Southern California’s incredible giant kelp forests are home to a rich array of marine life, as well as a focus for recreational activities including SCUBA diving, snorkeling, fishing, and kayaking. But in 2003, they were invaded by an alien seaweed from Asia, and everything changed.

As a major port for trans-Pacific shipping, Los Angeles has had several non-native algae introduced here including Sargassum muticum or wireweed, which arrived in 1970; Undaria pinnatifida or wakame, that appeared in 2000; and Caulerpa taxifolia that also arrived in 2000. Thanks to a rapid and effective response, that last invasive, a plant used in home aquaria, was declared removed from the wild in 2005.

Story and photos by Dr. Bill Bushing

Novelist John Fowles once defined a weed as a “plant out of place.” A plant from Europe like broom… or an ornamental geranium in the wildlands of California is as much a weed as a native species in a home flower garden. This simple definition is easy for all to understand. Scientifically speaking, weedy species have a capacity for rapid growth and dispersal, and can out-compete more desired plants.

The most recent arrival in our waters, Sargassum horneri, was first collected from Long Beach Harbor in 2003. This alga is a native of Korea, Japan, and China as far south as Hong Kong. It has no English common name, but the Japanese call it akamoku. I refer to it as “devil weed.” At the time of its discovery, two species were recognized: Sargassum horneri and Sargassum filicinum, but scientists have now merged the two. Based on DNA studies, it probably arrived on a commercial vessel coming from the Seto Inland Sea in Japan.

In April of 2006, three small populations of it were discovered on Catalina Island at Big Fisherman Cove, Cherry Cove, and Emerald Bay near the Isthmus. It was probably introduced there by commercial or pleasure boats coming over from the mainland. Within just a few years, the exotic Sargassum had spread along the entire leeward coast of the island. It has also become established off Anacapa and San Clemente Islands, the Orange and San Diego County coasts, and down into northern Baja, California, with recent reports of it out on remote Guadalupe Island, 150 miles off the Baja coast.

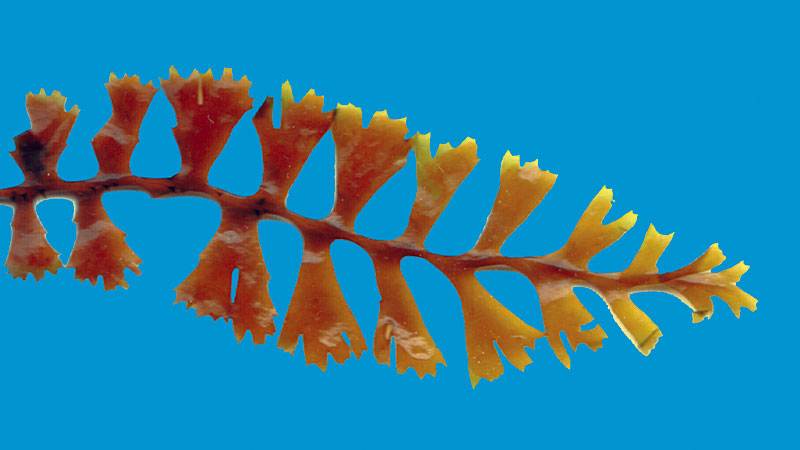

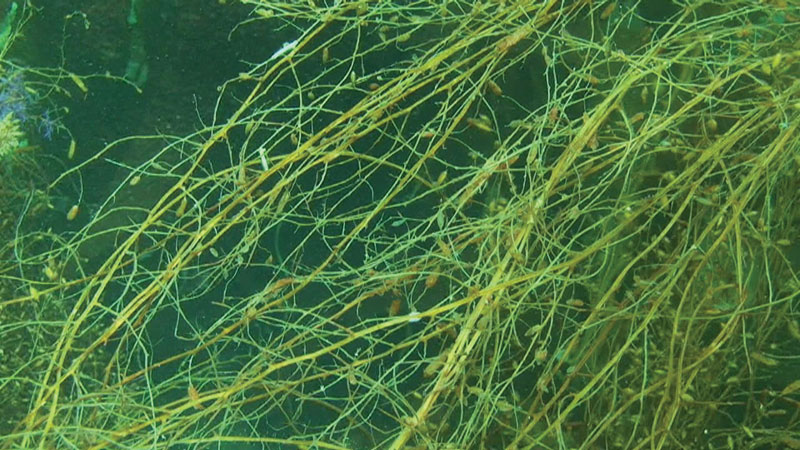

Immature specimens have flat, symmetrical, fern-like blades with notched tips. As the alga grows, it becomes loosely branched in a zigzag pattern, develops small air bladders, and may reach lengths of more than 20 feet. Very thick, nearly impenetrable forests may form.

This alga’s mode of reproduction makes it a very effective weedy invader. It matures early in its life, has both male and female components on a single plant, and is capable of self-fertilization. Young plants grow from fertilized eggs located on the receptacles of mature plants. Sargassum horneri is an annual species, completing its entire life cycle in less than a year. However, there may be overlapping generations in a single season. In Catalina waters, it appears in late summer or early fall, is well established by late fall, and dies out in the late spring. Growth of both immature plants and mature blades occurs over a wide range of light levels and water temperatures from 50 to 77 F (10 to 25 C).

As it dies, the alga becomes heavily encrusted with diatoms and invertebrates. Fragments slough off and the entire plant may break loose and drift away. Researchers have found that the amount of beached drift material from this alga at sites like Newport Beach may be second only to that of our native giant kelp. Some have expressed concern that drifting Sargassum horneri containing reproductive structures may end up colonizing new locations, and thus spread the invader. Over short distances along the mainland and island coasts, this seems quite likely. However, studies of drifting plants off Asian coasts detected little genetic exchange between isolated populations due to drifting material, and concluded it was not a successful method of colonizing new locations over distance. The discovery of the species at very remote Guadalupe Island may indicate dispersal there by boat.

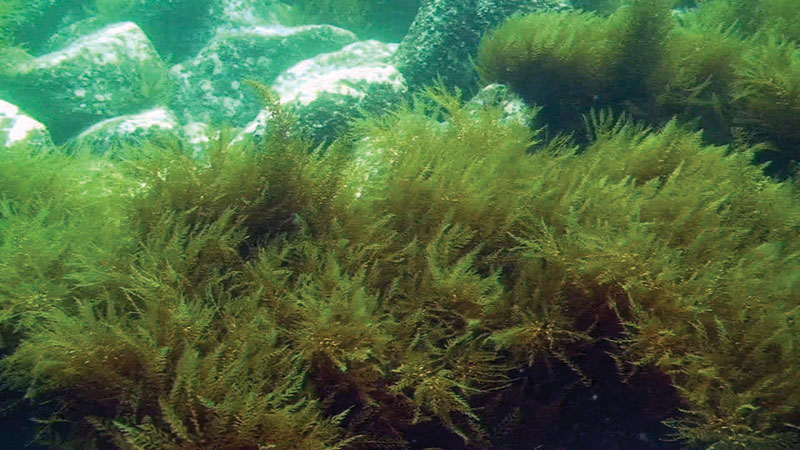

Although this alga also forms dense beds in its native regions, it is partly kept in check there by sea urchins, abalone and other invertebrates that graze on the young plants, and due to harvesting by humans for fertilizer and livestock feed. Biologist Nancy Caruso reports abalone from our waters will eat it too. On Catalina’s leeward side, it grows so thick it out-competes the native algae for substrate, light, and nutrients, forming a virtual monoculture like one might see in a wheat or corn field. Biodiversity at these sites plummets. Even our giant kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera, is affected; the Sargassum takes early advantage of available nutrients, and can quickly over-shade the young microscopic stages of the native kelp, rip off the blades of juveniles, or even tear out young plants.

One interesting observation I made was the growth of tiny, single-bladed giant kelp plants directly on the stipes of the dying Sargassum. This undoubtedly is a result of less substrate available for colonization until the invasive species completely dies out. Unfortunately, these giant kelp plants usually drift away with the dead Sargassum and do not remain at the site, further reducing the ability of the Macrocystis to re-establish during summer when higher temperatures and lower nutrient levels may inhibit it.

By crowding out the native seaweeds, it removes food sources for our local invertebrates and fish. Our native herbivores did not evolve with and adapt to this non-native alga. Most do not appear to feed on the Sargassum because it produces toxins known as polyphenols. Only after the Sargassum begins to die, and production of the toxin stops, do we see native species like garibaldi, kelp surfperch, senorita, opaleye, and others feeding in it… and then mostly on the invertebrates that encrust the Sargassum’s blades once they’ve stopped growing. I have observed giant kelpfish nesting in the thick Sargassum, but this is probably only because the native algae they normally nest in have been crowded out. I have also noticed that lobster often frequent the vertical rocky walls which are free of the invasive alga, perhaps because it is too thick on the flat bottom for them to scavenge and find food.

The winter of 2010-2011 provided an interesting insight into the balance between Sargassum horneri and our native algae. The water during the previous August and September had been much cooler than the previous five years when Sargassum became a problem. The cool temperatures enhanced nutrient levels and aided the growth and persistence of our giant kelp through summer and fall. There was very little Sargassum observed during the fall and early winter. Possible reasons may include the limited light reaching the subtidal rocky reefs due to the thick native kelp canopy, or the cooler water temperatures directly affecting the growth of Sargassum. However, in the future, as regional ocean temperatures increase due to global climate change, the advantage may shift towards the invasive species.

The negative impacts of this invader are not limited to its ecological impacts on our native species. It has economic consequences as well. SCUBA training is hampered when instructors can’t find clear areas to teach in; underwater navigation is affected by the dense growth; divers may become entangled in this stringy alga; and the release of sexual products, plant fragments, and organics decreases visibility during winter, normally our best season for diving. Some dive instructors have stopped bringing their classes to Catalina during winter because of it. Concern has also been expressed that those mainland divers who come to Casino Point may transfer reproductive components to the waters they dive on the mainland, thus spreading the alien alga there.

Catalina is also a major destination for boaters and anglers. Recently, a City of Avalon harbor patrol boat was temporarily incapacitated when fragments of this seaweed clogged the strainer in the engine’s cooling system, and it overheated. Such events may result in engine damage or other problems. Anglers may also lose fishing tackle due to entanglement in this seaweed, and game fish such as white sea bass may be affected due to the radical change in their nearshore habitats.

Scientists, such as Dr. Kathy Ann Miller of the U.C. Herbarium and Dr. Jack Engle of the Tatman Foundation, issued warnings when this alga was first discovered. A Sargassum horneri working group was formed, but apparently no action was taken in the field. The window of opportunity to eradicate this invader entirely may have already past. However, that does not mean it cannot be controlled at specific sites like the Casino Point Dive Park, which was just chosen as one of the region’s new marine protected areas (MPAs), adding urgency to the need for action. An MPA with a high density of an exotic species that out-competes the natives has far less value than one containing a naturally biodiverse native community.

Although the young plants are the best ones to target, they are much more difficult to remove. Mature plants have a single, narrow stipe raised above the tiny holdfast and can easily be clipped off. Two years ago a dive instructor cleared a portion of Catalina’s dive park of the Sargassum. As a kelp forest ecologist, I informally monitored the area, and found relatively little regrowth during that season.

Currently, even though it is not a native species, an individual diver is limited to removing only 10 pounds of wet weight per day and must have a valid fishing license to do so. We have asked the California Department of Fish and Game and its Commissioners to expedite a permit to remove this invasive non-native alga on an annual basis. Numerous local and mainland divers are willing to volunteer to do this. By allowing this to proceed, the Casino Point Dive Park could become a test site for the implementation of local control efforts, and also a location for scientific study of this invasive species. If we can control it here, and explore new ways of dealing with it, perhaps they can be extended to other MPAs and the southern California coastline in general for the benefit of all.

Story and photos by Dr. Bill Bushing