In 2014, a 13-minute horror/comedy movie called “Hellyfish” was released. This movie short, which went straight to digital streaming, told the story of a missing nuclear weapon and the ecological destruction the leaking material created. The main focus of this movie are the hordes of enormous man-eating jellyfish spawned by the nuclear waste. An Oscar nominee it wasn’t!

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher P. Weaver

Fortunately, divers don’t have to contend with the radioactive beasts depicted in this movie, but Jellyfish are in the waters we explore and it is best to understand them even as we marvel at their beauty.

The Biology

Jellyfish are found in all the world’s oceans, from shallow coastal waters to the deep abyss. While most can inflict a relatively mild but painful sting, some are harmless. Others, however, are extremely dangerous and the toxins in their stings can be fatal. Collectively, Jellyfish, also referred to as Jellies or Sea Jellies, belong to the biological family known as Cnidaria, which contains 11,000 different species of Jellyfish, hydroids, sea anemones and corals. Comb Jellies, which are related to Jellyfish, belong to a separate order known as Ctenophora.

Many divers are familiar with the intimidating Portuguese man o’war. Although equipped with tentacles and stinging cells, this is not a true jellyfish. Rather, the Portuguese man o’war is actually a siphonophore. Like all siphonophores, it is a colonial organism: each animal is composed of many smaller units that hang in clusters from under a large, gas-filled bladder called the pneumatophore. The bladder is used as a sail and is the most conspicuous part of the animal.

The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish carries potent stinging cells in its tentacles

Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals, although a few anchor themselves to the seabed. Typically, Jellyfish have an umbrella-shaped main body known as the bell, and a collection of trailing tentacles on the underside. Using pulsating contractions, the bell can provide propulsion through open water. The tentacles are armed with stinging cells known as nematacysts and may be used to capture prey or to defend against predators. These stinging cells are spring-loaded and deploy on contact. They remain active and capable of delivering a sting even when detached from the main body, which is why even dead Jellyfish that have washed ashore should be handled very carefully.

The life cycle of a Jellyfish is complicated, but the phase that most people encounter is known as the Medusa phase. This is normally the sexual phase, which produces free-swimming larvae. The larvae disperse and search for a site to attach to where they begin the sedentary polyp phase. At sexual maturity, they detach and begin wandering the open water as a medusa. The medusae of most species are fast-growing, and mature within a few months and die soon after breeding.

An early medusa stage of a jelly swims by on a black water dive in Hawaii

Jellyfish have been in existence for at least 500 million years, and possibly 700 million years or more, making them the oldest multi-organ animal group. The smallest Jellyfish have a microscopic bell measuring 0.5 millimeters (1/32 of an inch). The largest Jellyfish, the Nomura jellyfish from Japan and the waters of the western Pacific, can have a bell that reaches 2 meters (6 ½ feet) and weigh more than 200kg (440lbs). The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish is often referred to as the longest animal in the world, with tentacles that can extend as far as 36 meters (119 feet)!

The vast majority of Jellyfish inhabit the marine environment, but there are a few species that are found in fresh-water eco-systems. Most Jellyfish, when they are in the medusa stage, live off the ocean floor but there are some species, like the Upside-down jellyfish which generally lies on the bottom of shallow lagoons with their bell facing downwards.

Jellyfish are carnivorous, feeding on planktonic organisms, crustaceans, small fish and other Jellyfish. Jellyfish themselves are part of the diet of sea turtles, tuna, sharks, swordfish and even some sea birds. However, the reality is that there are few animals that prey on jellyfish; they can broadly be considered to be top predators in the food chain.

Often, divers will find Jellyfish in relatively small numbers in the water. However, blooms of Jellyfish can occur and a large aggregation of Jellyfish has come to be known as a “smack”.

Encounters

Jellyfish can be found on almost any dive anywhere in the world. While most of our encounters with these creatures have been relatively mundane, some are note-worthy.

For example, while diving on the wreck of the USS San Diego off New York’s Long Island, we found a rather large Lion’s Mane Jellyfish drifting slowly through the water column as we were descending the down line to the wreck. This species, with its red coloration and hefty clumps of tentacles beneath its substantial bell, present a fearsome appearance. And for good reason: the sting of a Lion’s Mane, while usually not fatal, is quite painful.

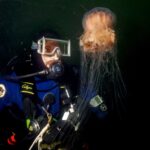

Because the USS San Diego lies in 120 feet of cold North Atlantic water, we were safely ensconced in dry suits and dry hoods and we felt emboldened to examine this creature at closer range than would normally be advised. The resulting photo shows the size in relation to a diver of this impressive organism.

Author Christopher Weaver examines a Lion’s mane Jellyfish while diving on the USS San Diego wreck off New York’s Long Island

While exploring the Mediterranean Sea off the shores of Malta, we encountered two vastly different species of Jellyfish. As the waters of the Mediterranean warm, more and more Jellyfish are migrating west into the central parts of the sea.

Of these, the Purple Mauve Stinger is of more concern as it packs a nasty sting and can be dangerous. These jellyfish are migrating into the Mediterranean in increasing numbers, as well as other bodies of water around the world. Recently, a large gathering of this species invaded the coastal waters of Long Island in New York, and so many swimmers experienced painful stings that the beaches were closed temporarily until the jellyfish departed.

Larger populations of other species, such as the Fried Egg Jellyfish, are also being spotted near Malta, although the Fried Egg Jellyfish is beautiful and does not sting! On our dives in Malta, we saw this species on every dive and even observed large bristle worms feeding on the Jellyfish themselves.

Bristle Worms prey on jellyfish, like this Fired Egg Jellyfish in Malta

In Alaska, as part of an expedition to find Salmon Sharks, we also hoped to find large blooms of Moon Jellies. These large gatherings, or smacks, are mesmerizing experiences as divers can fully immerse themselves in the gelatinous aggregation of jellies. The moon jelly differs from many jellyfish in that they lack long, potent stinging tentacles. Instead, they have hundreds of short, fine tentacles that line the bell margin. The sting has no effect on humans.

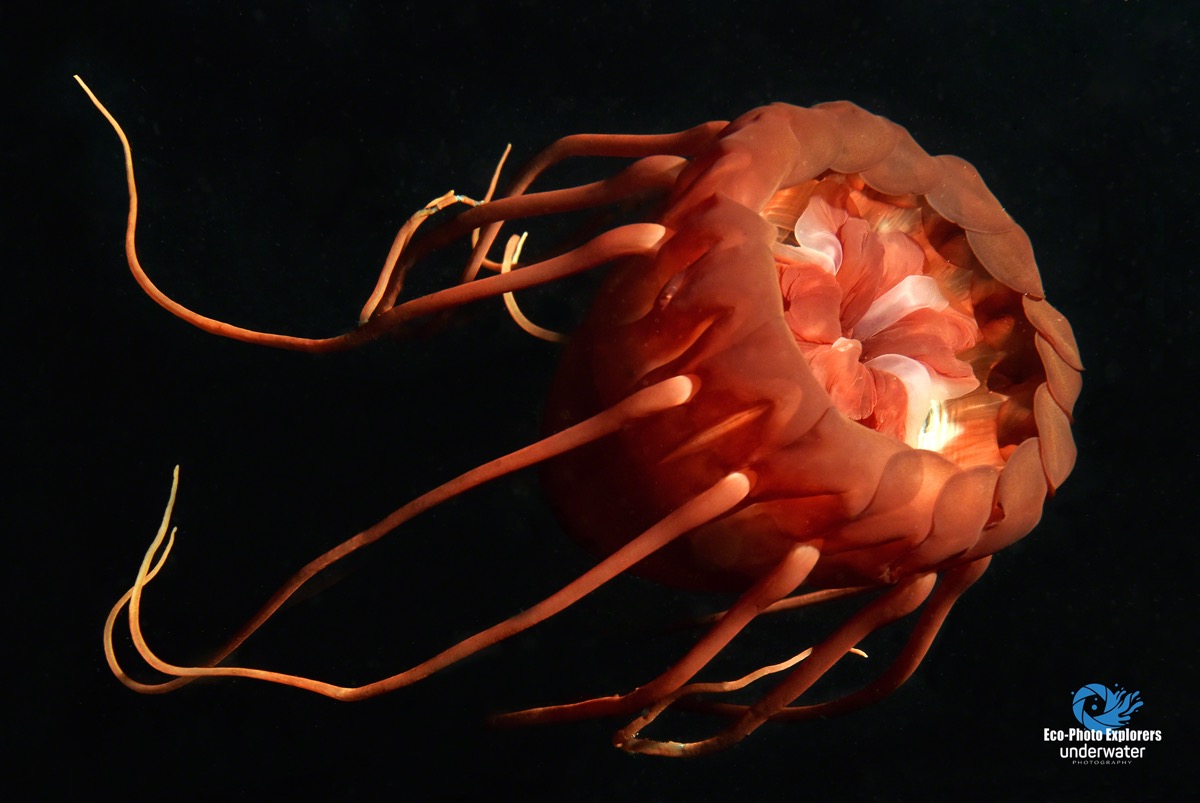

In addition to the Moon Jellies, we also found Lion’s Mane Jellyfish in Alaska and, perhaps one of the most photogenic, the Northern Sea Nettle. The Northern Sea Nettle can reach 60 cm (2 ft) in diameter with tentacles growing up to 3 m (10 ft). These handsome jellyfish can be found at depths of up to 100 meters, where it feeds on copepods, larvae of crustaceans, small fish, large zooplankton, and other jellies. The sting of the Sea Nettle is mild, although it can cause serious skin irritation and burning.

On a different expedition in Norway, we found ourselves diving with the alien-looking Helmet Jellyfish, which is a luminescent, red-colored jellyfish of the deep sea while exploring the fjords in search of Ghost Sharks. This jellyfish is found in depths up to 2700 meters (8800 feet) and is adapted to its dark environment. Sunlight seems to be very harmful to adult helmet jellyfish, and even deadlier to younger helmet jellyfish, which keeps them in deep water during the day. But at night, these animals rise to shallower depths to feed. Our encounters with the Helmet Jellyfish took place in 30m (90 feet) of water well after midnight on a cold, rainy evening.

A red Helmet Jelly photographed in a Norwegian fjord

In the darkness of the nighttime fjord, we concentrated the beams of our dive lights to look for the Ghost Sharks, another deep-water species that rises to shallower depths to feed at night. Suddenly, a red bulbous form passed through the distant fading beams of the dive light. We quickly approached, and were rewarded with a close encounter with the Helmet Jellyfish. This was a pleasant surprise on the way to finding the Ghost Sharks, which we eventually did. It was well worth the effort of an after-midnight shore dive in the cold sleet and rain!

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher P. Weaver

On the big island of Hawaii, a dive known as “Pelagic Magic” will often bring divers face to face with some of the smallest forms of Jellyfish. It is a dive that requires some getting used to as the boat motors out to a random spot in 3000m (6000 feet) of water under the blackness of night. There, divers will descend to about 20m (60 feet) and, while attached to a down line, begin to observe and photograph the myriad planktonic creatures that begin to float by. It took several moments for our eyes to adjust to the darkness, master the technique of using lights to highlight tiny transparent organisms in the massive expanse of black ocean water, and then to utilize the camera properly to capture images of these creatures. Larval fish, crustaceans and zooplankton pass in front of the camera lens, along with different species of small Jellyfish.

Black water diving is not for the faint of heart, and we were happy the Oceanic Whitetip Shark that came to visit waited until after we were out of the water. Or so we think!

Jellyfish Lake in Palau is world famous for its aggregation of migrating Golden Jellies

In Palau, located in the heart of Micronesia in the western Pacific, a marine lake is known as jellyfish lake because of large populations of Golden Jellyfish that inhabit the waters here. Each day, these hordes of jellyfish migrate according to the movement of the sun. Snorkelers who trek here can experience swimming amongst the jellies, which carry such a mild sting that it generally cannot be felt. In recent years, significant die-offs of the jellies have occurred and biologists have attributed these events to warming waters due to climate change. For us, the experience of swimming among the multitudes of harmless jellies years ago was a beguiling experience.

Our first encounter with a Portuguese Man O’War Jelly came on one of our earliest expeditions. We were exploring the waters off Belize when we spotted one drifting in the shallows near Ambergris Caye. Being young and a bit naïve, we posed for images next to the creature ignoring the possibility of a painful sting. We did use those images on our website for years, though!

It wasn’t until several years later when one of us received a sting from a Portuguese Man O’War while snorkeling in the Dry Tortugas of Florida. An audible “snap” was heard when an errant tentacle made contact with the part of the forehead exposed to the water, delivering an instantaneous and very painful sting. We got out of the water immediately, but a dreadful feeling of dizziness coupled with chest heaviness, rapid breathing and queasiness followed. This lasted for several hours before it completely resolved. The Portuguese Man O’War is not to be fooled around with.

First Aid

Contact with a jellyfish tentacle can trigger millions of nematocysts to pierce the skin and inject venom, but only some species’ venom causes an adverse reaction in humans. The effects of stings range from mild discomfort to extreme pain and death.

For common jellyfish stings, the following first aid is recommended:

- Carefully pluck any visible tentacles with fine tweezers.

- Soak the skin in hot water in the temperature range of 110 to 113 F (43 to 45 C). It should feel hot, not scalding. Keep the affected skin immersed or in a hot shower until the pain eases, which might be as long as 20 to 45 minutes.

- Apply 0.5% to 1% hydrocortisone cream or ointment twice a day to the affected skin until symptoms subside.

Despite some long-standing myths, the following should not be attempted:

- Scraping the skin to remove stingers

- Rinsing the site with human urine

- Rinsing with cold, fresh water

- Applying meat tenderizer

- Applying alcohol, ethanol or ammonia

- Rubbing the affected site with a towel

- Applying pressure bandages. Pressure bandages have been shown to trigger any remaining nematocysts to inject more venom.

The Box Jelly, found in warm, tropical and subtropical waters around the world, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region, is among the most dangerous Jellyfish in the world. Also known as Sea Wasps, their sting can be lethal. The Australian Box Jelly is generally accepted as the most dangerous Jellyfish in the world and its sting can cause death with minutes.

When a Box Jellyfish sting occurs, prompt medical attention, including CPR and other life support measures, especially in cases of severe reactions or cardiac arrest is essential. The best immediate treatment is the application of vinegar (4–6% acetic acid). Vinegar has been shown to permanently deactivate undischarged nematocysts, preventing them from opening and releasing additional venom.

Author Michael Salvarezza examines a Fried egg Jellyfish up close

The Future

Changes in the Earth’s climate are having a significant effect on populations of Jellyfish. As the oceans warm, tropical species are migrating further north (and south) and invading regions where they previously never existed. These newcomers are disrupting the food web as their populations have exploded. Jellyfish are gorging on copepods and other planktonic species that comprise the base of the highly inter-related food chain, removing the available food for other species. Although some species prey on Jellyfish, most do not and the expanding populations of Jellyfish are crowding out other species.

Dangerous species of Jellyfish are showing up in waters where they had previously never been seen, inflicting painful stings on unwitting swimmers, snorkelers and divers while disrupting the marine ecosystems they are living in. Jellyfish invasions are a symptom of the larger problem of climate change.

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher P. Weaver

The future for jellyfish remains uncertain. Will they invade all corners of the world’s oceans? Will the ocean become just a mass of gelatinous organisms? It’s too early to say for sure, but Jellyfish will continue to present a clear danger to those who encounter them and as new species arrive and their numbers increase, that threat grows larger every year.

One thing is for sure: look but don’t touch these amazing, beautiful but potentially dangerous creatures.

- Author Michael Salvarezza examines a Fried egg Jellyfish up close

- A delicate planktonic jelly swims at night off the big island of Hawaii

- This jellyfish was photographed in the kelp gardens of Namsfjord in Norway

- Comb jellies have a distinctive bioluminescence

- Black water dives expose divers to myriad microscopic creatures

- An early medusa stage of a jelly swims by on a black water dive in Hawaii

- Author Christopher Weaver examines a Lion’s mane Jellyfish while diving on the USS San Diego wreck off New York’s Long Island

- A red Helmet Jelly photographed in a Norwegian fjord

- The Helmet Jelly is a bulky jellyfish with thick tentacles

- The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish has a robust body and long tentacles

- A Moon Jelly near the surface off West Palm Beach, Florida

- The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish carries potent stinging cells in its tentacles

- The four roughly circular shapes visible through the transparent bell of a Moon Jelly are its reproductive organs

- A beautiful Moon Jelly photographed in Alaska’s prince William Sound

- The Lion’s mane Jellyfish has some of the longest tentacles of all known jellyfish

- Bristle Worms devouring the remains of a Fired Egg Jellyfish in Malta

- The Northern Sea Nettle feeds on copepods, larvae of crustaceans, small fish, large zooplankton, and other jellies.

- The Purple Mauve stinger is a dangerous species that has been moving into new territories as the oceans warm

- Jellyfish Lake in Palau is world famous for its aggregation of migrating Golden Jellies

- Bristle Worms prey on jellyfish, like this Fired Egg Jellyfish in Malta