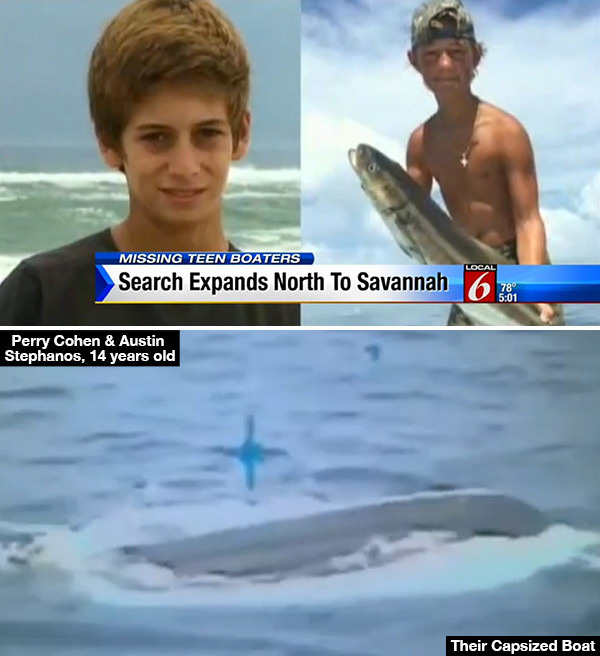

On Friday, July 24, two young teenagers on the east coast of Florida went out for an afternoon of fishing in their 19 foot boat. Having grown up on the water, their parents allowed to fish on their own inland and close to shore, but they apparently stretched their boundaries, headed offshore, and got into trouble on the water when a sudden storm kicked up and capsized their boat, which was later recovered 67 miles away. Sadly, two weeks later, no sign of the boys has been found and the Coast Guard called off the search after 7 days. The family is continuing the search along the entire east coast with the help of private pilots, boaters, and local rescue organizations.

There is much thought and speculation as to what may have happened, and of course many questioning the seaworthiness of their boat, the qualifications of two 14-year olds to be out there by themselves, and the decisions of their parents to let them go out to sea. As in many tragedies, it’s easy to point the finger and assign blame after the fact, but it doesn’t help the victims or their families. My thoughts and prayers go out to them.

What actually happened on that Friday afternoon may never be known, but some insight tells us that the young fishermen were, in at least some way, unprepared for what they encountered. While finger-pointing and assigning blame can be damaging and unproductive, learning from a tragedy such as this can help us be safer in the water, and potentially save lives.

Without breaking down and investigating all dive accidents, their causes, and prevention, let’s focus for a minute on something that could happen to scuba divers, similar to the incident in Florida with fishermen: being caught in an unexpected storm, current, or other event that separates divers from their point of entry on shore, or separates them from their boat. As coastal divers, it’s something that should be taken into consideration on every dive here, and equally so when traveling to other destinations.

Gearing Up

Dive training, experience, and judgment are obviously all extremely important, as is understanding the specifics to your location, including weather patterns, currents, and local procedures. When diving in open water, there are also a few pieces of gear that should be considered essential for offshore diving.

From the perspective of a boat operator, a scuba diver, swimmer, or snorkeler is extremely difficult to spot at the surface at even relatively close distances – the fact is that the ocean is very, very large, and you’re very small. With only the head and top of the shoulders visible there’s not much to be seen, and add in some wind, surface chop, or fog (and of course, night) and you’re nearly invisible to boats and airplanes. It’s because of this that you need something to increase your visibility at the surface.

Your first piece of essential equipment is a Surface Marker Buoy (SMB). A surface marker buoy is sometimes deployed at depth to indicate the diver’s position to their surface while underwater, and at the surface can be inflated and extended into the air, enabling a diver to be spotted from a distance. At night, a flashlight can be put inside to illuminate it as well (read our article “Have You Hugged Your Safety Sausage Lately?” here for more information). Some boats do require them, some boats will loan you one, and many other boats don’t check to see if their divers are carrying one. I’ve been on many dive boats where people don’t have even a simple tube with them.

Simply put, every diver needs one. You can find them in your local dive store or online, and prices range from $20 for a basic tube to around $100 for a heavy duty tube with radar-reflective tape and an over-pressure relief valve. Smaller tubes can be simply folded or rolled up and stored in a BC pocket. If you don’t dive with one, buy one now and carry it with you on every dive. Your local dive shop will have one for you.

The second piece of essential gear is an audible signaling device. Just like it’s difficult to be seen bobbing in the water, your voice can be easily drowned out in even a short distance on the water, especially with wind, surface chop, and weather. For about $5, you can buy a simple plastic whistle that attaches to your BCD that you can use to get attention at the surface. It’s cheap, weighs nothing, and extremely valuable when trying to communicate at the surface.

If you want to take it to the next level, for about $80, you can purchase a Dive Alert whistle, which is air-powered and many times as powerful. DiveAlert uses a small amount of air from your SCUBA tank to make a piercing, loud sound in air or water. People have been able to hear a DiveAlert one mile away above water. In conditions where visibility is limited, a DiveAlert can be a life saver.

Whichever you choose, you need some audible signaling device with you on every dive.

It’s also strongly recommended that you take a powerful light with you on every dive – day and night. Modern LED lights have improved tremendously, offering bright light and long burn times. If you’re ever adrift at nightfall, even a small LED light will make a tremendous difference in the ability for rescuers to spot you. You can buy a bright, rechargeable LED light that weighs almost nothing and with clips onto you or you can carry in your pocket. LED flashlights for diving range from $50 to over $1,000. For safety use, a basic rechargeable LED light is adequate.

A signaling mirror is another good option, and during the daytime will be able to communicate over a far greater distance (thanks to Wayne Phillips for pointing this out!). Scuba.com has one for $12.95 – another low-cost safety item that you should consider for your kit.

So far, for a surface marker buoy, basic whistle, and LED light, you’ve spent under $150 (maybe less), and you’re probably better equipped than many divers on the boat. But these are not luxuries or for advanced divers only – they should be considered mandatory for all divers and carried on every dive.

Have a few hundred dollars more? If so, you can buy one device that can greatly expand your ability to be located in the water.

Like many divers, I’m a big fan of the Nautilus Lifeline GPS Radio. The Nautilus Lifeline is a compact, submersible handheld VHF radio with with GPS capabilities. Waterproof up to 425 feet deep, the Lifeline is carried along with the diver during the dive, in a pocket or clipped to the BCD with a D-ring. It’s a solution that is about as compact as an SMB, yet allows a diver to communicate with any boats in roughly a 6-mile range. (The Nautilus Lifeline has a stated range for its digital distress signal of up to 34 miles). You can buy a Nautilus Lifeline for around $299.

Now imagine that the worst case scenario has just happened to you. You’re diving offshore and when you surface your boat is gone, or you were shore diving, got caught in a current, and pulled out to sea. It’s in the evening, the sun is going down, and you’re alone. Would your $180 investment in a good whistle, flashlight, and surface marker buoy have been worth it? For another $300, you can have a radio where you can speak directly to area boaters, or send out a distress signal to everyone up to 34 miles away.

We can’t predict or prevent all accidents from happening, but by follow the Boy Scout’s “Be Prepared” rule, we can be better equipped to handle emergencies when they happen. Be committed to being as prepared as you possibly can be and always dive with the necessary safety gear.

It could save your life.

– Chris Constantine

Please discuss! All input, thoughts, ideas, and suggestions are welcome. By sharing your insights and experiences we can all become safer divers.