We all learn about buoyancy control in our entry-level training. Yet we can be perfectly neutrally buoyant, and still stir up the bottom enough to obscure visibility. Why? Because, in addition to practicing buoyancy control, we must also strive to master neutral trim—to become and remain horizontal within the water column.

——————————————————-

Words and Photos by Jeffrey Bozanic

——————————————————-

Technical diving is—in large part—about refining buoyancy control and other dive techniques. It generally takes many dives to perfect the art of maintaining neutral buoyancy. Along the way, most of us learn to use our lung volume as fine tuning buoyancy control devices (BCDs), inhaling a little to move slightly up in the water column, and exhaling to move downward. However, I have seen many good recreational divers obtain perfect buoyancy, but continually obliterate visibility due to body positioning.

The term “buoyancy” refers to our tendency to float or sink—to move up or down in the water column. Most of the time, divers strive to be neutrally buoyant, so that we are not struggling to maintain a particular depth.

Buoyancy vs. Trim

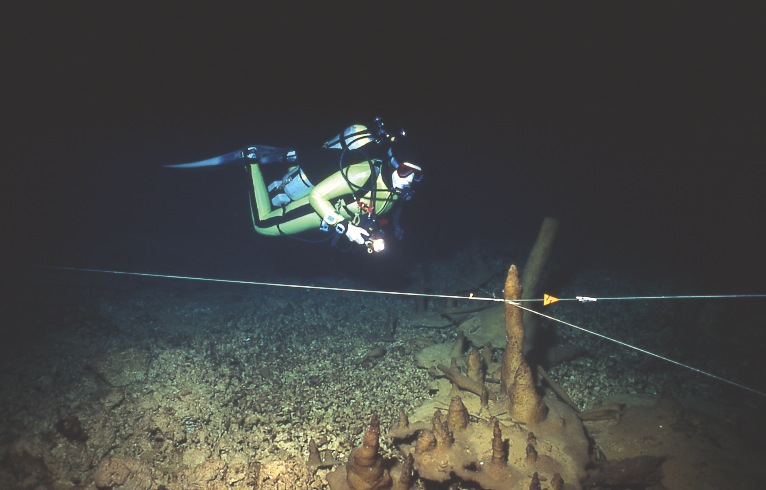

Trim refers to the attitude of the body in the water. In most situations, a horizontal position is best. This stance minimizes drag as you swim and maximizes thrust as you kick, making you a more efficient diver. It is also the first step in keeping your fin kicks from disturbing the bottom. We call this a neutral trim position.

When you are completely relaxed in the water column, what orientation do you naturally fall into? For most of us, it is an almost-vertical position, with the head up, and the feet down. As we begin to swim, this orientation changes to about a 45-degree angle in the water. In most open water diving conditions, this is fine.

As open water divers, we generally do not need to swim extensive distances during a dive, so a little drag is acceptable. Similarly, it is not a significant safety concern if we stir up the bottom a little in a recreational diving situation, because we can merely swim upward until we are in cleaner water. However, these options change in technical diving situations.

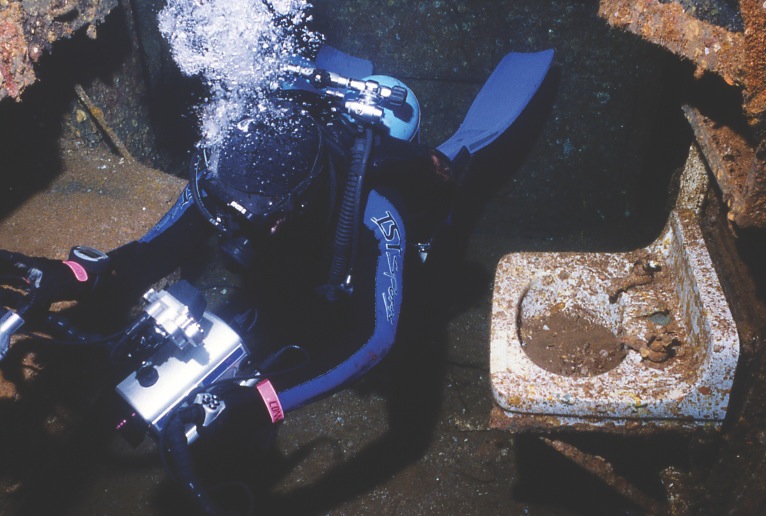

Many technical diving activities—such as cave or wreck diving—involve swimming long distances. Excess drag and loss of propulsion efficiency leads to longer bottom times and extended decompression risk. It also increases diver fatigue, leaving the diver less capable of handling emergency situations involving strenuous responses, which also boosts decompression stress.

Additionally, many technical diving environments are silt-laden. Caves, wrecks, mines, and deep bottoms are often very silted. Divers in enclosed spaces may not be able to rise up off the bottom to regain visibility, as they may be constrained by ceilings, or because they might lose the reference of navigational aids, such as lines or landmarks. The ability to move without disturbing the bottom is a critical skill in most technical diving environments.

Achieving Neutral Trim

Most of us have poor trim because of our equipment. We begin training with BCDs that have the largest part of the volume high around our necks. This helps us keep our heads above the water when inflated at the surface, a benefit for new divers. We are taught to attach the BCD high on the tank, so as to avoid hitting our heads on the tank valves while swimming. We wear weights on a belt or in pouches near our waistlines to make them easy to ditch in an emergency. And most of us begin diving with aluminum cylinders, which are lighter than steel cylinders. All of these things hurt our efforts to achieve neutral trim.

Think of your body as a seesaw. The fulcrum—or central point of balance—is roughly at the abdomen. If we want to achieve a neutral trim position, we must balance the positive and negative forces acting on each side of the fulcrum.

Consider how you learned to dive, as summarized two paragraphs above. BCDs add lift high on the body, pulling it upward. Even given its small volume, the mask does the same thing, aided by the leverage it exerts from its position so far away from the fulcrum of the body’s “seesaw.” Attaching the BCD at the highest part of the cylinder drops the bulk of the cylinder weight lower on the body, dragging the lower part down. Our weights are on the lower part of the body, further dragging it down. We commonly start diving with more weight than we need, because anxiety causes us to hold more air in the lungs than when we are relaxed. Ankle weights—often used to help new drysuit divers keep from turning upside down—also compound that problem.

So, what’s the solution?

Start by dropping weight. Even experienced, comfortable recreational divers generally dive over-weighted by two to seven pounds (1-3 kg). This results in more air in the BCD, dragging the upper half of your body toward the surface, while the weight belt, drags the lower half of the body downward. Over-weighting in itself can make it nearly impossible to achieve neutral trim. You must eliminate this excess weight before refining further.

Next, attach your BCD lower on the cylinder. This has the effect of moving your cylinder up on your body, shifting the weight over the fulcrum. This will help bring your head down. It may be uncomfortable at first, but you should quickly adjust to it.

If you use a drysuit, eliminate ankle weights. Learn to use your body positioning to prevent air from entering your feet, which can cause a potential inverted ascent. In fact, I almost always purposely kick a little air into the feet of my drysuit to help keep my feet elevated, even if other factors like weight-belt placement adversely impacts my trim position.

Equipment Modifications

New equipment may also assist in achieving proper trim. Consider buying a BCD that has minimal volume around the neck or upper part of the unit. This is one of the reasons that many technical divers use wings instead of the jacket-style BCDs commonly used in recreational diving. Lighter fins may also reduce the downward force exerted by heavy fins.

Equipment that distributes the weight more evenly along the entire fulcrum may help as well. Steel cylinders may allow you to remove some weight from your belt or weight pouches. Again, technical divers often use a backplate system instead of a jacket-style BCD tank mount. This allows them to select a backplate suited to a particular diving environment. In cold water, where greater thermal protection is required, technical divers often use a heavy stainless-steel backplate, which adds weight in a well-distributed fashion. In warmer water, an aluminum or composite plate may be used instead, eliminating excess weight.

Finally, one of the most effective means to alter trim is to change the placement of your weights. Moving weights from the waist to a point higher on the body can have a great impact on trim. Many divers add weights to the shoulder straps of their harness. Others may fasten them to bands high on the cylinders. I routinely insert them under the housing, high inside my rebreather. And sometimes clip weights may be used to effect temporary trim correction.

Be aware, however, that many of the options I have suggested in this column have caveats and tradeoffs. BCDs with minimal volume high on your body may result in you floating in a face-down position on the surface, which can be both uncomfortable and even dangerous in some situations. Fixing weights to your body without the ability to jettison them in an emergency could lead to drowning. While non-detachable weights are completely appropriate in overhead environments, you may wish to wear a portion of your weights in a manner that allows you to ditch them if you are diving in open water.

Your goal should be to look like most fish in the ocean—neutrally buoyant, and completely horizontal. You will find that the ability to maintain neutral trim in recreational diving situations will also increase your enjoyment as you glide more effortlessly over silted lake bottoms and deftly avoid causing accidental damage to the reef structures you encounter.

——————————————————-

Words and Photos by Jeffrey Bozanic

——————————————————-

.