Diver, Beware.

Every dive site has its lore.

Some are famous for gorgeous underwater topography. Others for their noteworthy marine life. Still others are known for being great training spots.

And then, there is Monastery Beach in Carmel, California.

True—Monastery is well-known for its stunning underwater landscape, astride a subaquatic canyon that drops off thousands of feet into the Pacific. It also hosts a variety of impressive fauna, from Humpback whales and blue sharks to frolicking sea lions. But above all, Monastery is known as one of the most dangerous dive sites on the Central Coast.

True—Monastery is well-known for its stunning underwater landscape, astride a subaquatic canyon that drops off thousands of feet into the Pacific. It also hosts a variety of impressive fauna, from Humpback whales and blue sharks to frolicking sea lions. But above all, Monastery is known as one of the most dangerous dive sites on the Central Coast.

You might think that a reputation like that would detract from this site’s appeal. Somehow, however, Monastery manages to draw a steady stream of divers (and non-divers) to its seductive white sands. And year after year, its roiling undertow claims at least a handful of victims—about 20 since 2004, according to local news accounts.

The site is so infamous, there is even a surf exit strategy named after it: “The Monastery Crawl.” Local scuba instructors routinely teach this maneuver to new divers, even those training at different sites. It is common to see student divers in buddy pairs, regulators in their mouths, unceremoniously crawling on hands and knees out of the surf.

“I don’t dive Monastery alone,” says PADI instructor Jim Ernst, who provided the photos for this article. “Someone who has experience at Monastery can look at the surface of the water and just read what the current and wave modules are saying. Sometimes it looks flat as a lake to me, but Ericson (Ericson Reduta, local diver and underwater photographer) says ‘no, we’re not diving it today.’ “

Monastery sign designed by Harry “Doc” Wong, D.C., a well-known local technical diver who is also the President of the Northern California Oceans Foundation.

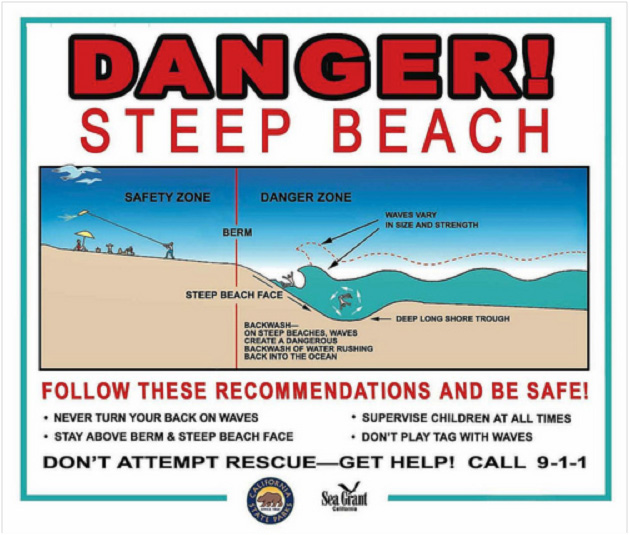

Ernst isn’t kidding. The site is covered with an astonishing number of signs (21, in fact) warning divers and non-diving beachgoers that the steep slope of the sand connecting the land to sea causes frequent rogue waves strong enough to knock over even a large man and pull him into the surf.

“The waves come up from underneath and pull the pea-size gravel out from under your feet,” he explains, adding that he has seen experienced divers get pummeled by the waves, losing expensive gear (and a hefty dose of pride) in the process.

Wistfully, Ernst relates the story of a church group from Modesto who visited the beach in the spring of 2008. A 23-year-old woman and her father lost their lives trying to save a teenage girl who was struggling in the surf that day. A local man, clad in street clothes, saved the girl from what might have been yet another untimely death.

Still, for those who know the site well, the risk is worth the rewards. Visibility can extend up to 80 feet on a good day. Inflows of cold water bring in hundreds of brightly colored egg-yolk jellyfish (see photo) and nudibranchs. The canyon beckons technical divers who want to go deep, but still swim back to shore. Brilliant green kelp sways in the surge, creating a playground for lingcod and cabezon, who dart in and out, playing hide-and-go-seek with the wolf eels and octopuses.

Tips for the Monastery Diver

Regardless of skill level, all divers should follow these rules (courtesy of Harry “Doc” Wong, D.C., a well-known local technical diver who is also the President of the Northern California Oceans Foundation):

BEFORE THE DIVE:

- If you can, go with an instructor who will teach you how to dive the site.

- Dive only with people who know the site well.

- Read the forecast.

- Pick a day that has “ankle biter” sized waves. Pay attention to the transition from the steep beach to the deeper (safer) water.

- “Read” the number of divers on the beach.

- Know when to “call” the dive.

- Honestly assess your capabilities (and those of your dive buddies.)

- Consider a backup “octopus” (secondary regulator) on a necklace to ensure it stays in a location where you can get to it, even if you can’t see it.

- Talk to your buddy in advance to clarify your plan.

- Stay well away from the surf line until you are ready to go.

- Have an on-the-beach helper in place.

- Practice at the site with snorkeling gear—but no tank—before diving the site in earnest.

- After gaining experience, make an honest decision about whether or not you can safely and confidently dive this beach with your normal gear.

ENTERING:

- KEEP YOUR REGULATOR IN YOUR MOUTH AT ALL TIMES.

- Watch the surf line while getting ready to go.

- Choose the wave that you will enter by.

- After entry, get well beyond the surf line as fast as possible.

- If you are first to enter, keep an eye on the surf line while your buddy enters the water.

- If you fall, let go of your buddy’s hand and kick towards the ocean.

- Be prepared to help your buddy to deep water.

- Get heavy; dig in on the outflow.

- When crawling in, keep your fins flush on the sand so the waves can’t flip you heels over head.

- Keep your head low.

EXITING:

- KEEP YOUR REGULATOR IN YOUR MOUTH AT ALL TIMES.

- Synchronize your exit with the smaller waves. Let the inflow assist your return.

- When exiting, ensure that all gear is trimmed up so that you don’t crawl over it and get stuck.

- Make a fist and crawl on your knuckles. Crawl fast, and do not stop until you are at least 10 feet into the dry sand.

If you are on shore and you see someone struggling in the waves, do not attempt rescue. Call 911 immediately. Many well-intentioned people have died while attempting to assist others. Don’t allow the situation to become a double (or triple) tragedy.

About the Dive Site

The site has two “official names,” San Jose Creek Beach and Carmel River State Beach. Visit the beach’s official website (http://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=567) before making the trip. The weather can be changeable. Layered clothing is advised. Telephone number: 831-649-2836.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Writtren by Brianna Politzer Stevens, with photos By Jim Ernst

Brianna Politzer Stevens is a Bay Area journalist and PADI Divemaster who doesn’t dare dive Monastery. Jim Ernst, photographer and PADI-certified Scuba Instructor, is braver than the author, and has the photos to prove it.