In the summer of 2009, using advanced computer software processing, Dean Morrow discovered a large shape deep below the waters of San Clemente Island. Based on what he saw in the data, there was little doubt that he had found a very large shipwreck far below the surface. The question now was what wreck was it, and how had it got there. Since San Clemente has long been used by the US Navy for target practice, and weapons development/testing, the chances were good that the target had been sunk deliberately, but the only way to know for sure was to dive it and find out.

There was only one problem – Dean wasn’t a diver. His interest in shipwrecks came mainly from his passion as a fisherman. Generously, Dean shared his information with some local divers who were able to operate at the target depth – over 250 feet below the surface.

——————————————————————————-

Words by Nick Ambrose, Photos by Dan Bramley

——————————————————————————-

Late in 2009, two groups of divers visited the wreck and confirmed it was a Fletcher Class (World War II era) US Navy Destroyer. However, no definitive identifying markings were located (the most likely place on the stern was covered in a large layer of marine growth and a number of large sponges).

At this point Gary Fabian (of http://www.ub88.org), armed with video taken by divers, embarked on a significant amount of historical research in order to try to narrow down the identity of the wreck. The main identifying characteristics that Gary used were: Three 5-inch guns in the aft section, the ships square bridge, the single pole main mast and two torpedo tube foundations. It was also noted that the ship was missing its number 2 and number 5 5-inch gun turrets and the forward set of torpedo tubes.

Gary initially checked with the California State Lands Commission, who suggested the wreck may be the USS Burns (DD-588), sunk in 1976, but more verification would be needed to increase his confidence in the identification. Gary then began researching the history of USS Burns, helped by Jim Carver (former crew member USS HULL) who recalled sinking a target off of San Clemente in 1976. Various conflicting sink dates for the targets confused the search for a while, but finally, CDR Paul J. Piper (USNR-Ret) who was the gunnery officer aboard USS HULL, who personally fired the guns that sunk the target was able to confirm the location, orientation and condition of the wreck. The wreck was sunk during testing of the MK71 8” Major Caliber Lightweight Gun (MCLWG).

After an exhaustive process of elimination, Gary eliminated all Fletcher Class Destroyers with rounded bridges that had been scrapped, sold, transferred, sunk or still afloat. This initial process reduced the target list from 175 ships down to 17. Gary then reduced this number further, using the specific details from the video of the wreck (shot by John Walker). This reduced the list further to just two possibilities – the USS Bell (DD-587) and USS Burns (DD-588). Based on the USS Bell’s reported sink data of May 11, 1975, Gary eliminated this from the list, leaving just the USS Burns. If the historical record on the USS Bell is inaccurate, there is still a small possibility that this wreck may be the Bell, but until definitive evidence from the wreck itself is retrieved, the working assumption is that this is in fact the wreck of the USS Burns (DD-588).

After an exhaustive process of elimination, Gary eliminated all Fletcher Class Destroyers with rounded bridges that had been scrapped, sold, transferred, sunk or still afloat. This initial process reduced the target list from 175 ships down to 17. Gary then reduced this number further, using the specific details from the video of the wreck (shot by John Walker). This reduced the list further to just two possibilities – the USS Bell (DD-587) and USS Burns (DD-588). Based on the USS Bell’s reported sink data of May 11, 1975, Gary eliminated this from the list, leaving just the USS Burns. If the historical record on the USS Bell is inaccurate, there is still a small possibility that this wreck may be the Bell, but until definitive evidence from the wreck itself is retrieved, the working assumption is that this is in fact the wreck of the USS Burns (DD-588).

The USS Burns is a Fletcher class destroyer over 376 feet long, more than 39 feet across, displaced in excess of 2000 tons, and had a top speed of over 35 knots. She has an extensive war record, with a long and distinguished history in the Pacific (earning her men the right to wear 10 battle stars on their Asia-Pacific service ribbon, in addition to many other awards). She logged over 250,000 miles in the region.

Named after Captain Otway Burns, she was launched August 8, 1942. After her commissioning at Charleston, North Carolina on April 3, 1943 and a six-week shakedown, she steamed via the Panama Canal directly into action against the enemy, performing at least 20 operations with the Task Force 38/58.

Her first chance for some serious action came around midnight Jan 30,1944 when she encountered a 4-ship enemy convoy. She gave chase, eventually sinking 1 medium oiler, 1 medium cargo ship, and 2 smaller ships in the 34 minutes during which she maintained fire, and rejoined her group the following day while flying a broom from her masthead (to indicate a clean sweep of the enemy). Shortly after, she added to her kill list a 180-foot Japanese sub-chaser.

Her first chance for some serious action came around midnight Jan 30,1944 when she encountered a 4-ship enemy convoy. She gave chase, eventually sinking 1 medium oiler, 1 medium cargo ship, and 2 smaller ships in the 34 minutes during which she maintained fire, and rejoined her group the following day while flying a broom from her masthead (to indicate a clean sweep of the enemy). Shortly after, she added to her kill list a 180-foot Japanese sub-chaser.

It wasn’t just in battle that the Burns distinguished herself, she also performed admirably at escort duties and as a rescue ship before being re-assigned to Seventh fleet, where she participated in the bombardment and occupation of Borneo at Brunei Bay and Balikpapen.

With the main support requirements diminished, the Burns settled down to routine duties with the North China fleet before returning to the US, where she operated briefly on the West coast until finally being decommissioned at San Diego on June 25, 1946.

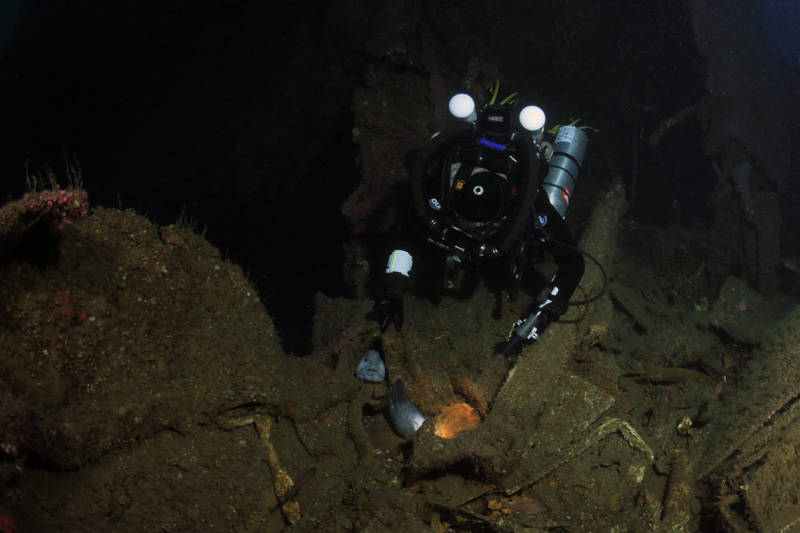

I was fortunate enough (Along with Andy Huber and Roger Bly) to be able to join Deep Outdoors on a 2-day trip to dive the USS Burns in April of 2010 (and a subsequent 2 day trip in July). The Burns sits in deep water, between 220 and 270 feet, and requires very careful planning and execution to dive her safely. Due to the amount of decompression bottles we had to carry and the size of the wreck, we also elected to bring scooters both to reduce our workload moving around the wreck, and to allow us to cover the entire site.

Arriving at the dive site, we had excellent surface conditions, almost no swell or wind, and cool but sunny weather. The shot line was quickly deployed to the wreck and the dive masters assigned every team of divers a place in line, with teams staggered by approximately 20 minutes to avoid a big traffic jam at the longer 20-foot stops. Most of the divers on this trip were diving on Closed Circuit rebreathers, but Andy, Roger and myself were diving Open Circuit.

Splashing into the water, we performed our surface checks, and after a quick fix to a leaking Argon bottle, we began the long descent to the wreck. A feeling of nervous anticipation came over me as I deployed the video lights and powered up the camera. We would be, relatively speaking, some of the first people to dive on this site.

Visibility was excellent on our descent as we moved through the clear blue water. A vague shape came into view from around 150 feet. The first real sighting of the size of this wreck took my breath away. We had arrived on the hull side, close to the propellers. Scootering down the underside of this wreck and seeing the props gradually come into focus was simply amazing. However, as big and impressive as the propellers are, it’s still hard to imagine something of this size propelling the Burns along the surface at over 30 knots with a heaving wake of water following along behind. Just imagining the forces needed to accelerate, stop and turn this boat is unimaginable.

The whole wreck is simply covered in life of all colors, but the props and stern section were also covered in large white sponges (making it quite difficult to expose the area of the wreck where the name could still be attached).

Passing by the propellers, I caught a brief sight of a Flag rockfish, which always remind me of clownfish. This was quite a rare sight for me, and a fish that I so far haven’t seen any shallower than 190 feet. We passed by what looked like a big winch on the stern, also covered in life, then one of the rear guns came into view, looming ever closer out of the darkness. We paused at the gun a while, my two buddies performing loops and barrel rolls on their scooters while I collected video footage, trying to imagine the sheer sound and forces generated when this enormous gun was used to spit oversized bullets toward the Burns’s enemies.

Continuing on down the wreck, we passed the stacks that had collapsed onto the bottom, marveling at their huge size. The sheer amount of damage done to this wreck as it was used for target practice, and finally as it careered into the bottom is staggering, thick sheets of metal have been crushed and folded like thin sheets of paper. What incredible forces must have wrought this level of destruction.

Next we traveled past the torpedo tubes, pausing to video them before scootering past a large assortment of piping and machinery before meeting the bow which lies crumpled on its side in the sand. I spent a few minutes filming my buddies scootering around the bow area, performing loops around the forward guns.

We then moved a little more aft where we encountered two large wolf eels which my buddies were kind enough to illuminate for me. We then scootered all the way along the deck railings, splitting the huge schools of fish as we did. Finally, our 25 minutes of bottom time was up, and we made our way back to the upline to start our lengthy decompression.

With the top of the wreck at 220 feet and the bottom 270, we decided the dive was an average of 250 feet for 25 minutes. With the 3 deco gases we had brought (35/25, Nitrox 50 and 100% O2), this gave us 75 minutes of total decompression from 120 feet to the surface, with our deeper stops (used to prevent the formation and expansion of small bubbles) starting at 190 feet, followed by stops every 10 feet for 1 minute. This gave us a total dive time of around 2 hours.

I have a total of 4 dives on this wreck so far, and consider it the best wreck site I have had the fortune to dive in California. Each time I find something different to marvel at, and I have had uniformly good visibility on every occasion so far.

Obviously this site is not for every diver, but I strongly encourage all those that are able and qualified for this to get out and dive this incredible wreck.

——————————————————————————-

Words by Nick Ambrose, Photos by Dan Bramley

——————————————————————————-

Footnote: A huge thanks to Gary Fabian for allowing me access to his extensive research, as well as Dan Bramley for supplying the still photographs.

(YouTube video by pinchibuso)