A school of Bluestriped Grunts photographed in Marathon

Text and Photography by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher Weaver (Eco-Photo Explorers)

Stretching from Martin County on the Atlantic Coast to the Dry Tortugas, the coral reef system off Florida’s coast is quite extensive. Ever since the advent of SCUBA diving, these reefs have held a special place in diver’s minds and logbooks. Brilliantly colored coral reefs teeming with fish life became the stuff of legends. And with easy access to the mainland via an overseas highway, choosing to dive the Florida Keys was a no-brainer.

If we’re being honest, though, the situation today is not the quite the same. The corals in the Florida Keys have taken a beating and the reefs have degraded badly. In many areas, once healthy and thriving reefs are now mere relics covered with algae. NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program annual report in 2020 rated the reefs as “impaired”, with the corals suffering from the impacts of climate change, ocean acidification, overfishing, rapid population growth and coral disease. For example, an ongoing outbreak of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease has spread through the extent of the reef system and affects 45% of the species of corals in this area.

Some scientists consider the situation “dire”, and estimates are that only 2% of the coral cover remains healthy on these reefs.

With that seemingly terrible news, is a dive trip to the Florida Keys worth it? In a word, “Yes!”.

Besides the reefs, which still support large populations of fish, there are shipwrecks throughout the keys which serve as great diving alternatives to the battered reefs. These wrecks, many of which have been intentionally sunk as part of Florida’s Artificial Reef program, all have intriguing histories and make for entertaining dives. Some are challenging for the advanced divers and others are more accessible for newer divers. All serve to relieve the diving pressure on the reefs while continuing to fuel the local economy through diver visits.

Our adventure started in Key Largo with a dive to the wreck of the USS Spiegel Grove.

USS Spiegel Grove (LSD-32) was a United States Navy Thomaston-class dock landing ship named for Spiegel Grove, the home and estate in Fremont, Ohio of Rutherford B. Hayes. She was launched on November 10, 1955. Her service career brought her to the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, Europe, the Middle East, Africa and beyond, including operations to support Scott Carpenter’s manned space flight in Mercury-Atlas 7.

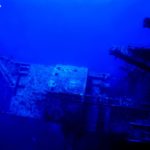

A ghostly view from the Spiegel Grove

She was decommissioned in 1989 and was given to the state of Florida in 1998 to be sunk as an artificial reef. On May 17, 2002, she sank upside down prematurely on the Dixie Shoals off Key Largo. Several weeks later, salvage crews managed to turn the wreck onto her side and within a week, 1000 divers visited the brand-new wreck. Those early divers were fortunate to see the wreck lying on her starboard side because three years later, hurricane Dennis shifted the entire wreck onto her keel, right side up, as she was originally intended to be sunk!

As we descended the down line on one of the many mooring balls on the wreck, the enormity of the ship became apparent in the clear 80 degree water. Measuring 510 feet in length and sitting in 130 feet of water, the wreck disappears off the edges of visibility, a ghostly structure beckoning diver to wander beyond their abilities. With strong currents and deep water, divers should have advanced certification to explore this wreck. A dive guide is a good idea for first time Spiegel divers.

Author Mike Salvarezza explores the Spiegel Grove in its early days as an artificial reef

We hit the deck around 90 feet, and quickly made our way to the bow. Once there, we turned back and began to explore the bridge area, enjoying some of the swim throughs and opportunities for penetration. At about mid-ships, a large crane rests along the deck and it was here that we made our way back to the surface. The Spiegel Grove was, at the time of its sinking, the largest intentionally sunk ship in the world. That “record” has since been eclipsed, but nonetheless she is a large shipwreck that requires several dives to fully explore.

There are other wrecks off the shores of Key Largo, including the twin US Coast Guard Cutters Bibb and Duane. The Duane was Commissioned Aug. 1, 1936, and was named for William John Duane, the third Secretary of the Treasury, who served under Andrew Jackson. Her service included escort and patrol duty in the North Atlantic and the Pacific, along with support missions off the coast of Vietnam, operations during Cuba’s Mariel Boat Lift in 1980 and a plethora of drug busts in warm Caribbean and coastal waters during the 1980s.

Duane’s sister cutter, the George M. Bibb, was named for George Motier Bibb, Secretary of the Treasury from 1844-45 under President John Tyler. She served on active duty for nearly 50 years, from 1936 to 1985 and participated in patrol duties during World War II in such ports as Pearl Harbor, Guam and Singapore, along with peacetime jobs of search and rescue, and logistical support for the U.S. Navy.

Both the Bibb and Duane were sunk within a day, and very nearby, of each other on November 27-28, 1987 one mile south of Molasses reef in 130 feet of water. These two ships are now on final duty resting alongside of each other and both make for fascinating dives.

John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park is popular with divers and snorkelers

Key Largo is home to the John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, a 70 nautical mile preserve featuring some interesting dive sites. Perhaps the most iconic is the Christ of the Abyss statue, an 81⁄2-foot-tall statue of Jesus Christ weighing 4,000 pounds standing in nearly 25 feet of water. First placed here in 1965, it is a popular site for snorkelers and divers and before we left for points south we wanted to check this one off our list. Swimming around the statue with the sun’s rays streaming down from the surface created an ethereal feel to the dive site.

Our next stop on our journey would be Marathon, where we had hoped to dive the wreck of the Thunderbolt.

The Thunderbolt was built by Marietta Manufacturing Company at Point Pleasant, West Virginia, under contract to the U.S. Army during World War II. Originally named Randolph, she was launched on June 2, 1942 and was built to plant and service defensive coastal minefields for the Army’s Coast Artillery Corps. In 1949, the Randolph was transferred to the Navy.

Caribbean Enterprises of Miami purchased the vessel from the Navy in 1961 and subsequently, Florida Power and Light bought her to do research on the electrical energy in lightning strikes. This led to her new name, Thunderbolt. Eventually, Florida Power and Light donated the ship to the Florida Keys Artificial Reef Association. On March 6, 1986, she was intentionally sunk in 120 feet of water four miles south of Marathon as part of the Florida Keys Artificial Reef Association project. We were hoping for the opportunity to create some images of the wreck as she sits upright on a sandy bottom but, alas, this was not to be! A recent winter storm had torn the mooring buoy off the wreck and the local charter boats were unable to visit her while we were there. Nobody ever said diving is predictable!

A mixed school of Schoolmaster, Bluestriped grunt and French Grunt in Key West

As an alternative, we made our way out to Sombrero Reef and explored some of the shallow waters alongside the Sombrero Reef Lighthouse. Here we found healthy schools of snapper, grunt and porkfish, along with the usual butterflyfish and an occasional French Angelfish. The reef structure here is in a tongue and groove pattern, with the depth of the water never reaching beyond 40 feet. It’s fairly straight forward to navigate as you traverse up and down the fingers of the reef in this area. Its best to keep some distance from the lighthouse itself as the water gets very shallow close to the structure.

After we left Marathon, we headed for Big Pine Key, about 30 minutes from Key West. Although the wreck of the Adolphus Busch gets a lot of attention here, visibility is often marginal on the wreck. We opted to explore Looe Key instead, hoping to see some of the healthiest corals in the region.

Looe Key is a Sanctuary Protected Area within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Mooring buoys are placed throughout the reef to enable boats to “tie up” without damaging the fragile corals of the reef. The water is very clear and shallow here and our dives never exceeded 30 feet of depth. Although a lot of attention is paid to buoyancy control and other measures to protect the reef, the sheer number of boats dropping off divers and snorkelers was concerning. Still, we found the reefs to be healthy here, with large aggregations of snapper and grunts along with barracuda, angelfish and other common reef fish. In one sandy patch we came across a 6-foot Nurse Shark resting quietly on the bottom. We also spotted the ever attentive spiny lobster poking their antennae out of various coral holes as we swam over the reef.

A Nurse Shark from Marathon

Key West was the last stop on our journey. Clearly, Key West is more of a party town than some of the other islands in the keys, but offshore from the pulsing social life of Duval Street in the solitude of the warm waters of the Atlantic are two spectacular wrecks for divers to visit.

Lying seven miles southeast of Key West, the Cayman Salvager is one of Florida’s great wreck dive sites. Because of the popularity of the Key West’s Vandenburg shipwreck, the Cayman Salvager doesn’t get as much attention but we found the wreck to be a terrific one to explore.

The ship was built in 1937 and was used as a buoy tender by the Coast Guard as well as a cable layer, a mine planter, and a freighter. The history of the ship becomes a bit murkier after this, but what is known is that in 1980, while illegally transporting Cubans during the Mariel boatlift, the Cayman Salvager was seized by US Government authorities and was towed to Key West where she unexpectedly sank while at dock.

Five years later, in 1985, plans were made to raise the ship and re-sink her as an artificial reef. She was being towed to the planned location in deep water when her tow-rope snapped and she sank where she now rests, in 90 feet of water.

Over the years, hurricanes have alternately pushed the ship onto her side and then righted her again. Today, the wreck is upright and has some interesting things to explore, including three bicycles, a payphone and a cable spool and pulley on the bow.

We were able to explore the entirety of the 187-foot shipwreck on our dive. The ship’s superstructure is all gone and the most interesting penetration opportunities are when dropping into the large cargo holds below decks.

The ship’s stern sits in 92 feet of water, its engine room and interior compartments are located at 80 feet and open decks can be found at 70 feet. The wreck is close to the currents of the Gulf Stream, which means that divers can usually expect excellent visibility, although that is never guaranteed.

The final dive of our Florida Keys expedition would be on the wreck of the USNS Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg.

The Vandenberg was built in 1943 by Kaiser Shipyard in California and was originally named the USS Gen Harry Taylor. She was commissioned as a troop transporter, carrying personal during the last years of WWII and was the first ship to return to New York Harbor after the surrender of Japan.

The main deck of the Vandenberg

The Vandenberg (then the USS Gen Harry Taylor) remained in service until 1958 when she was decommissioned for the first time. But in 1961 the ship was acquired by the Air Force and re-commissioned, this time as USAF’s Gen Hoyt Vandenberg and she was used as a missile tracking ship. In 1983 she was re-acquired by the Navy and continued to serve as a missile tracking ship until she was retired for good in 1983. Eventually, plans were made to turn her over to the state of Florida for sinking as part of the state’s artificial reef program. But the Vandenberg had one more mission to accomplish.

Prior to her intentional sinking by Florida, she was featured in a Hollywood movie. In 1998, some of the scenes of the film “Virus”, starring Jaime Lee Curtis, William Baldwin and Donald Sutherland, were filmed aboard the vessel, which had been christened to be the Russian vessel Akademik Vladislav Volkov for the movie. “Virus” has disappeared into the realm of DVDs and streaming services, but the Vandenberg, which was sunk on May 27, 2009, is now enjoying fame as a world class dive site.

Open hatch from the Vandenberg wreck in Key West

As with all the other Florida artificial reef shipwrecks, several mooring balls are permanently installed on the wreck, making ascent and descent easy. The wreck sits upright in 140 feet of water but is reachable in about 80 feet of water. With almost 80 foot visibility and no current on our dives, we were able to explore the entire length of the 522 foot vessel. Much of the ship’s superstructure remains, and large holes have been cut to provide for easy penetrations. The ship’s radar domes were left on the vessel when she was put to the bottom, but these spider-web shaped structures are falling apart quickly. Still, they make for good images and excellent landmarks.

After several dives on the Vandenberg, it was time to draw our journey to a close. There are many more shipwrecks to explore and more reefs to survey and we will save those for another time.

The Florida Keys are certainly one of America’s natural treasures. Divers have long known the beauty, and the fragility, of the coral reefs here. Over the years, we have watched as the corals have begun to die. There are many reasons for this, almost all of them man-made. Sadly, the reefs today are only a shadow of their once former glory. As divers, we now have shipwrecks here to satiate our thirst for underwater adventure. And we continue to dive the reefs, catching glimpses of the majesty of the ecosystem with a passing school of snapper or in the baleful gaze of a barracuda. We encourage divers to visit the keys and to experience the wrecks and the reefs.

It is through our eyes, the lenses of our cameras, and the words of our stories, that we can tell the world how valuable this place is. And how much we need to do to help protect it.

Text and Photography by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher Weaver (Eco-Photo Explorers)

- An open hatchway on the wreck of the Vandenberg

- Three years after she sank, Hurricane Dennis flipped the ship upright onto its keel

- The crumbling remains of a radar dish from the Vandenberg

- Divers explore the wreck of the Cayman Salvager in Key West

- A ghostly view from the Spiegel Grove

- The Spiegel Grove originally lay on its side

- The Spiegel Grove prior to its shift to an upright position

- Author Mike Salvarezza explores the Spiegel Grove in its early days as an artificial reef

- The Spiegel Grove is a photogenic wreck

- A Spotfin Butterflyfish poking around the reef at Looe Key

- Porkfish swim in large schools over the reefs

- The Vandenberg is a massive wreck with plenty to explore

- Deck rails from the Vandenberg

- The Christ of the Abyss statue makes for a spiritual dive site

- Open hatch from the Vandenberg wreck in Key West

- : The Sombrero Reef Lighthouse marks a good dive site

- The remains of a radar dish are covered with marine growth

- A school of Bluestriped Grunts photographed in Marathon

- Inside the Spiegel Grove long before it was covered with marine growth

- A mixed school of Schoolmaster, Bluestriped grunt and French Grunt in Key West

- The Florida Keys is home to large schools of reef fish

- The main deck of the Vandenberg

- Shipwrecks in the Florida Keys are home to a variety of fish, like these Gray Snapper

- A Nurse Shark from Marathon

- An open hatchway beckons

- A snorkeler swims over the Christ of the Abyss statue

- The Florida Keys have a unique vibe

- John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park is popular with divers and snorkelers

- The Vandenberg is now completely covered with colorful marine growth