Dr. Glen Egstrom’s research in diving performance and development of fitness principles are timeless. His diligent work, role model and influence, continues to inspire and permeate the sport, business and safety of diving. While developments in diving and equipment were taking place around the globe, right here in the heart of America and later the heart of Los Angeles, a diving legend was working behind the scenes, often with little recognition, protecting his country, future divers and the diving industry.

“The first thing that became obvious to me, and a part of my research, was answering the question “fitness for what?”

– Glen Egstrom, Ph.D.

When was your first SCUBA dive?

My first dive was in a fresh water lake in North Dakota in 1946 with a rebreather. A friend brought it back from being in the Navy where it was used for going into contaminated compartments. It consisted of an oxygen cylinder, CO2 absorbent canister and a breathing bag and all I knew was to put your mouth on the mouthpiece and breath. It leaked and I got a dose of caustic soda. It taught me a lesson.

I didn’t dive again until after moving to Los Angeles where my uncle (actor Dewey Martin) gave me a set his set of doubles, a two hose Aqua Lung regulator #1008 and cartridge belt weights. As an actor he was no longer allowed to dive or fly planes. During this time, Jacques Cousteau was a friend of Rene Bussoz, the owner of the dive shop in Westwood. Jacques Cousteau sent some of his original Aqua Lung equipment to Rene. The set my uncle gave me, steel twin 72s; 1800 psi, was likely two of the first tanks that Cousteau had shipped to Rene. The story was that Cousteau later asked if Rene needed more tanks and Rene said, “I don’t think so, I think we’ve saturated the market.”

I took the gear and a very good friend down to Palos Verdes. In those days inner tubes were deflated so they would go through the kelp and waves and be used as dive markers. I took the commonly used inner tube with a line so he could watch me. When I came back up he was very concerned. The tube had dropped below the surface and he didn’t know where I was. My friend was very relieved to see me. I realized right then I needed to get some training and at that time there wasn’t much around.

I went to Los Angeles County to get some help setting up a SCUBA course. There was some diving equipment lying around the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) left by Conrad Limbaugh and Andreas Rechnitzer after they went down to San Diego. Clint Degn and Mike Brock came out and did the first scuba course at UCLA with myself and other staff members in the class. I was asked then to participate in the Los Angeles County Underwater Instructor Certification Course and became a Los Angeles County SCUBA Instructor in 1964. At that point we also developed an instructional staff, training program and diving safety control board at UCLA.

I thought diving was wonderful and learned what had to be done in order to perform properly and safely. My motivation was that diving was complicated and wasn’t something you fooled around with. It needed to be made safe. This was the time when I first appreciated the complexity of diving as a sport. Like it or not you have to get involved in some science, acquire a number of special skills and techniques, as well as develop specific fitness to get through the surf and dive. It was a great time.

How would you describe your sense of adventure?

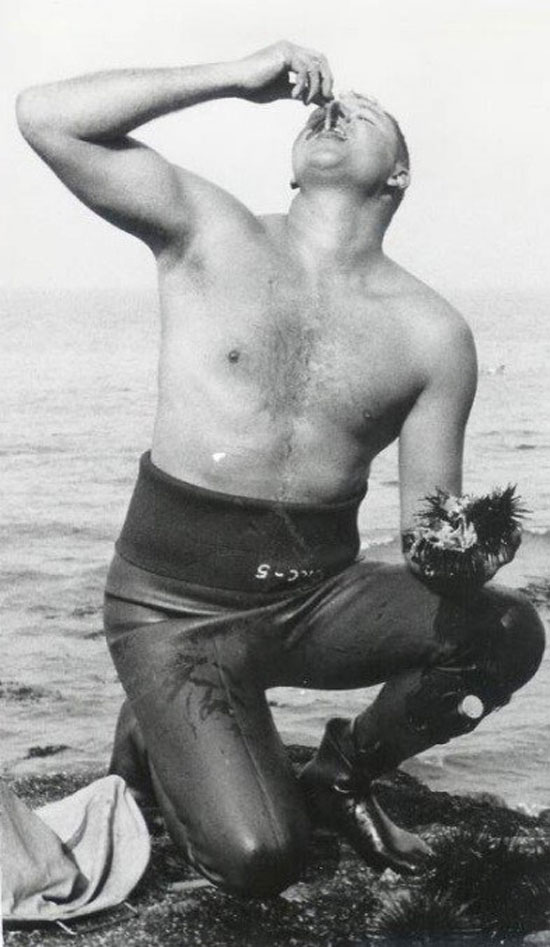

I did a lot of free diving with the skin and scuba club at UCLA. I tried to get out once or twice a week to an area in the bay where we could go to get lobster, abalone, scallops and halibut. In our home, lobster was cheaper than hamburger. You never had any problem going out and getting as much as you wanted. I filled milk cartons with two lobster tails, added water, and froze them in a block of ice for later consumption.

We had a tradition at the UCLA club we called “Bouillabaisse”, but it was really a big fish stew. Bouillabaisse was a social event where everyone could tell their sea stories. For our club meeting we would go to the Pioneer Bakery and get day-old French bread for a dime a loaf. Everyone would go diving and bring stuff in fresh. We filled a 20 gallon Army surplus pot with onion, garlic and butter and threw everything in the pot except the abalone which was fried. No alcohol was allowed on campus but Gallo zinfandel was excellent and very inexpensive at the time. We used the kitchen at the recreational center and started cooking at about three in the afternoon. We also cooked out on the beach up at Zuma. Jack McKinney, Ralph Osterhout, and Paul Tzimoulis also may have been there from Skin Diver Magazine to cover the story. There wasn’t a lot of game that day but we managed to get some halibut, clams and a big crab and put something together. Around that time, I think I wrote an article about how to clean a halibut.

As you transitioned from the thrill of the hunt to underwater videography what is the most amazing thing you’ve seen underwater?

During the 1970s, we were out gathering clams at about 30 feet underwater at Zuma Beach and this huge Grey Whale came in to engage in what I call “dusting”. We watched for 12-to-15 minutes as the whale swept in and rubbed its body against the clam beds to scrape away barnacles and other things. Those were the days where you could go to Zuma Beach and in about five minutes get about five five-inch clams. The whales were going north at the time.

Your interest in athletics blossomed at an early age. What sports and recreational activities did you enjoy while growing up?

I grew up playing sports; football, baseball, volleyball, and basketball. I ran track, played badminton, and loved tennis and swimming. When they dammed part of the river in my home town to make a swimming area I was the first lifeguard (1945 I think).

Only 8 to 13% of the population in the United States earned a Bachelor’s Degree or better in the 1950s and in your home state of North Dakota the percentage was nearly half. Was there someone in your life that encouraged you to pursue your education or helped make it possible in some way?

My uncle was the YMCA director at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks. I was both an All State Championship Football and Basketball athlete in high school. I was invited to go the University of North Dakota where I played four years of college basketball. I lived in a YMCA while in college doing night work when not involved in sports. After returning from Korea I also played on a National Collegiate Championship Volleyball team at UCLA.

Thank you for your military service. During your 15 years as an officer in the Army, you were involved in the Korean conflict. Like many, being drafted took you away from home and your civilian career path. While military service permanently changed the life direction for others, after your service how did you continued your education and profession along the same path?

It never occurred to me to do anything else. Good luck and opportunities just seemed to have come my way. Although I was drafted, during boot camp I was selected as trainee of the week at Fort Ord, California and got my picture taken with the General. After that I was promoted to Sargent, then selected for Officer Candidate School and was assigned to a battalion for anti-aircraft defense at March Air Force Base. I was only there for a few months before going to Korea. On the way to Korea I was trained in chemical warfare (CBR) in Japan. When I arrived my unit was on the main line of resistance and I was assigned a platoon of self-propelled anti-aircraft artillery (AAA). We were using them in direct support of infantry. We had eight armored vehicles; four had twin 40 mm cannons on them and were full track, and four were half-track with four 50 caliber machine guns. I was later selected to go to a tactical air control squadron. There was some difficulty with close air support and they were taking young officers off the line and sending them to this squadron where old AT6s, converted advanced training aircraft, had rockets loaded under the wings. The units were called Mosquitoes. We conducted 28 missions putting in air-to-ground strikes with aircraft with either the USS Boxer or USS Philippine Sea aircraft carriers. We would mark the targets with colored smoke and then direct the ordinance as an artillery strike. When I returned home, I used the G.I. Bill to continue my education. I also continued as a reserve officer and became a General’s aid for several years.

You began diving nearly 20 years before the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA) of 1970 and 30 years before organizations such as Divers Alert Network (DAN) were formed in the 1980s. You were a part of the birth of both modern day diving and fitness developing principles and safety standards, and instructions for the use of diving equipment. During this period of discovery, was there a lot of interest and collaboration? Did you and your contemporaries see what the diving industry might be – as it is today? Or was your extensive series of projects, organizations, standards and more than 125 publications a necessity of the time and simply the job in front of you?

The most problem solving for diving came about through underwater physiology symposiums – the first one was in the 1960s. The symposiums related to some of the things I was involved with at the Naval Medical Research Institute Behavioral Sciences Laboratory with Art [Dr. Arthur Bachrach]. The seed that grew into my full interest in diving fitness was reinforced by the symposiums. This was particularly interesting to me because early on in my career I realized fitness is a very complex issue. It’s not just exercise. The first thing that became obvious to me, and a part of my research, was answering the question “fitness for what?” Once you made that determination then you had the biomechanical, physiological, methodological, and psychological with a subset of medical. It was a fascinating switch in perspective to recognize that we make these specific adaptations and as a consequence we need to know in specific detail what are the requirements on the person. How much are we affected by the equipment, the tools, and the functional muscle groups involved in performing different activities. Swimming during diving, for example, is in quite a different manner than what people are used to. Most swimming involves in a large portion upper body rather than develop a kicking style. Just the adaptation to the swim fin is a major undertaking. The four major barriers to performance, biomechanical, physiological, methodological, and psychological, as well as medical issues are all involved in the performance. All of the above are limiting factors to what you might expect a diver to be able to do. We all make specific adaptations to the imposed demands of the environment (the S.A.I.D. Principle). Being able to do the analysis, we can identify the functional muscle groups and develop the strength and endurance for the type of diving, diving logistics and conditions of the day. One of my concerns is that folks want to develop fitness programs solely around their strengths rather than the activities they need to perform.

Read Dr. Glen Egstrom’s Bio:

http://www.internationallegendsofdiving.com/FeaturedLegends/Glen_Egstrom_bio.htm

As a kinesiology professor at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), the research you conducted included early generations of diving equipment, human physiology and biomechanics underwater, along with cognitive and stress analysis during diving. One of your many publications is the book you co-authored with Dr. Arthur Bachrach, titled “Stress and Performance in Diving”. What do see as your most significant contribution to modern day dive equipment? What do you see as your most significant contribution in understanding performance and stress of divers?

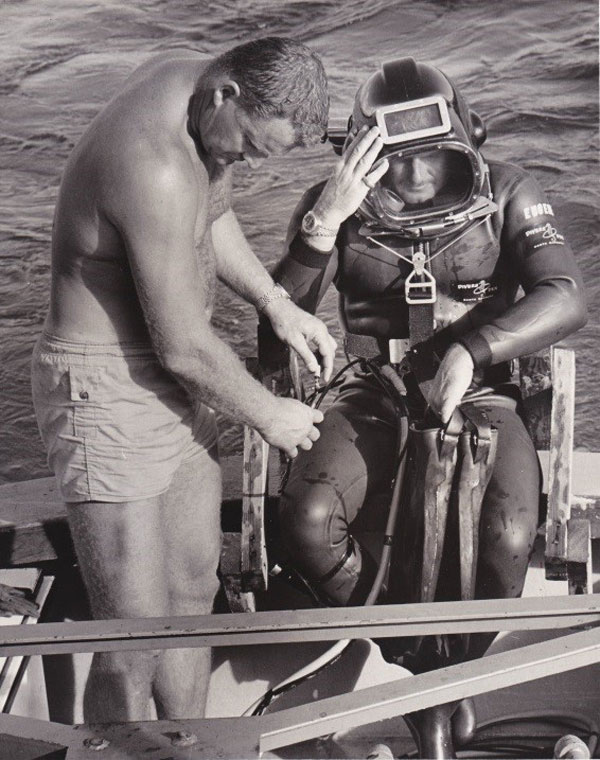

As part of developing underwater work tolerance tables, we built an underwater ergometer and set up an obstacle course in the swimming pool. We had a large 40 x 50 inch window and cameras and tried a number of different jobs and obstacles where the task needed to be completed while maintaining buoyancy. We also worked on buoyancy control and weightless training with early astronauts.

Get the Book by clicking HERE.

Did the OSHA Commercial Diving Exemptions, which allowed separate safety standards for scientific diving, affect your work in the field of diving physiology and biomechanics? Did they open the door to the future of recreational diving?

Oh yes. During this time the American Academy of Underwater Science and many leaders in academia and diving came together and worked for years to get an exception. As a result of the struggle for scientific diving, recreational diving would have happened but be much more restricted and may not have grown as much because of the restrictions.

In addition to search and rescue diving with law enforcement agencies, you have dedicated yourself to public safety in roles as safety officer, course director, author, researcher, expert witness and public speaker. Your public speaking includes being on the teaching staff of more than 50 dive medicine courses for continuing education of diving physicians worldwide, instructing dive professionals, and presenting at dive clubs. What did you find was the biggest challenge and solution in relating a message of safety to both professional and recreational divers?

The biggest challenge was to develop the perspective that if diving is not done properly it is a dangerous activity. Still we lose more people every year than we should because of the lack of enlightened experience. Divers get into situations where they are not adequately prepared to cope with the specific problems they encounter. One thing I noticed when working with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Emergency Services Dive Team is that some fit divers begin to think they are invincible and are regularly proven wrong.

More and more as we have watched the development of recreational scuba we have gotten away from the basics. My recognition of the complexity of diving increased with the realization that you had to deal with the individual aspects of a person’s comfort level. Diving is the best conditioning program for divers. If you can’t dive regularly, you need to be aware of the specific adaption for diving in different environments and with different equipment. All of it needs to be specific to the dive that you are going to make. Too many people make the assumption that because you dive in one condition and get along all right that you can change over to another condition. One example is the difference between wet suit and dry suit diving. If you want to do both you have to follow the protocols and adapt to each technique.

Your lifetime of commitment in this field is remarkable. What drive’s you and how do you re-boot?

It is what stimulates me. For the diving activities there’s no need to re-boot.

You shared that “you felt that exposure to students is one of the most enriching learning experiences that one can have on this planet”. As a physical education instructor, coach and mentor you role modeled and inspired youth from many walks of life. One opportunity was as a board member of the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society. Are these scholarship opportunities important to the youth of today and what area of expertise do you recommend?

I have been involved with the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society (OWUSS) over forty years and had the good fortune to be a founding member. A bunch of us were standing on the deck of a boat in San Francisco Bay; Joe MacInnis and Joy Markstahler, Lee Somers and a number of others; when somehow the conversation turned into “what can we do with the funds from a successful show.” Everyone agreed that the scholarship idea was great. It started off with one scholar and now we have scholars from North America, Europe and Australasia and are looking at both Asia and South America. We developed an internship program which is like mini scholarships. Interns go out perhaps for just the summer and do the same things. We have had dozens of interns. Many have gone into very prestigious positions such as at National Geographic and the Smithsonian Institute.

If a young person of today has the gumption, I recommend something in the area of well-founded diving programs. Each diving group feels that they are doing the best job of anybody out there, but there could be a more centralized exchange of knowledge and ideas. In diving, it is difficult to retain a lot of the people we train. It is really because they are not fit to dive – realize it – and drop out. Overall, the diving population could enjoy diving a lot more if we didn’t have an incredible focus on deep diving. There is so much diving shallower than 60 feet that is some of the best diving you’ll ever see.

You are married to Donna 65 years and have three adult children. Does your family dive and were they able to travel with you when work took over and under the sea?

Donna was my dive buddy until she reached age 75. My eldest daughter was a UCLA lifeguard and became a scuba instructor. My son dives occasionally and is a world class kite surfer. My youngest daughter loves the water although doesn’t scuba. I did not have the opportunity to take my family with me on most of my travels.

How have you maintained your health and fitness throughout life and has it changed over the years. What is your favorite fitness activity today?

My favorite activity is diving; being in the water. I love to swim, enjoy underwater videography and SCUBA diving in clear, calm water. Currently, it has been a tough couple of years with a number of injuries and I am looking forward to getting back to diving. I miss it so much. I look at diving as hyperbaric therapy. I have done a lot of research. Because you have a higher partial pressure of oxygen you have effectively doubled the pressure of the oxygen that you carry in your tank at 33 feet. As a result, I have felt for years that this is why I have had so little in the way of respiratory infections and diseases that came around. So much so, that when I can’t dive underwater I am diving in a hyperbaric chamber once to twice each week and it does make a difference.

What observations have you made about the health and physical fitness of divers over the past 50 plus years?

It has been my experience with the advent of less local club diving and more resort diving I have seen a definite change in the fitness and comfort level of divers. There is a difference between diving and surviving underwater. I see more underwater survivors and fewer divers.

What would you like to convey to the divers of today?

Get into diving – get a good diving background and it will change your life. It has certainly changed mine, as well as the lives of friends and students I have worked with during the past 50 years.

Where would you like to see diving going in the future?

I would like to see the menu for divers and diving specialties increased so people would dive more. Divers don’t hone their skills as much as they should. They go down and drift along a wall and all they are really using is their eyes and finning with their hands and feet. It is a different type of comfort we should be striving for. Stress is still one of the biggest issues in diving. It has been my experience that a fit diver is a comfortable diver. Get the identical elements for the functional muscles that are used in diving into your exercise routine and dive as much as possible in order to make the most effective specific adaptation to the imposed demand.

Story by Gretchen Ashton, photos provided by Dr. Glen Egstrom

.