On a clear, sunny day on Aug. 24, 1943, U.S. Navy pilots William Parks and Richard Moore were flying their SBD Dauntless dive bomber on a training exercise off the coast of Pacific Beach, San Diego. Their mission: tow a target behind them for the purpose of naval gunnery practice. The mission was unsuccessful and the plane a total loss, along with the crew who perished in the crash. The plane settled on the bottom of the sea in nearly 200 feet of water, where she’s rested quietly for the last 76 years.

An A24 Banshee (the Army’s version of the SBD) releasing a bomb. Note the dive brakes just behind the wing. Public domain photo.

The Douglas SBD Dauntless is a World War II American naval scout plane and dive bomber that was manufactured by Douglas Aircraft from 1940 through 1944. The SBD (“Scout Bomber Douglas”) was the United States Navy’s main carrier-based scout/dive bomber from mid-1940 through mid-1944. The SBD was also flown by the United States Marine Corps, both from land air bases and aircraft carriers. The SBD is best remembered as the bomber that delivered the fatal blows to the Japanese carriers at the Battle of Midway in June 1942. The type earned its nickname ‘Slow But Deadly’, from its SBD initials, during this period. (1)

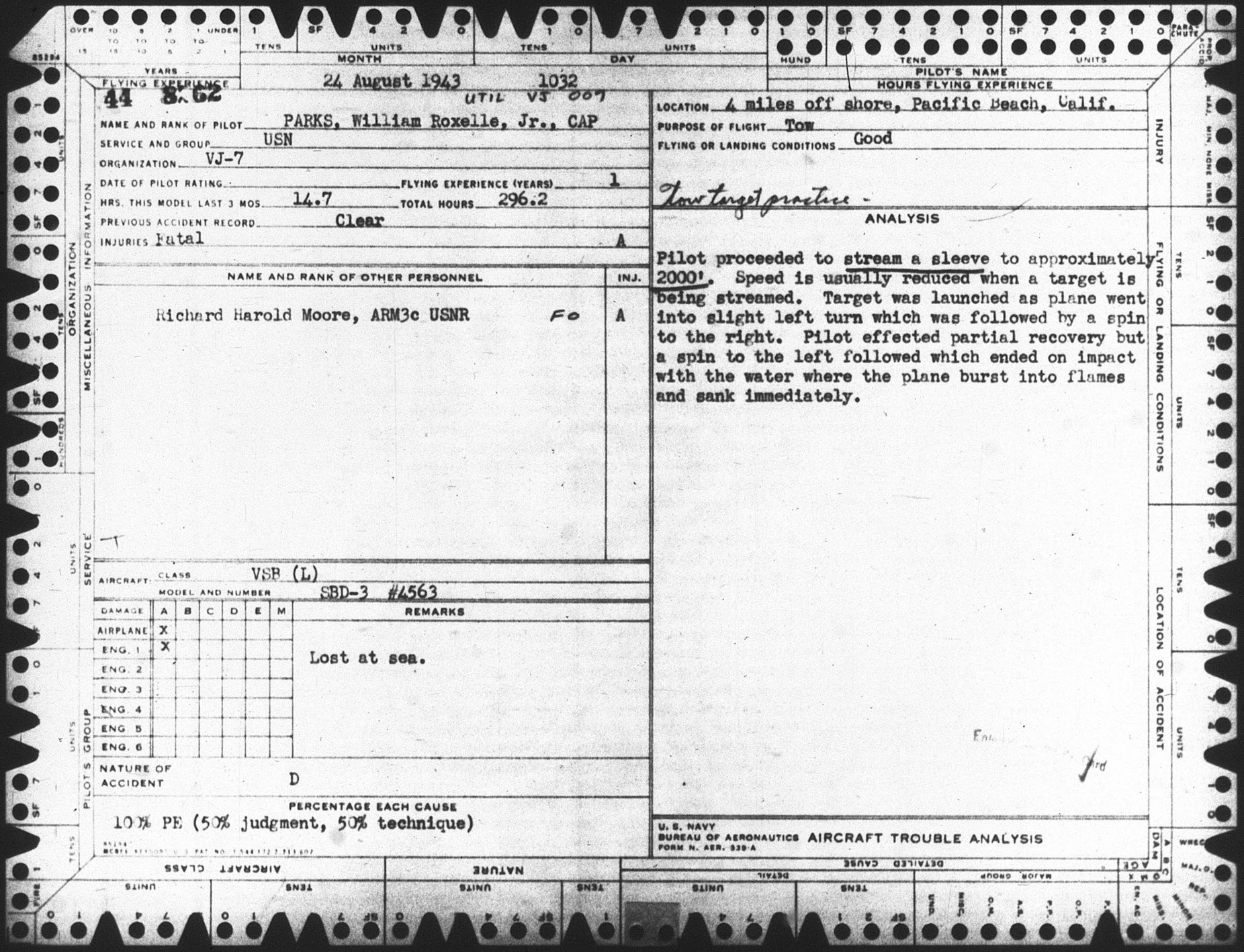

After the incident, the Navy did a full investigation. According the official Navy Accident Report (shown above):

“The pilot proceeded to stream a sleeve to approximately 2000’. Speed is usually reduced when a target is being streamed. Target was launched as the plane went into a slight left turn, which was followed by a spin to the right. Pilot effected a partial recovery, but a spin to the left followed, which ended on impact with the water, where the plane burst into flames and sank immediately.” The reported also noted that the cause of the accident was “50% judgement, 50% technique”.

Tyler Stalter is a San Diego technical diver who enjoys looking for sunken wrecks and planes off the coast of California. Being specially trained in mixed gas use, he can explore depths beyond the normal range of scuba divers. He has dived such legendary wrecks as the USS Monitor and the Andria Doria, off the coast of New York, which is considered to be the ‘Mt. Everest of technical diving.’ He had heard stories of undiscovered wrecks from his late mentor, tech diver Steve Donathan, and had made a point of paying attention to unusual patterns in bathymetry data during his research of potential dive sites.

A few years ago, while out boat diving with some friends, Tyler saw what he thought might be a barge on the bathymetry scope at around 200’, but didn’t pay much attention to it because barges are generally not that interesting to most tech divers. More recently, however, he decided the area might be worth a second visit, so on Oct. 23, of 2019, he went out again with Lora Meyers of Marissa Dive Charters in San Diego and his dive buddy Dan Jackson—and, this time, they came prepared: they brought mixed gas tanks (trimix) for longer bottom times and a camera to document whatever might be on the bottom. Dan had done one ‘bounce dive’ on the object previously, but due to poor underwater conditions, they were unable to determine what it was.

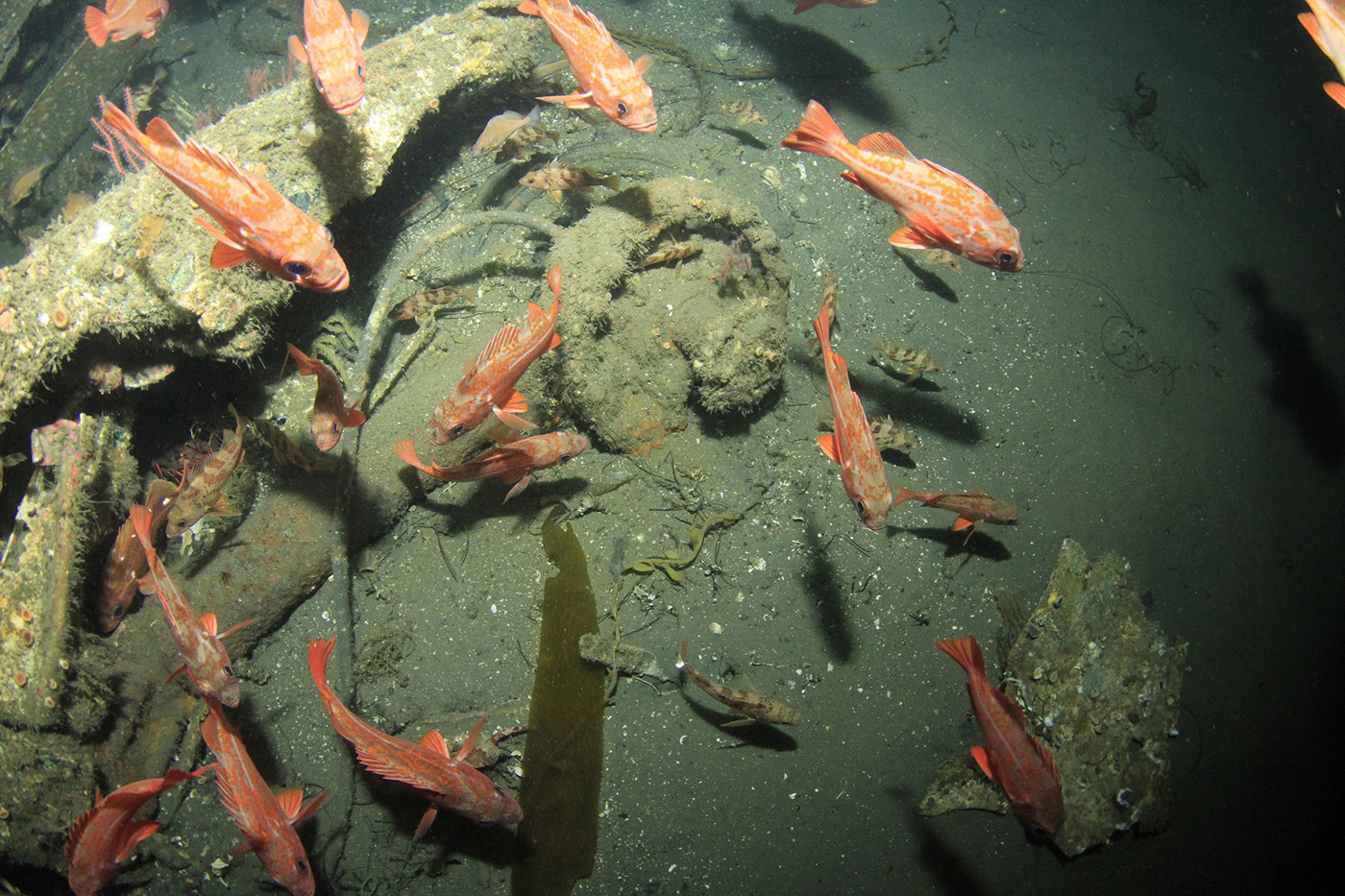

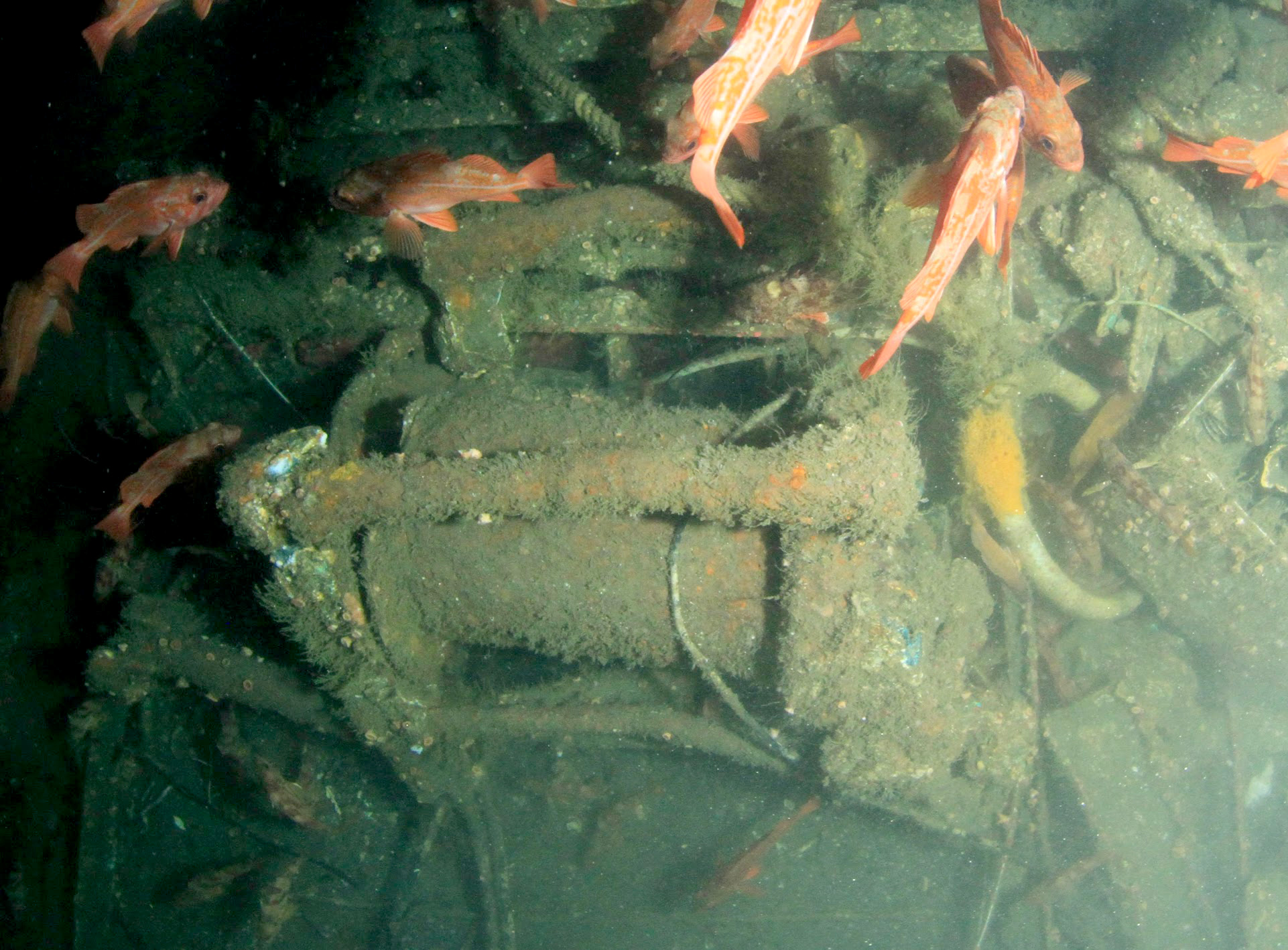

This time, they both went down to 197’ and the first thing Tyler saw was an intact tire and thought, ‘That’s weird, there’s a spare tire on this shipwreck,’. Then he looked up and saw the engine, a 9 cylinder radial engine with 2 propeller blades sitting in the sand in front of it and he knew that this was an aircraft. He and his dive buddy made sure to document prominent features of the aircraft and using these photos of the wreck site, and using this information they were able to identify the plane.

First was the engine – a 9-cylinder radial. Second, the extended dive brakes on the trailing edges. Finally, a mysterious winch was mounted to the belly of the aircraft.

Side view of the 9 cylinder engine. Note one of the cylinder heads is missing, exposing the piston. Photo: Dan Jackson

Extended dive brakes on the trailing edge of the wing was key in identifying this wreck. Photo: Dan Jackson

Tyler contacted Steve Lawson, an avid wreck diver with California Wreck Divers, who was able to help identify the engine. Using this information, he looked up what type of aircraft was equipped with this model engine, as well as these extended dive brakes. Only one aircraft, an SBD Dauntless Dive Bomber, had these extended dive brakes.

Lastly, he researched why there would be a winch mounted to an aircraft and learned about “target tug” aircraft. These aircraft were retrofitted to tow targets for Naval anti-aircraft target practice. Lawson also tipped him off to an online repository of war diaries that documented aircraft losses off the coast of Southern California during World War II. Tyler came across a war diary entry of an SBD Dauntless that had crashed while towing a target approximately 3 miles off Pacific Beach on August 24, 1943, the exact location of this aircraft.

To be doubly sure, Tyler contacted the Navy History and Heritage Command (the government agency that oversees all US Navy wrecks) regarding the wreck because he knew that the plane fell under the Sunken Military Craft Act, which prohibits disturbing the site without a permit. The Sunken Military Craft Act does not affect non-intrusive recreational diving, which means you can look, but may not disturb a wreck—especially one which may possibly be a war grave. (2)

Without being able to see the manufacturer’s plaque with the serial number, one can never be 100% sure, but the facts all seem to point to the aircraft mentioned in the Naval Accident Report cited above.

Tyler and Dan will keep diving and researching the plane to get more information on it, but in the meantime, they have the satisfaction of knowing that they have helped the US Navy document a missing plane from World War II.

References:

1. Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_SBD_Dauntless?fbclid=IwAR2ssgeK3xdAR9g_TaXqZjOZGJca0l6xbN9wHc0omxPnxzD0TICXoaCTRnc

2. US Navy Archives: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/underwater-archaeology/policy-and-resource-management/faq.html#diving

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Special thanks to Michael Bear for writing this story for CaliforniaDiver.com

Michael Bear is the Citizen Science Director at Ocean Sanctuaries.

Visit their website here and Facebook page here.

Photos by Dan Jackson, unless otherwise noted.