It is cold here. The thin light somehow manages to support photosynthesis in the great kelps. The security of the underwater forest becomes a mere shadow far above me. Few of my peers know of this place. For a brief time, I escape the everyday concerns of that society, and visit another kind of existence. I am immersed in the universal solvent and movement is three dimensional. Nutrients bathe your body and sound travels four times faster than in our world. Pressures here are crushing but predictable; an environment which has little in common with the surface of the planet.

Words & Photos by Joe Dovala

It is difficult to describe my feeling of relief when the first strands of kelp come back into view. All vulnerability washes away once inside the undulating greenish brown curtain. Kelps as seen from underwater provide an amazing habitat which is hard to appreciate from a topside vantage point. The beach goer wrinkles their nose and scurries by the piles of giant brown algae unceremoniously dumped on the sand by waves. But just like the grandeur of a redwood forest cannot be gleaned from a truck loaded with chain-sawed logs, these odorous mounds of vegetation belie the vast riches and beauty of the kelp forest hidden beneath its canopy. Kelps love cold water and typically grow only along a very narrow belt within temperate seas. This includes the Northeast Coast of North America, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. By far the biggest concentration is off the Pacific Coast from Alaska through California into northern Baja California. Like a terrestrial forest, many ocean critters depend on these amazing stands of algae for food, shelter and as a nursery.

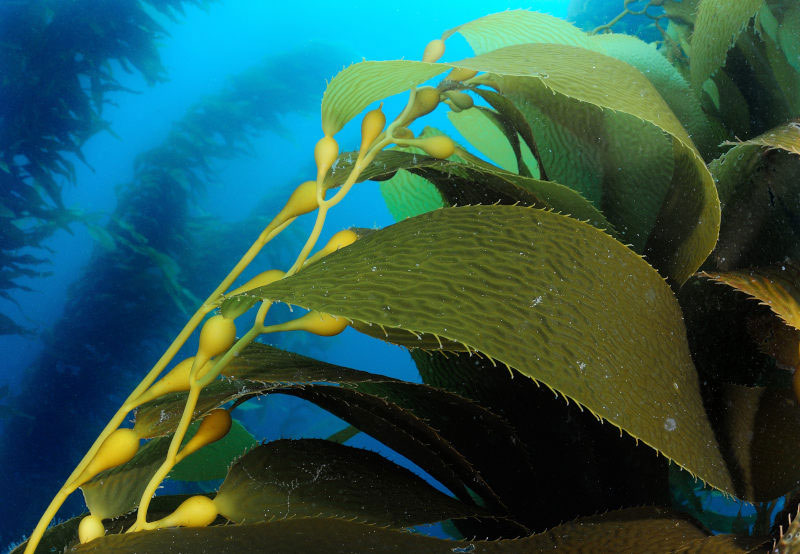

When baby kelps begin their life (reproduction is actually quite complicated), they start out as plankton; free floating, drifting with the currents until they find a suitable place for attachment where they can grow. These are usually rocks, but can be virtually any hard substrate including everything from automobile tires to ship wrecks. A structure called a holdfast forms and secures the young kelp to the bottom. The holdfast is often confused with a root structure but kelp is an alga – not a plant, and as such, does not have roots. It takes in nutrients throughout its structure, and gas filled floats called pneumatocysts buoy up the stipes and blades (analogous to branches and leaves in plants) toward the sun to allow for maximum photosynthesis. Kelp grows at phenomenal rates; nearly 2 feet per day under ideal conditions. While the holdfasts are tenacious, they can be broken loose by strong surges or from feeding activities of animals like sea urchins. Once the kelp loses its anchor, it begins to drift and can actually yank other kelps from their attachments. After winter storms the beaches can be wall-to-wall seaweed.

The holdfasts, stipes, and blades together create a living canopy that directly provides shelter and food for a number of animals. Blacksmith, a type of damselfish, are often seen in non-polarized schools in and under the kelp. Blue rockfish also spend much of their lives in the kelp canopy. Gobies, wrasses, greenlings, rays, flatfish, surf perch, and scores of other finned critters depend on the kelp stand.

Fishes inhabit more than mid-water under the canopy. A large number have made the bottom their preferred residence. The electric colored blue banded goby, also known as a neon goby, is a bottom dweller that can be found resting on their pectoral and ventral fins. They typically run ¾’s to just over 2 inches in length. Baby tree fish, a type of rockfish, are also very colorful and spend their early lives hiding in the shadows of crevices in the rocks. Kelp groves are routinely visited by transitory life too. Jack mackerel, harbor seals, sea lions, and even sharks make forays into the underwater jungle. Sometimes they look for food, sometimes to find cover, and once in awhile just to play amongst the swaying “vines” in the surge. Most kelp divers are well aware of the comfort the dense algal forest can provide against perceived open sea marauders.

Even when kelp brakes free and heads out to sea it can provide cover and food for marine life. Known as “kelp paddies,” these small islands of algae can float for hundreds of miles into deep ocean. Propelled by wind and currents, the kelp often has hitch hikers ranging from sardines to visits from whales. The wayward journey can go on for many weeks before the kelp deposits unceremoniously on some beach. Contrary to a plethora of very bad movies and television, kelp is very difficult to get seriously caught up in especially under the canopy. However, proper equipment configuration and techniques should be the norm when visiting an undersea forest.

A kelp community is much more than “seaweed and fish.” In fact, up to a thousand or more species may inhabit a healthy kelp bed stand. Besides the fishes and their young, it includes mollusks, crustaceans, anemones, gorgonians, bryozoans, sea stars, urchins, sponges, tunicates, annelida (worms), and the list could go on and on. Many of these critters actually live on the algae themselves. If you take a close look at a blade of kelp that’s been around awhile you’ll likely see small calcareous forms all over it – these are largely bryozoans. Many types of small anemones, hydroids, and mollusks also make homes on the stipes, blades, and holdfasts of kelp. Tiny mysid shrimp and scores of small fry dart to and fro between the protective blades looking for food. A healthy kelp stand is indeed a thriving forest.

Kelp is also more than a playground for divers too. For thousands of years humans have used kelp both directly and indirectly. It can be used promptly as a food or when processed can be made into a host of products. The big boom began during WWI when almost half-a-million tons were harvested to make potash for gunpowder and fertilizer. By the 1930’s a kelp component called algin found its way into all kinds of goods from frozen foods to toothpaste to vitamins. As an emulsifier, algin can keep ingredients in suspension for salad dressings, dairy products, and shampoos to name a few. Algin is also heavily used in scientific applications for research and development on a daily basis. Today thousands of wet tons are still harvested for a multitude of uses in cosmetics, paints, and animal feed. As we enter into the 21st century with the unknowns of global weather change, new pollutants, and invasive species, more pressures will most certainly come to bear on the sea’s forests. Hopefully, they’ll be able to adapt as they have for eons.

Words & Photos by Joe Dovala

Visit Joe’s website at DovalaPhotography.com