The following is a first-hand example of how a series of unfortunate events were made better by going back into the water for in water recompression. The article does not offer medical advice. It serves as a personal account from which people may learn.

Important: In-water recompression can be extremely dangerous and should never be attempted without proper medical supervision and in a highly controlled environment. This article is not an endorsement of this technique; it is simply sharing one person’s experience with it.

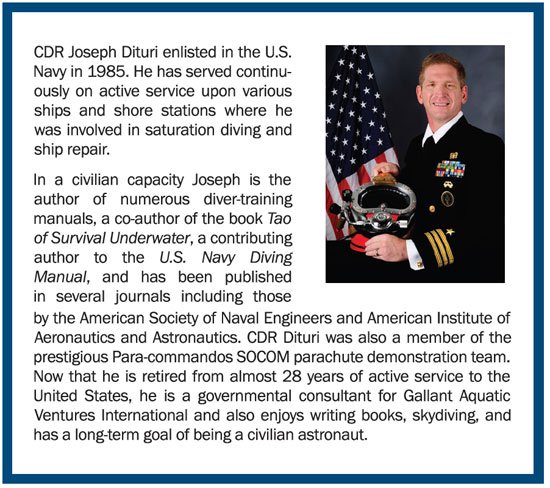

Republished with permission from author Joseph Dituri.

Immediately upon ascending the ladder onto the boat, I knew something was wrong. I felt “funny”. After removing my wetsuit, one of the support divers noticed the blotchy red patch that had started to form over my left shoulder and around the left side of my abdomen transcending around to my left lower back. It had been less than 15 minutes on the surface and I was sitting while the boat was making its way back to port. I had a flash of non-descript internal pain to my left knee. I began to rub it and wondered how long it would be until we were near the second dive site where we would afford the support divers an opportunity to dive. My entire thought process was driven toward getting myself back into the water. This thought came from adaptive unconscious (described in the later part of the article) which bares considerable importance to the ability to decide the correct course of action. About 15 minutes later, I began to feel that all too familiar pain, only this time it was in my right knee. Bilateral and progressively worsening symptoms began to cause me great concern. This was the point at which I knew I was in significant trouble.

Not wanting to be a bother to the four divers who had endured my four hour dive while they sat on the boat taking turns being in the water to support us, I concealed my pain and stomached a brief offload period at the dock which was about 45 minutes after surfacing. I could not however conceal the coughing fit that ensued with a small clearing of my throat while they were on loading some drinks from the bait and tackle shop. This uncontrollable coughing progressed and the friend driving the boat got everyone back in the boat and sped out of the channel toward deeper water than the boat basin. My rash was puffy and red and pressing on it left an indent. I had pain in both knees (a 5 on a scale of 1 to 10). I was hacking so badly I could not carry on conversation. At the speed with which the symptoms were progressing, I believe I would not have made it the 10 minute ambulance response time, followed by a 30 minute ambulance ride to the chamber or the almost assured 45 minute wait while doctors poured over me trying to find out what was wrong. I needed a cure now and hair of the dog that bit me was the only immediate remedy available.

After the 3-5 minutes it took to get the boat to 45 feet of water, I grabbed an open circuit steel 72 filled with 100% oxygen that had a green regulator on it. I put it under my arm while someone tossed the anchor. Knowing full well I may be in the water for a while, at the dock I had begun to step into a wetsuit. I could not manage to pull it any higher than up to around my hips. Face mask donned I fell forward off the boat into the water with the tank tucked under my arm unable to put fins on and with nothing else on.

I do not recall clearing my ears, the journey downward or hitting the bottom. I became aware again when Jennifer grabbed my arm and pulled me from 40-45 feet up to hang on the anchor line at 30 fsw. Jennifer had little more than a back pack on and was known for being able to dress for diving very quickly. She undoubtedly saved my life. (Thank you for that Jennifer!) By the time my dive buddy from the deep dive got dressed and re-entered the water, I had been able to pull up my wetsuit over my shoulders, was lucid and had a plan for my in water recompression cobbled on Jennifer’s slate. I had complete resolution of symptoms within minutes. I was a different person from the uncontrollable cough ladened, bi-lateral pain filled, shell of a man who thought it was a good idea to re-enter the water five minutes earlier. One of the divers brought me my rebreather and I followed out my decompression plan uneventfully watching the support divers enjoy their “fun dive” from my perch at the anchor line while slowly ascending from 30 to 20 and finally 10 fsw.

I had a fleeting thought to go to the Diving Medical Physician at Mobile Diving Salvage Unit, where I was stationed, but I was too embarrassed and did not want to face the ridicule or have to explain to the Navy what I was doing at 400 fsw on the weekend while I was on liberty. I thought I was fine until later that night when my abdomen and shoulder area that displayed the initial rash had become very painful to the touch. I was unable to sleep because when those areas touched the bed, it produced an intense amount of pain and endorphin release. After making my way to the chamber and a short ride in a “round room”, I was without pain or residual marks and live today to tell the tale.

While this story may seem improbable or impossible, it is none the less true. With this truth I intend to invite you into an alternate view of in water recompression and afford you an opportunity to discover a possible tool that could save your life if performed properly. I recognized many mistakes in this scenario. First was the most common symptom of DCI which is denial. I initially knew I had DCS, but denied the severity. The second mistake was delaying recompression. My final mistake was not being checked by a physician knowledgeable in diving medicine following my life-saving in water recompression.

If you are walking down a street and you see a truck coming toward you, do you have time to weigh all the options prior to jumping out of the way? The answer of course is no. Why would I have immediately thought that the “necessary” thing to do was get back in the water? Divers are an intelligent unique breed. The only way divers could have evolved into technical diving and rebreathers is to have a decision making process that is capable of making rapid judgments based upon little information. This notion parallels the survival skill.

As the psychologist Timothy D. Wilson writes in his book Strangers to Ourselves, the mind relegates a great deal of its high level sophisticated thinking to its unconscious. Our adaptive unconscious does an excellent job of sizing up the world, warning people of danger and setting goals and initiating action in a sophisticated and efficient manner. Wilson says that we toggle back and forth between conscious and unconscious parts of the brain. Whenever we are faced with an emergent situation, we invoke the unconscious part of our brains to assist in making the decisions. Malcolm Gladwell in his book, Blink, feels that this rapid answer is most often correct. The quality of a decision is not directly proportional to the time effort and energy to make that decision. Knowledge is power, but a delay in taking action may cause irreparable damage. Prior to making the decision to go back in the water a technical diver should take a class and prepare themselves for making the correct decision once the inevitable happens.

If we knew exactly what caused DCS, the divers at large may feel differently, but since scientists have been unable to find an exact cause, we are merely trying to treat the symptoms. DCS is so multi-faceted that some researchers have spent their whole lives trying to find the cure / cause to no end. If you ask a diver who is newly certified, “What causes DCS?”, their answer would be, “I don’t know…I think it has something to do with bubbles”. If you ask a dive master what causes DCS, you will likely get a description of a soda bottle being opened too quickly and the soda fizzing out. If you ask a Technical Diving Instructor from IANTD or a person trained in hyperbaric medicine what causes DCS, you will like get discussions of the phagocyte and leukocyte reaction to a foreign body in your blood stream coupled with the need for adequate hydration. If you ask the top five scientists who work in decompression physiology, “what causes DCS”, their answer would be, “I don’t know…I think it has something to do with bubbles”.

This is just one case where the contentious topic of in water recompression was the best over-the-counter remedy. This could have gone very wrong and I may not have survived the descent. Authors like Richard Pyle, Don Shirley and Tom Mount have scribed their accounts of the utility of this “trade secret”. There are two major points to take away from this article: 1. In water recompression is the best source for immediacy of care when a diver has a DCS. 2. In water recompression is not the only thing a diver needs to do if they have a DCS. In water recompression is by no means a medical treatment. It is merely a method of lessening the severity of issues that a diver will encounter because of DCS and affording immediacy of care.

Best Publishing Company is the world’s foremost publisher of books on diving and hyperbaric medicine. For more information and resources, please visit the Best Publishing Company website www.BestPub.com. You can reach them at info@bestpub.com or (561) 776-6066.

Best Publishing Company is the world’s foremost publisher of books on diving and hyperbaric medicine. For more information and resources, please visit the Best Publishing Company website www.BestPub.com. You can reach them at info@bestpub.com or (561) 776-6066.