The History

The American Revolutionary War defined the beginnings of an independent United States and it was a struggle of historic proportions both on land and on sea. Throughout the colonies in North America, battles were fought and lives were lost. Long Island, New York, is home to numerous sites central to the fight for independence. The Battle of Brooklyn, the attack on Fort Slongo and the Culper Spy Ring are all examples of how Long Island meaningfully affected the war.

The fight for independence on Long Island extended to its surrounding waters.

In early July 1780, a French fleet of 13 frigates and 7 “ships-of-the-line” arrived into the harbor at Newport, Rhode Island. Ships that were equipped to fight in the line of battle were referred to as “Ships-of-the-line”. This was an attempt to assist the American Patriot army in their battle with the British by supplying ships, artillery and 6000 troops.

By September 1780, 14 British warships, including the HMS Culloden, arrived on Long Island to provide reinforcements to a small fleet in Gardiner’s Bay and by October the HMS Culloden was stationed in Gardiner’s Bay. The Culloden, along with three other vessels, were instructed to patrol the area between Montauk Pt. and the Nantucket Shoals, and to defend against any French ships trying to enter this area. Essentially, they had formed a blockade.

The HMS Culloden had been launched on May 18th, 1776 with a gun deck measuring 170 feet. She was designed to carry 74 guns and had a crew of 650 officers and workers. Captain George Balfour was selected by the British Lords to command the vessel.

The first years of her service found the HMS Culloden operating off Cape Finisterre, Spain, preying upon enemy munition ships bound for the American Colonies, and the British coast where she was ordered to intercept and destroy all merchant vessels found to be trading with France, an enemy country because she was engaged in assisting the American Colonialists. She also saw action off Gibraltar, Mauritius and the Caribbean island of St. Christopher (now referred to as St. Kitts), before being sent to North America to participate in fighting the revolting Colonialists.

On January 20, 1781, word was received that the French were preparing to leave Newport and were going to run through the blockade. The HMS Culloden, and two other vessels immediately set sail from Block Island Sound in pursuit of the French vessels.

On January 23, a strong winter storm rose up and the ships became lost and disoriented in the severe weather and blinding snow. Mountainous seas were battering the vessel as she tried in vain to sail her way through the tempest towards Rhode Island. It was one of the ship’s lookouts that shouted over the gale that land was close by but it was too late. The mighty HMS Culloden struck bottom and had run aground.

In the dark of night, the crew could barely make out the shoreline but they were convinced that they had hit the shores of Block Island. At daybreak on January 24, though, they realized they were actually offshore of a place known as Will’s Point on the south shore of Fort Pond Bay in Montauk, Long Island. The ship was only a short distance from Gardiner’s Bay and had been blown back from its forward progress during the storm.

Text and Photography by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher Weaver (Eco-Photo Explorers)

Efforts were organized to free the vessel from the grip of the sea bottom but to no avail. Captain Balfour then ordered all valuable material removed from the ship. The Culloden was extensively salvaged over a period of weeks before finally coming to rest in 15-18 feet of water just a few hundred feet offshore.

The other two ships that left Gardiner’s Bay to meet the French threat fared only marginally better. The Bedford was heavily damaged and de-masted while the America was blown far off course and ended up off the Virginia Capes, taking almost two weeks to return to the area after the storm. The French fleet made out much better because they had the good fortune of turning back and returning to port before the storm could damage their vessels.

Captain Balfour was eventually tried in a court-martial proceeding for the loss of the Culloden and was eventually honorably acquitted. Will’s Point was subsequently renamed Culloden Point. After the conclusion of the war, the story of the HMS Culloden disappeared into the pages of history.

Diving the Wreck

The remains of this historic shipwreck have been lying in the shifting sands of Fort Pond Bay for over 200 years, often completely buried, and sometimes with just a few timbers exposed to indicate the wreck site.

Divers who wish to explore the wreck find that, although shallow, it is a difficult wreck to locate. Despite this, the wreck of the HMS Culloden remains one of Long Island’s premier dive targets.

The dive is a shore dive and in years past the first obstacle to diving the wreck was to access the shore from a steep bluff overlooking the beach. Intrepid divers would lower equipment on ropes and rappel the sheer bluff wall just to get to the shore. Because of safety concerns, a straight staircase was constructed that enabled divers to easily reach the beach, but it was destroyed over the years due to storms and hurricanes. Unfortunately, divers had to once again return to rappelling the sheer bluff wall.

Today, divers once again can safely access the beach by using a new multi-level staircase that includes a landing halfway down, which gives divers a place to rest or stage gear. The replacement staircase was installed in the summer season of 2019 by the town of East Hampton and a local diver’s advocacy group known as the Long Island Diver’s Association (LIDA).

Once on the site, divers need to locate a large boulder at the water line and take a compass heading of 330 degrees from there to find the wreck, which lies about 150 feet (46m) from shore. The shoreline here is littered with seaweed covered rocks and boulders, and scrambling over these stones in very shallow water in full dive gear is not only strenuous but also treacherous. Divers need to exercise great care before getting to water deep enough to begin the dive. Some divers have referred to this as “walking over wet bowling balls.” It’s best to dive this location at high tide.

Once underway, divers descend along a gradual sloping bottom until they reach a depth of 15-18 feet, depending on the tide. The water here can be clear or very murky, depending on the prevailing wave action. The gale that sank the Culloden is evidence of how strong the wave action can be in this area. Visibility can range from a few inches to 20 feet.

The wreck itself is very low-lying and often completely covered in sand. On occasion, only a few timbers will emerge from the shifting sands. But sometimes after significant storms, the entire outline of the wreck can be found. Careful observations will reveal the shape of the ship as divers swim over the decomposing wood of the Culloden. Even during these times, the exposed portions of the wreck rarely rise more than a few inches out of the sand. With visibility often measured in single digits, a small deviation from the compass heading can cause a diver to miss the site completely.

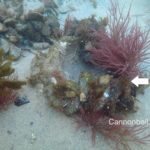

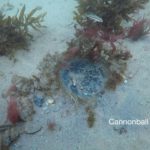

It takes a keen eye to spot some of the other interesting artifacts of this historic wreck. Lying on the north side of the wreckage are five cannons, each with the main body of the weapon pointing down and buried in the sand. The exposed piece, known as the cascable, is almost indistinguishable from a seaweed covered rock but the distinctive knob serves as a positive identifier for the trained eye. Also, sharp-eyed divers can spot cannonball imprints alongside the wreckage and while examining these unmistakable indentations in the bottom it’s easy to imagine the fury of the battle when this ship was in service over two centuries ago.

On one of our dives, we came across remnants of copper sheathing, which was used to protect the wooden sides of the vessel, after a strong storm had disturbed the site. The wreck of the Culloden is a protected site and is on the National Register of Historic Places. This makes it illegal to remove anything from the wreck and so we left the tantalizing artifact where it lay. This protected dive location is the first underwater park in Long Island, New York.

The waters of Fort Pond Bay are heavily used by recreational boaters and fishermen. Personal watercraft can also zoom by on summer days so a diver’s flag is a necessity and required to dive this site safely.

The final resting place of the HMS Culloden sounds like an easy dive: a wreck lying in just 15-18 feet of water off the shore can’t present too many problems, can it? Well, the difficult shore entry, the sometimes marginal visibility and the elusiveness of the wreck itself in the shifting sands all combine to make this a greater challenge than it would appear. But the challenge is worth it. The HMS Culloden is an historic wreck which connects us all to a time more than two centuries ago when the British and the upstart Americans were engaged in a war that would eventually change the world.

Text and Photography by Michael Salvarezza and Christopher Weaver (Eco-Photo Explorers)

- Divers rappelling the bluff before the staircase was built (photo courtesy Robert Auteri)

- In years past, divers had to lower gear down a precipitous bluff to access the site (photo courtesy Robert Auteri)

- The divers pause for a portrait while exploring the wreck

- Author Christopher Weaver photographs the wreck

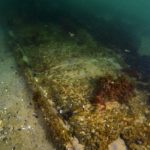

- Most of the wreck lies below the sand.

- The exposed portion of the hull is overgrown with marine life

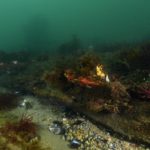

- Divers explore the Culloden hull

- The decaying remains of the Culloden’s hull

- The cascable is the visible portion of the cannon

- Cannon embedded in the sand

- Spiral egg case of a Channeled Whelk

- Clearnose Skate on the seabed near the wreck

- The dive team at the trail entrance

- The location of the wreck site

- Copper sheathing found on the wreck site

- Entrance to the short walking trail to the wreck site

- Author Michael Salvarezza points to the wreck location

- The HMS Culloden wrecked just offshore of this beach

- A short trail through the woods leads to the staircase

- Large boulder on the shore is the main landmark

- Staircase installed by the East Hampton Town and Long Island Divers Association

- Culloden Point has a rocky shoreline

- Diver searching for the wreck

- A Rosette Skate in the sand near the wreck

- Cannonballs left these imprints on the wreck

- Cannonballs left these imprints on the wreck

- Cannonballs left these imprints on the wreck

- Cannonballs left these imprints on the wreck

- Three cannon on the seabed

- Three cannon on the seabed

- A diver explores one of the Culloden’s remaining cannon

- A diver explores one of the Culloden’s remaining cannon