The dark shape materialized out of the gloom and I knew we had found the old wooden cabin cruiser. She sat upright on the sand in 135 feet of water. The small wreck was not in very good condition, but it was teeming with marine life.

We slowly made our way forward as I began to search for CF numbers on what was left of the bow. The fact that all the paint was gone did not deter me from examining the hull with painstaking detail. I searched and searched but to no avail. My dive buddy was also engaged in a thorough inspection of the same area. After nearly 10 minutes, as per our dive plan, we finally abandoned the search and began our return to the surface. With the wreck still in view, I became aware of how I had just spent my entire bottom time looking for something that not only was not going to be there, but that I didn’t care about anyway. It became obvious during our post dive discussion that neither of us could explain the reasons for the intense search. In fact, my dive buddy wasn’t even sure what he was looking for.

Words & Photos by Joseph C. Dovala

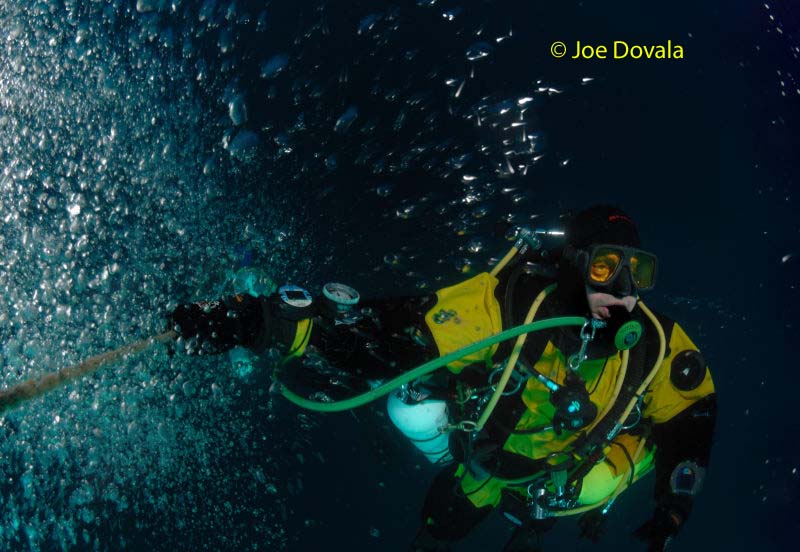

Every diver has heard of “getting narced” but many would be surprised at the peculiar and subtle ways that nitrogen under pressure can influence our behavior when we first reach our affected depth.

Effects of inert gas narcosis were first described in the early 1800’s when divers breathing compressed air exhibited “symptoms of intoxication.” Caisson workers (crews who worked under pressure for bridge and tunnel construction) were observed to break out in song at inopportune times, and Jacques Cousteau coined the phrase “rapture of the deep” during his early diving years. Appearing to be drunk is a common description of narcosis. These observations spawned the “Martini’s Law” mantra that states a depth of 100 feet is like consuming one martini, with each successive fifty feet of descent racking up another one. So, at 150 feet, it would be like drinking two stiff alcoholic beverages.

If you listen to a group of people in a hyperbaric chamber, it sounds exactly like the early stages of a cocktail party. By the time you get to around 160 feet there is a lot of giddiness, slurring of words, and hysterical laughing at jokes that are not all that funny. It is very easy to see why comparisons are made to alcoholic inebriation. While many of the symptoms are similar to intoxication, this is far too simple a generalization. Unlike alcohol, nitrogen narcosis can manifest itself within seconds and can dissipate as fast, once the partial pressure of nitrogen is reduced. Also, the synergistic effects of the diver’s health, environment, and isolation, play a large role in how the symptoms show up.

Some of the more common problems are: light-headedness, hearing sensitivity, lack of concentration, inability to read small numbers, inflexible thinking, disregard of safety procedures, amnesia, anxiety, and perceptual narrowing to name a few. There is no magic depth at which all divers will experience narcosis. The range is quite large, as some studies have showed individuals experiencing some form of narcosis in less than 80 feet, while other individuals show no effect in as much as 150 feet. The narcotic depth can even change for an individual from one day to the next. Many deep divers claim that adaptation is possible with many successive dives, going slightly deeper each time. This “adaptation” is more psychological than it is physiological, as one develops mental techniques to help overcome the narcotic dullness.

Even though the symptoms have been observed for over 150 years, it wasn’t until the 1930’s when researchers identified the inert nitrogen component in air as the culprit. Physiologically speaking, an inert gas is not used by the body for respiration or any other metabolic process. Of course, this does not make it safe, as the buildup of nitrogen in our tissues can lead to decompression sickness during a too rapid ascent. Nitrogen’s role in narcosis isn’t about bubble formation, but rather, when under pressure, can interfere with nerve impulses across the synapses of brain cells. By altering the nerve cell shape, signal transmission is slowed, thereby interfering with the thought process. This is called the Meyer-Overton hypothesis and was originated at the turn of the 20th century. Anyone who has been to the dentist where nitrous oxide is used for an anesthetic is already quite familiar with nitrogen as a narcotic substance. At surface pressure in high concentrations, it causes euphoria, drunken-like behavior, and unconsciousness. While these effects are great for getting wisdom teeth pulled, they are certainly not conducive to safe diving.

While the depth range of nitrogen narcosis differs between divers, it becomes more prevalent when diving to 100 feet and beyond. Since narcosis can be unpredictable and difficult to detect when mild, it is a good idea to be aware of some common predisposing factors. Cold, fatigue, and anxiety can bring on or exacerbate a narcotic condition. Task loading and exceeding one’s training and equipment capabilities may very well turn a mild case of impaired judgment into a serious underwater problem. Some warning signs in your dive buddy might include lack of focus or too much focus, inconsistent behavior, slow thinking, and disregard of safety procedures. It is these issues which pose a health threat rather than the nitrogen itself. Research has shown that certain drugs can have a synergistic or helping effect with nitrogen to increase the severity of narcosis. Drugs used to prevent seasickness and intestinal disorders (i.e. diarrhea) are especially prone to this because they are designed to block nerve cell signals. When using these medications, they should be tested in the 60 to 80 foot range before venturing into deeper waters, as some tests have shown significant narcotic episodes in as little as 60 feet. If you suspect that you or your partner is under the influence of narcosis it is a simple matter to ascend until the symptoms dissipate. Effects of narcosis quickly disappear with a rise of ten to twenty feet in depth.

Clearly inert gas narcosis should not be taken lightly. As with most aspects of deeper diving, it needs to be planned for and monitored. Seeking out proper training and maintaining a level of caution during the dive will go a long way toward making “rapture of the deep” manageable. Even though my dive buddy and I were “narced” in the opening anecdote, we rigidly stuck to the plan, which included a strict ten-minute bottom time. This, combined with our training, turned a potential hazard into just another dive story.

Words & Photos by Joseph C. Dovala

.