So, you want to dive on an iceberg?

Well, icebergs are beautiful. And they are exciting. And they are unique. But they also can be dangerous, even deadly. As we prepare to explore these beguiling wanderers of the sea, let’s examine the proper safety protocols and procedures for exploring icebergs under the water.

Diving on icebergs means diving in cold water!

But first, some basic information about these fascinating objects.

Icebergs come in all shapes and sizes. They are created when chunks of ice break off from the face of a glacier as it meets the end of its long journey on land and encounters the sea. Glaciers form on land when snow accumulates over thousands of years. As these layers compress, glacier ice begins to form, which then becomes rivers of frozen water that slide ever so slowly over the land seeking sea level. Of course, this means icebergs are usually formed in the polar regions of the Arctic and Antarctic, but they don’t necessarily stay there. Icebergs can drift north from Antarctica and south from the Arctic and cover long distances before they eventually melt in warmer waters.

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza & Christopher P. Weaver

If you explore along the face of a glacier, you will periodically hear the sounds of icebergs calving off and falling into the water. This sound resembles the crack of thunder and can be quite loud. Equally impressive is the sight of the iceberg dropping off the face of the glacier and crashing into the sea. Depending on the size of the ice chunk, massive temporary swells are created and these waves, along with the possibility of getting hit with ice is why it is dangerous to take your boat too close to the face of the glacier.

The dive team first scots potential icebergs to find one that is safe

Icebergs can be as small as chunks a few feet in size, to automobile size, to the size of a house or larger. Some icebergs are massive, with one recent iceberg measuring roughly the size of the state of Massachusetts.

Because of the relatively density of ice, which is made of fresh water, compared to the surrounding sea water, all icebergs float. And they drift. Roughly three quarters of the iceberg lies below the surface, which makes approaching an iceberg potentially dangerous for boats. Sharp protrusions and hidden ice blocks below the surface can damage a boat and quickly sink it.

Think Titanic.

Although icebergs float and drift at the mercy of ocean currents, they do occasionally “run aground” when they encounter water shallower than their maximum depth. Icebergs that are wedged on the ocean floor will cause an ice scour and may be grounded there for days or weeks or years. However, icebergs will usually last about three to six years, but this period could be shorter if they encounter warmer waters. Only when enough of the mass of the iceberg has melted, or when the ocean currents change direction, will an iceberg dislodge from the bottom.

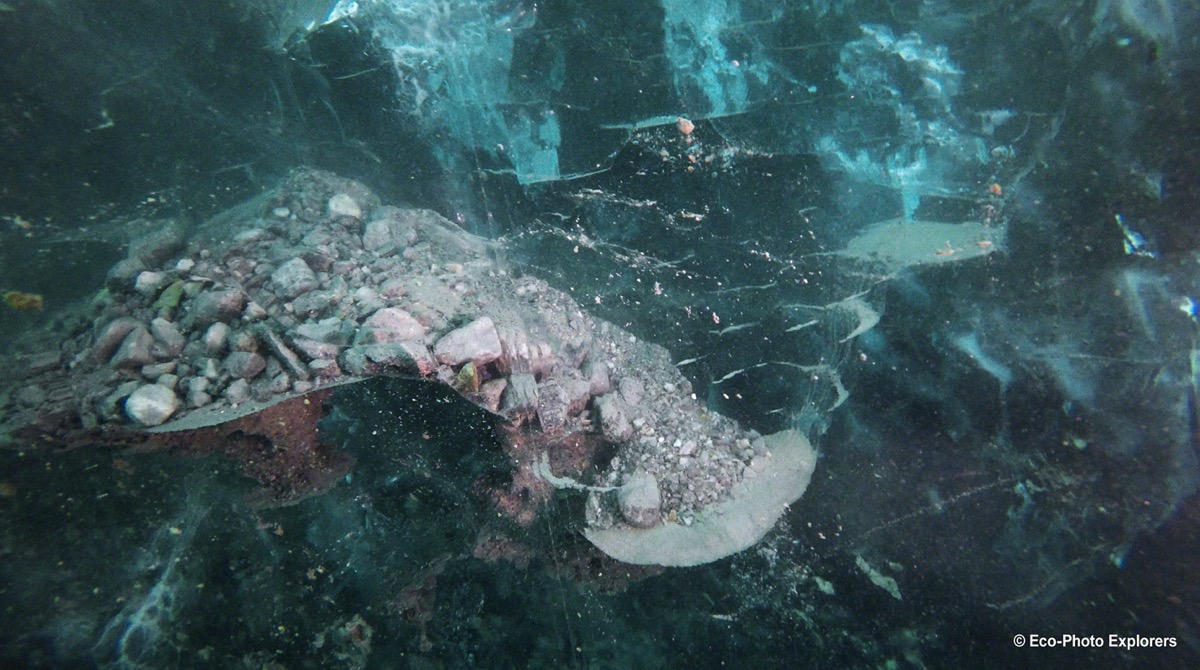

The translucent ice reveals the sediment trapped inside

Besides variations on shape and size, icebergs also come in different colors. Frozen fresh water is generally clear unless it is clouded with sediments. Through the millennia, the heavy pressure of ice weighing millions of tons crushes the ice closer to the bottom of the glacier and squeezes any dissolved air that may have existed in the ice. Icebergs that appear white are filled with air bubbles, much like an ice cube in your favorite drink. They appear white because these trapped air bubbles are scattering all wavelengths of light. But some icebergs sport a bright turquoise blue color, the color of pure glacier ice. This is the result of pressure compressing most of the air out of the deeper layers of ice which causes some ice crystals to absorb long wavelengths of light and at the same time reflect the blue colors of the light spectrum which is why we see blue. This ice is generally considered much older than white ice.

On very rare occasions, divers may encounter an iceberg that is a

Swimming alongside the crystal iceberg is an otherworldly experience

ctually transparent. This ice has been subject to extreme pressure and all the air has been pushed out, resulting in ice that resembles glass.

We explored one such iceberg on an expedition to Greenland.

It was early afternoon and the sun was peeking in and out of high clouds as we searched amongst the multitude of icebergs in the Rypefjord area of eastern Greenland looking for a stable iceberg to explore. After some time, we came across a fairly nondescript iceberg, one that almost had a dirty appearance on the surface as it seemed to have been stained with mixed rocks and soil on the jagged ice of the iceberg. It seemed stable and before long we were splashing into the water alongside this “dirty iceberg”.

The water was murky and it took a moment to focus our eyes as we searched for the underside of the iceberg. Slowly at first, and then more abruptly, the stunning image of this iceberg’s underside came into view. We were instantly captivated.

The crystal iceberg’s glassy ice reveals its interior

This particular glacial remnant drifting in the waters of Rypefjord emerged from the murky water as a crystal palace under water. The ice was clear as glass everywhere we looked! The transparent ice gave us amazing views into the inside of the iceberg itself. Trapped deep inside the crystalline glass were rocks, silt and dirt obviously caught in the glacier’s traverse across the Greenland landscape. There were shelves of glassy ice with piles of rock and stones resting on them as if they were part of an elaborate table setting, a time capsule freezing a period of time for future divers to gaze at in wonder. And, as the ice slowly melted in the surrounding salt water, waterfalls of silt could be seen cascading down the interior walls of the glass palace iceberg.

In some places, shards of glassy ice jutted out from the main body of the iceberg, and it was both beautiful and spooky to see the wavy images of divers on the other sides of these glass walls.

We had never seen anything remotely like this and we were mesmerized by the infinitely beautiful shapes and textures of this arctic wonder.

Have we piqued your interest?

Do you still want to dive on an iceberg?

The first step in diving on an iceberg is to find one that is relatively safe.

Icebergs are constantly melting. This is the reason for the safety protocols that are in place when diving on icebergs. The number one rule is to remember that because the iceberg is melting, it is inherently unstable. At any given moment, pieces of the iceberg can break off and fall into the water. Divers who are unfortunate enough to be under water where a chunk of ice has fallen can be struck by the block of ice and seriously injured.

None of these icebergs trapped in a cove in Greenland are safe to dive on

For this reason, icebergs that have protruding shelfs, overhangs, or jagged pieces of ice along their edges are not suitable for diving.

Icebergs that are towering in height are also off limits. These icebergs, which may appear more vertical in appearance, present real danger to divers. Since the iceberg is melting, its center of gravity could shift unexpectedly and without notice the entire iceberg will roll over, exposing its underside to the air. Divers who happen to be under an iceberg when such an event happens could become trapped in ice, seriously hurt by impact with the moving ice or crushed beneath the weight of the iceberg. If you spend enough time in a sea choked with icebergs, you will undoubtedly witness this roll over phenomenon, and you’ll get an idea how dangerous this can be.

The best candidate icebergs for diving are ones that are relatively flat or tabular, are of modest size and are not drifting close to shallow water. These are the ones less likely to roll over, less likely to calve apart and less likely to run aground.

Once a safe iceberg has been identified, to is time to prepare to dive. Naturally, diving on icebergs takes place in very cold water. Suitable or specialized ice diving regulators that are designed to operate in these extreme cold conditions and reduce the threat of free flowing, along with proper exposure protection, are absolute necessities. Dry suits are the norm.

A modest sized iceberg like this one makes for a safe dive

Divers should enter the water fairly close to the iceberg but not directly alongside of it. Entering the water a short distance away and then swimming to the iceberg reduces the risk of encountering submerged ice when you roll into the water. It also gives you a chance to adjust your gear and acclimate yourself to the conditions before approaching the iceberg.

Divers who approach the iceberg will notice that the nature of the water changes as you close in on the iceberg. Salt water changes to fresh water in the vicinity of the iceberg because all that ice is actively melting. Your vision will briefly become blurry as you encounter a halocline. Your buoyancy will change and as you draw closer you will begin to sink in the fresh water. Make sure you adjust your buoyancy with your BCD as this is happening and don’t allow yourself to begin sinking in an uncontrolled manner.

As you explore the iceberg, you will notice how smooth the submerged ice is. Running your hands along the ice will feel like you are touching Teflon. This is both beautiful and deceivingly dangerous. There is nothing to really hold onto and if you find yourself sinking, or drifting in a current, grabbing onto the ice may not be an option. It is critical that you are in control of your buoyancy and your movements.

The sides of an iceberg can be as smooth as Teflon

Sometimes the iceberg will have cracks and fissures under the water. Some divers may even encounter ice caves. While it is tempting to enter these caves, it is strictly forbidden to do so. Divers can get trapped in such a cave, especially if the ice shifts, compresses or the entire iceberg rolls while the diver is inside. Enjoy the iceberg from the outside and never venture inside.

Occasionally, divers exploring the underside of an iceberg may discover that it has actually run aground. Never explore close to where the iceberg is touching the bottom and retreat to open water and away from the underside of the iceberg immediately.

Finally, the end of your dive can be tricky. As with all dives, you should make a safety stop before surfacing but there will most likely not be an upline and the bottom may be very deep below you. As we mentioned earlier, buoyancy control near to the iceberg can become difficult to control. The safest place to do a safety stop is some distance away from the iceberg but perhaps within sight so it serves as a point of reference. Deploy your SMB if necessary, and make sure you don’t surface too early.

Always dive several feet away from the edge of the iceberg

From there, you will make your way back to the dive boat or RIB and exit the water. You may be heavier than normal so don’t hesitate to pass your gear to your surface support if necessary. Once on the boat, relax and realize that you have successfully explored an iceberg underwater.

Diving on icebergs can be incredibly beautiful and emotionally moving. The stunning vistas of the sides of a massive chunk of ice can be breathtaking. When conducted safely, dives on icebergs become lifelong memories. But always respect the iceberg and the danger it hides. All icebergs can be dangerous. Don’t gamble with your life by ignoring the safety rules of iceberg diving. The art of diving on an iceberg lies entirely on these safety precautions.

Now, let’s go find an iceberg to dive on.

Words & Photos by Michael Salvarezza & Christopher P. Weaver

- These icebergs have drifted close to shore

- This iceberg is a good candidate for a dive.

- Diving on icebergs means diving in cold water!

- The portion of the iceberg below the water can be seen in this photograph

- The sun sets on these icebergs in Greenland

- In Alaska we photographed this iceberg. Can you spot the reasons why this one is unsafe?

- From Alaska, this iceberg that recently rolled over shows an underside stained with dirt

- A mixture of blue glacial ice and dirty ice from the land comprises this iceberg in Alaska

- The dive team first scots potential icebergs to find one that is safe

- This large iceberg is too dangerous to dive on

- Click here to see video of the crystal iceberg

- None of these icebergs trapped in a cove in Greenland are safe to dive on

- This iceberg from Greenland is too large and potentially unstable to dive

- The crystal iceberg’s glassy ice reveals its interior

- Swimming alongside the crystal iceberg is an otherworldly experience

- A diver explores the crystal iceberg

- Inside the crystal iceberg were waterfalls of silt and sediment

- The translucent ice reveals the sediment trapped inside

- Always dive several feet away from the edge of the iceberg

- The sides of an iceberg can be as smooth as Teflon

- Polar diving can bring sudden changes in wind and weather. Divers must be prepared for shifts in the ice when diving on icebergs.

- These massive ice flows along the shoreline in Antarctica are not suitable for diving

- A modest sized iceberg like this one makes for a safe dive

- The prominent overhangs disqualify this iceberg

- Although these are tabular icebergs, this is an unsafe place to dive because there is no predictable open water.

- As tempting as this might look, never enter into tunnels, caves or cracks in icebergs

- This iceberg is top large, top-heavy and cracked to safely dive

- This glacier is tumbling to the sea in Greenland’s Scorsbysund region