When was the last time you heard conservationists urge you to go spearfishing?

That’s what’s happening in Florida and the Caribbean as the Lionfish, an invasive species native to the Indo-Pacific region, has taken over coral reefs and other ecosystems, threatening to completely take over native fish populations. If you’re a California diver and interested in spearfishing, this may be the perfect opportunity to spear all you want, and help the environment in the process.

A Brief History of the Lionfish Invasion

Lionfish have been a popular aquarium fish for a long time, and some believe the lionfish invasion started when Hurricane Andrew smashed a saltwater fish facility in 1992, releasing six adult lionfish into the ocean. Another theory is that aquarium fish may have been released by people looking to get rid of them, similar to the way the snake population has boomed in Florida’s Everglades. It’s also possible that it’s a combination of the two, with additional lionfish being released into the wild by others in the Atlantic and Caribbean over the years.

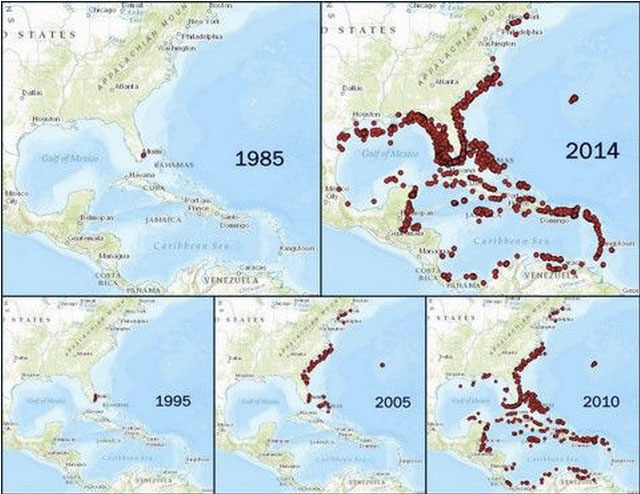

Since their introduction to the Atlantic and Caribbean waters, these prolific predators have found the perfect place to call home, and the proliferation of the lionfish over the past 2 decades represents one of the most rapid marine finfish invasions in history.

Rapid Growth

In a healthy environment, a single female lionfish produces two million eggs a year. Over the past decade, they have rapidly reproduced, becoming widely established along the southeastern U.S. and Caribbean.

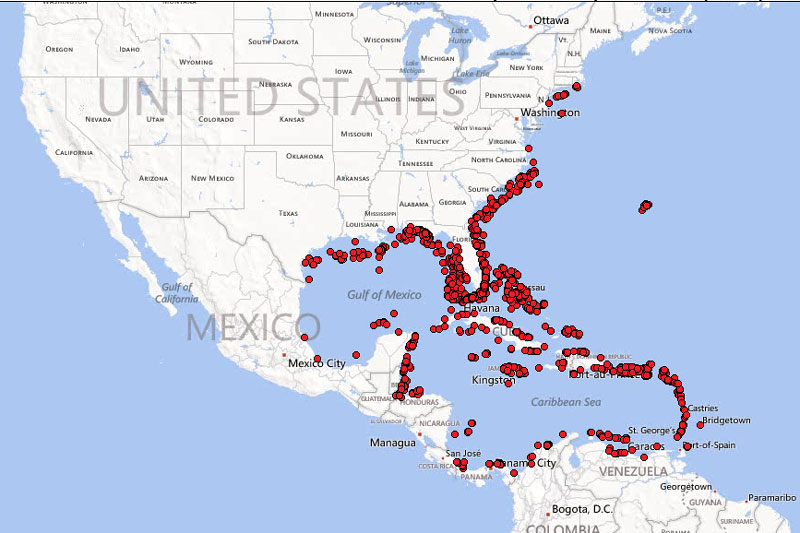

As their numbers increase, so do the areas they inhabit. Lionfish have been spreading north to New England (500 were recently collected along the south shore of Long Island), south to Panama, and scattering throughout the Caribbean. They’ve been caught off Cuba, and even as far south as the temperate regions of the east coast of South America. Their future geographic growth appears to be limited to one primary factor: they don’t particularly like cold water, and can’t survive in water lower than 50 degrees F.

Estimates of the lionfish densities have surpassed some native species, with the highest estimates reporting over 1,000 lionfish per acre. At some locations in the Bahamas, lionfish densities number 5-8 times higher than in their native Indonesian territories. In the process, they’ve rapidly taken out the diverse native fish populations formerly seen in these coral habitats, and will be “devastating” to both fisheries and recreational diving if it reaches Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, according to the Caribbean Fishery Management Council.

Unlike in Indonesia, Lionfish in the Atlantic and Caribbean regions have no natural predators to keep their population in check. In southeast Asia, sharks, groupers and other predators help control their populations. In theory, Caribbean reef sharks could eat up lionfish — after all, the sharks aren’t affected by the venomous tentacles. But most local sharks aren’t used to this relative newcomer and don’t see it as a food source; they typically stay clear. In places like Cuba and Honduras, divers have recently been spearing lionfish and physically handing them over to sharks, in the hopes that sharks will acquire a predilection for lionfish flesh. (Stay tuned – we’ll have another story on this soon!)

Fearless Predators

Lionfish are fierce predators, and unlike most fish which flee when approached by a larger animal, the lionfish will turn and faces its attacker, dip its head down, and flair out all its fins. Lionfish will attack and eat almost anything they can, feeding on both smaller fish as well as crustaceans, often corralling them into crevices with their large radial fins before inhaling them.

Not only do Lionfish like to eat just about anything, they like to eat a lot (One experiment in the Bahamas found that lionfish can gobble up 79 percent of juvenile fish in a reef in just five weeks). Their stomachs can expand over 30 times in volume, and they’ll eat anything that can fit into their mouths, consuming up to 6% of their body weight each day. Even with this appetite, when times are tough, they can survive up to 12 weeks without eating.

Lionfish Defenses

Although Lionfish put up an aggressive stance against larger animals, they also have an additional line of defense for those who get too close: venom.

Each spine of the lionfish is venomous, including 13 dorsal spines, three anal spines, and two pelvic spines. The spines are covered by a thin layer of tissue, and the spines push through as contact is made and as the spines enter their victim. The toxin contains acetylcholine and a toxin that affects neuromuscular transmission. Getting spines in the skin can be extremely painful to humans, though lionfish are not aggressive towards divers. Reactions in humans range from swelling and local pain to extreme pain and paralysis in the upper and lower extremities. The severity in humans depends on the amount of venom injected, the victim’s immune system, and the location of the sting. Their venom is rarely fatal to healthy humans, but some species have enough venom to produce extreme discomfort for a period of several days. Needless to say, proper precautions should be made by anyone handling lionfish in the wild and in the kitchen.

License to Kill

Since 2010, the Florida Keys Natural Marine Sanctuary has given out licenses to divers to kill Lionfish inside the property, and the state of Florida has set no limit on the number of Lionfish that may be taken – you don’t even need a fishing license. The REEF organization hosts a series of Lionfish Derbies with prizes awarded for spearing Lionfish, and they’ve even published a Lionfish cookbook. Cozumel, Belize, Puerto Rico, Honduras, and other locations are also encouraging divers to come spear their Lionfish in an attempt to control the populations.

Interestingly, with greater environmental awareness in recent decades, spearfishing is an activity which has been frequently frowned upon in many tropical destinations. Now those same places are actively encouraging spearfishing, hosting tournaments, and awarding prizes for the most harvested. If you’re a spearfishing enthusiast, this is a great time to head to the Caribbean, shoot as many Lionfish as you like, and help the environment.

Lionfish Tempura, courtesy of The Deep Dish Cayman

On the Menu

Once their venomous spines are removed, Lionfish are safe to eat – and tasty. They reportedly taste similar to snapper and can be found on the menu in many Caribbean restaurants, served as ceviche or in more traditional seafood dishes. Compared to snapper, grouper, dorado, and tuna, Lionfish have shown to be higher in healthy Omega-3 fatty acids, lower in saturated fats, and have lower levels of heavy metals, like mercury.

Before you harvest them, you might want to review NOAA’s safe handling guidelines.

Two years ago, officials with NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, launched a well-publicized campaign, complete with flashy pull-cards, a lionfish cookbook and a catchy slogan. As one newsletter put it, “If we can’t beat them, let’s eat them.” The effort was aimed at harnessing the power of the U.S. appetite to help battle the voracious fish that has spread far from its native Pacific waters to ravage the reef ecosystems of the U.S. Southeast and the Caribbean.

“Once stripped of its venomous spines, cleaned and filleted like any other fish, the lionfish becomes delectable seafood fare,” NOAA officials enthused.

—

In the past, consumer demand has led to the collapse of many fish populations worldwide, and currently, many species such as tuna are being heavily overfished. In this unique case, biologists, conservationists, tourist destinations, and marine sanctuaries are actively encouraging divers to help reduce the Lionfish population. It’s an unconventional approach that’s needed to help combat a species that’s thriving where it doesn’t belong.

.

References/Resources:

The Biology and Ecology of the Invasive Indo-Pacific Lionfish

Eat lionfish? Sure, but beware of the nasty toxins

Lionfish Biology Fact Sheet – National Ocean Service

Lionfish – Pterois volitans – Florida Fish and Wildlife

Story by Chris Constantine, California Diver Magazine. Photos as credited.

- halfnacker.com/Lionfish/red-lionfish-natural-predators