In October of 2009, I began hearing reports of encounters between local San Diego divers and Sevengill sharks [notorynchuscepedianus]. Having been diving locally since 2000, I thought this unusual, since this was the first I had heard of these encounters in nearly a decade. Between 2000 and 2006, almost no reports were documented. But in 2007, that all changed and they began appearing the dive lists, one here, two there, until it was obvious that somethingwas happening.

In October of 2009, I began hearing reports of encounters between local San Diego divers and Sevengill sharks [notorynchuscepedianus]. Having been diving locally since 2000, I thought this unusual, since this was the first I had heard of these encounters in nearly a decade. Between 2000 and 2006, almost no reports were documented. But in 2007, that all changed and they began appearing the dive lists, one here, two there, until it was obvious that somethingwas happening.

Around this time, I had my own memorable encounter with a Sevengill. I was diving off of Point La Jolla when a large 7 footer glided majestically between me and my dive buddy, who was no more than 2 meters away from me. To say we were startled would be an understatement. This incident was what first alerted me to the fact that Sevengills were making a serious appearance in the San Diego area. The reasons for this sudden appearance are stillunclear.

The most common theories to explain these unexpected visitations have been prey migration, deep ocean currents, mating/pupping, global warming, and El Nino conditions. But not enough evidence exists for a “neat theory” to develop. So as a matter of personal interest, I set up a website devoted to informally trackingSevengill shark encounters in the San Diego area [http://Sevengillsharksightings.org], not thinking much would ever come of it.

Although I put out the word for submissions on local diving boards, I was unprepared for the explosive responses I received. In the last year alone, over 20 separate Sevengill encounters were logged by local divers and 17 videoswere submitted, to say nothing of the database of high quality photographs that evolved over the months.

There was no question that somethingwas happening in San Diego in regards to Sevengills. It was now a matter of figuring out what, exactly, was happening, and why.

There aretwo factors that must be considered when attempting to determine the question: Are Sevengills making some sort of comeback, or does it just seem that way?

There aretwo factors that must be considered when attempting to determine the question: Are Sevengills making some sort of comeback, or does it just seem that way?

1. Have any baseline population studies of this species ever been done locally? If so, this would provide the numbers necessary for comparison and the development of an accurate ratio.

2. Have any studies been done to track the number of divers going into the water over the same period of time? In other words, is this a case of simply more divers entering the water, rather than more sharks being present?

Unfortunately, the answer to both questions above is: no.

No baseline studies have ever been done on local Sevengill shark populations by any of the local marine institutions. Unless the studies have been buried in the archives of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, or are only available on JSTAR, the proprietary academic database.

And no baseline studies have been done locally to survey the number of divers entering the water, or even being certified here in San Diego, in the last two years.

This means, in effect, that I am starting my own baseline study. So far, I’ve collected roughly 18 months worth of data. Probably five years of data is a good starting point.

Here is how it works:

When a San Diego diver encounters what he or she believes is a Sevengill shark [local divers are pretty savvy when it comes recognizing this species, with its distinctive thresher-like tail and pushed back dorsal fin], the diver visits the website and enters hard data about his or her encounter, such as:

– Date and time of the dive.

– Water temperature.

– GPS of the location. For popular beaches, this is readily available on Google Earth or Google Maps. If on a boat, hopefully, the GPS for the location can be obtained from the skipper or from the on-board GPS device after the dive.

– The max depth and depth during the encounter.

Then the diver enters the soft data, which is weaker as it relies on memory and perception, both of which can be altered or impaired significantly during an encounter with a large predator:

– Estimated visibility.

– Underwater activity during the encounter, such as sightseeing, photographing marine life, spearfishing, etc.

– Estimated size of the shark and its gender. Instructions are provided on the website to look for claspers between the anal and pelvic fins in order to determine whether the shark is a male. Local divers who have had repeat encounters have gotten pretty good at this and even when they have not, claspers often are clearly visible in the video they’ve taken.

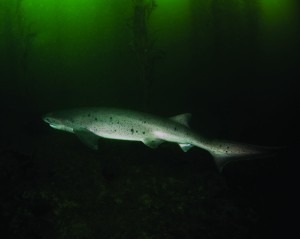

After all the relevant information has been logged, the diver is given the opportunity to submit photographs or videos taken during the encounter. In many cases, these videos and images have been surprisingly good, especially in light of the stress of the situation. Some even capture details such as the unique black freckles visible on the head and dorsal areas of Sevengills. In a recent South African study, these freckles have been used to successfully determine the identity of individual sharks.

While that is the basic data I am collecting through the website, it is only a starting point for further studies. Over the next few years I hope to collect enough photographic and video data to begin isolating the encounters by both gender and individual shark.

I am fortunate to have received sound mentoring and guidance from some very knowledgeable folks in the shark research community, namely Vallorie Hodges, DSO [Diving Safety Officer] for the Oregon Coast Aquarium and David Ebert, Program Manager of the Pacific Shark Research at Moss Landing, California. Both Vallorie and David, although extremely busy with their own research work, have been more than generous with their time and suggestions and are following the situation down here with interest. Not to be overlooked is Alison Kock, of Save Our Seas Foundation in South Africa, who works extensively with both Sevengills and Great White sharks, and who has also shared her knowledge and time selflessly.

Hopefully, with the assistance of knowledgeable divers and scientists and several more years of fruitful data collection, we may have enough information to form an educated understanding of why the notorynchuscepedianushave come to San Diego.

************************************************

Bio:

While not a shark researcher himself, Michael Bear is an experienced diver with nearly 1000 cold-water dives in California. He is currently an AAUS [American Academy of Underwater Sciences] Science-Diver-in-Trainingwith the aquarium at the California Science Center in Los Angeles.

Video by Barbara Lloyd

Sevengill photography: Scott McGee.