After a successful week of business meetings in Salt Lake City, it was time to focus on something fun. What to do in the shadow of the Wasatch Mountains? Scuba diving, of course!

Within driving distance of the city are two interesting dive spots. For divers looking for a unique adventure, or for those in Utah simply looking to get wet, these spots provide an easy fix.

Before donning the dive gear, however, we headed west on I-80 towards the Bonneville Salt Flats. Any visitor to this area should take the time to see this marvel of nature. Stretching over 30,000 acres, this thick crust of salty soil is so perfectly flat that visitors imagine they can see the curvature of the Earth. It is barren, completely devoid of life, and is home to the famous Bonneville Speedway, where racers have set and broken land speed records for decades.

The Bonneville Salt Flats stretch as far as the eye can see

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza & Christopher P. Weaver

The Salt Flats were formed when an ancient lake dried up. The lake, now referred to as Lake Bonneville, was huge, filling much of the Great Basin in Utah. About 15,000 years ago, Lake Bonneville was the size of Lake Michigan and covered one-third of Utah and parts of neighboring states.

As time went on, the lake began to recede and eventually shrank below its outlet and as a result the water became salty. As the water continued to evaporate, salt deposits were left in many areas. The Great Salt Lake is a remnant of Lake Bonneville. Today, all that remains are the salt flats, which look like an expanse of snow and ice until you get close and realize that snow angels are not really possible!

Should the sign say “Diving Elevated”?

On the way back to the city, we took the exit towards Grantsville and arrived at the Bonneville Sea Base.

The Bonneville Sea Base is home to a natural spring that rises up through the ancient remnants of Lake Bonneville and reaches the surface as salt water. In fact, the salinity of the spring is equal to that of sea water, which enables the existence of ocean fish in this inland location.

But how do the ocean fish get here? Well, in an inspired move, the owners of the Bonneville Sea Base work with nearby universities and research facilities to take their fish after they have been studied and relocate them to the sea base. Otherwise, these fish would be euthanized. Over the years, the fish have reproduced and local populations are now resident. Divers can find butterfly fish, mullet, black drum, jacks, snappers, grunts, schools of pinfish, tunicates and much more.

The entrance to the dive site at Bonneville Sea Base

The Bonneville Sea Base consists of four separate dive sites: White Rocks Bay, Habitat Bay, The Trench and the Abyss.

We dove the Abyss first, as it is the deepest part of the facility. Reaching depths of 62 feet, divers must realize that the entire location is at an altitude of 4293 feet. This means that the maximum depth is altitude adjusted to 84 feet. Dive profiles must be calculated accordingly.

The Abyss is really just a circular, barrel shaped hole in the ground and it is best used for divers looking to practice skills.

After a surface interval and a snack, we explored the Habitat Bay and White Rocks Bay area. Here, we did see some of the resident fish and even came across a small sunken boat in about 20 feet of water. The visibility was not great, but the water temperatures were in the warm mid-70s and the experience of diving an inland spring filled with tropical fish was quite unique.

The Bonneville Sea Base dive site entry point

The Bonneville Sea Base is about 40 miles west of Salt Lake City and is worth a try.

Our next adventure took us to the small town of Midway, located about 28 miles southeast of Salt Lake City and situated on the opposite side of the Wasatch Mountains. We came here to dive the Homestead Crater.

As melting snow found its way deep into the earth on this spot about 10,000 years ago, it percolated upward after being heated by forces in the Earth’s interior. Rising to the surface, the warm water gathered minerals and the result was a limestone mound that is now known as the Homestead Crater. It continues to be a geothermal hot spring to this day, with water temperatures holding steady at 90-96 degrees at all times.

No wetsuit needed in the Homestead Crater!

At the Homestead Crater, the limestone dome is open at the top, dozens of feet above the water level, permitting cooler air to enter the chamber. Divers enter through a small walkway that has been cut into the side of the dome and can easily gear up on a floating platform that has been installed in the crater.

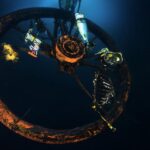

With water temperatures as high as they are, a wetsuit is not needed. In fact, the water is almost uncomfortably warm after a while! We descended along the rocky walls of the chamber to the bottom, reaching a depth of about 65 feet. There isn’t much to see, but the experience is certainly a one of a kind. The staff have installed a few playful structures and surprises at the bottom to entertain divers, but for us the most interesting part was locating the source of the hot water. Directly on the bottom, we found a roiling mud pot which was spewing extremely hot water into the chamber.

The Homestead Crater is at an elevation of 6000 feet so this, too, is an altitude dive. Divers must calculate the dives properly and adhere to safe altitude diving practices. One critical consideration is the ascent rate. Divers accustomed to rising at about 60 feet per minute should cut that in half. Because of the change in pressure due to the altitude, there is a greater risk of decompression sickness and a slower ascent rate is crucial.

A wagon wheel, adorned with figurines, at 40 feet in the Homestead Crater

Both the Bonneville Sea Base and the Homestead Crater offer divers a great way to dive the interior of Utah. The welcome signs along the highways as you cross into the state use the motto “Utah: Life Elevated” but perhaps they should say “Utah: Dive Elevated”!

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza & Christopher P. Weaver

- : Training platform in the Abyss at Bonneville Sea Base.

- The Bonneville Sea Base features the Abyss.

- The Bonneville Sea Base s home to “rescue” fish

- The bow of a small sunken boat in the Bonneville Sea Base

- The rocky walls of the Homestead Crater

- The source of the geothermal hot water at the bottom of the Homestead Crater

- A wagon wheel, adorned with figurines, at 40 feet in the Homestead Crater

- Should the sign say “Diving Elevated”?

- The Bonneville Salt Flats stretch as far as the eye can see

- Snow angels are not possible in the hard salt

- The entrance to the dive site at Bonneville Sea Base

- On cold days the shelter at the Habitat Bay is a welcome feature

- The Bonneville Sea Base dive site entry point

- The Bonneville Sea base is a natural salt water spring

- The dive site known as the Abyss at the Bonneville Sea Base

- Parking for divers only!

- A rocky dome hides the unique Homestead Crater dive site below ground

- Queueing up to enter the crater

- A panoramic view of the Homestead Crater Dive Site

- Rental gear awaiting use at the Homestead Crater

- No wetsuit needed in the Homestead Crater!