, or scars on their fins or sides, or blotches so you can more easily identify one fish from another, although they do change color. Some would be near us and would show a certain color pattern, but once they moved away, you would see these patterns change. We think the changing of color pattern may be a signal for mating as well as communication to the other individuals.”

“Many fishes change color when they are ready to mate,” Clark added. “A good example is the kelp bass, which presents a yellow or orangey mask when males are in the spawning season. We have seen some color change, from a light to dark color type change. This has been previously described as a spawning type activity in giant sea bass.”

Another way to identify spawning and courting behaviors is by their sound. The students had just gotten down to one of their sites when they heard a BOOM — the sound of a very loud bass drum. “The first time I heard it I thought something was wrong with my tank,” House said. “So I checked my pressure gauge to see if it had dropped, but it wasn’t us. We looked around and a giant sea bass was coming straight to us, and then he checked us out and took off. We think the sound could be either a call to try and get us away because they were courting in that area, or to see if we were potential mates.”

![Clark_House[1]](https://californiadiver.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Clark_House1.jpg)

J.R. Clark and Parker House at work at the Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island.

The students use the sounds giant sea bass make to distinguish one fish from another and also to measure the density of giants in a specific area. Clark uses a DSG-Ocean Acoustic Datalogger, which is an omnidirectional hydrophone (underwater microphone) that can record data over many days. He distinguishes giant sea bass sounds from other fish by looking at the decibel range and sound frequency they produce and comparing them with giant sea bass sounds recorded in an aquarium. This enables him to analyze mating strategies and describe spawning behavior of giant sea bass in detail. “Although there may be some echoing in the sounds produced in the aquarium it will allow me to ground truth sounds and get a general decibel range to work with,” he said.

Whatever the giants spawning behavior is, their genetic diversity is small. Allen and Andrews used mitochondrial and nuclear microsatellite techniques to determine genetic diversity. They found all the giant sea bass, those in the northern Gulf of California, as well as off Southern California and Baja, were closely related.

They’re basically one panmictic group — a panmictic population is one where all individuals are potential partners. “Our estimate is 152 breeding females, with maybe an upper limit of 500 and a range of 84 to 539,” Allen said. “So we’re dealing with a fish that’s not genetically diverse anymore; relatives are breeding with another, and we don’t know what that says to the ultimate sustainability of these populations. Sobering.”

However, the king of the kelp forest has returned. Recently a Giant Sea Bass Count was organized by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara and California State University, Northridge. Recreational divers could report any sightings around Southern California during the first week of August. Giant Sea Bass sightings numbered 23. Their results can be seen at: http://www.seasketch.org/#projecthomepage/53dbacf69743984a77bd896d/forum. Green dots indicate sightings and black X’s show where people reported that they dove but saw no Giant Sea Bass.

Next year’s giant sea bass count will probably be in early August, but check and “like” the Facebook page, The Giant Sea Bass Collective, to get updates.

Story by Mary Ann Wilson, photos as credited

Mary Ann Wilson blogs about California’s coastal and marine issues at calicoastlview.info.

Originally published in Catalina Marine Society’s OceanBights.